Space Archaeology

NASA satellite imaging

In late May, 2011, news reports began to circulate describing how images of lost, undiscovered or misunderstood archaeological sites in Egypt were being

identified using remote sensing imaging data from both NASA and commercial satellites,

orbiting some 700kms, (or 435 miles), above the Earth.

By directing infrared light, visible light, microwave and thermal imaging devices at the Earth and capturing resultant data with a range of cameras and other receptors,

buried sites, not visible on the surface,

come to life for archaeologists to study, governments to administer and security guards to protect.

Thanks to NASA and others we now have an enhanced Space Archaeology satellite imaging technological capability to accurately identify and map buried archaeological settlements, across large areas. Objects or features of less than a metre in size

can be discerned.

Through trial and error in relation to satellite imaging of the Egyptian terrain, Dr. Sarah Parcak, who has done much to pioneer these techniques,

discovered that the most informative images were taken during the relatively wet weeks of late winter. During this period, buried mud brick walls absorbed

more moisture than usual, producing a subtle thermal signature in the overlying soil that showed up in high-resolution, infrared satellite images. These places became “our hot spots, the places

that we could end up exploring on foot,” she says.

As everyone knows, different things are different temperatures in the same setting, which is why an asphalt road is far hotter than grass on a summer day. Similarly, things buried underground have different temperatures, too. It is these different heat signatures that allow infrared archaeology to be possible as, when shot at the right wavelength, traces of buried ruins will appear on the ground because the soil (or in this case, sand) directly above them is of slightly different temperature than the sand that covers nothing at all.

In Egypt, the very building materials used by the ancients, mud brick and stone, are especially suited to giving off a distinct heat signature when imaged in the infrared. However, infrared imaging can also differentiate between compacted soil used in Earthworks and regular dirt.

"What these satellites do is they record light radiation that's reflected off the surface of the Earth in different parts of the light spectrum," Parcak explains. "We use false color imaging to

try to tease out these very subtle differences on the ground."

Those subtle differences are an archaeologist's clues to what might lie under a rice paddy or a city street. "You just pull back for hundreds of miles using the satellite imagery, and all of a sudden

this invisible world become visible," Parcak says. "You're actually able to see settlements and tombs — and even things like buried pyramids — that you might not otherwise be able to see."

As of May, 2011, it seems that, in relation to Egypt alone, 17 new 'possible' pyramids, 1,000 new tombs, and 3,000 new sites

in total have been identified.

This Space Archaeology satellite imaging technology could mean that we now have an enhanced potential to monitor, assess and protect

archaeology from space, with high precision

Parcak received her Bachelor’s degree in Egyptology and Archaeological Studies from Yale University in 2001. From 2003 to 2004,as a graduate student, Parcak used a combination of satellite imaging analysis and surface surveys in the detection of 132 new archaeological sites, some

dating back to 3,000 B.C and worked on her dissertation on satellite imaging at the University of Cambridge.

(Parcak said the idea to harness satellite technology came from her grandfather, a forestry professor who pioneered the use of aerial photography in his field.)

She searched scientific papers in geology

and other fields for information on how to analyze satellite images; there was then no definitive textbook for remote sensing satellite

imaging space archaeology.

While still in graduate school the potential

of her approach soon began to become excitingly evident.

Parcak loaded an image of the Egyptian Nile River Delta taken by NASA’s Landsat Earth-observing satellite into a program called Erdas Imagine, a cross

between Google Earth and Photoshop that geologists and climate scientists use to analyze satellite images. All natural features—trees, water, sand—reflect and absorb light differently, and the

program can tease out any unique signature the researcher is looking for. Using data from known archaeological sites, Parcak had already figured out how to sort for the high organic matter

and phosphorus content that marked Egyptian “tells,” or ancient house mounds. She processed the new images so that any tells would show up pink.

When she analyzed the images, her computer screen filled with pink splotches. “I thought, ‘Wait a minute, those can’t all be archaeological sites,’ ” Parcak recalls. But then she went into

the field with a GPS receiver. At the pink points on the Landsat image, the delta’s flat green fields gave way to silty brown mounds: remnants of tells. Parcak has since used satellite

data to uncover hundreds of sites in Egypt, none of them exposed to the naked eye.

As initial techniques of such remote sensing have become refined upon it has been established that by detecting differential changes in material densities and heat stored within buried

archaeological features, and comparing that with the background response of surrounding natural sediments

or geology; the footprints or outline of archaeology no longer visible in the modern landscape can be seen.

For example, the hard mud brick that Egyptian houses were normally constructed from give a different signal or response, under certain types of

infra-red imaging exposure, to the loose desert sand sediments surrounding it.

As of 2011 NASA’s Aster satellite images the Earth in 15 different wavelengths. Sarah Parcak and others process the data using techniques that show fields as red, cities as blue and ancient ruins green.

NASA/JPL/University of Sydney

A zoomed-in view of the image reveals a subtle green mound among the red fields. The white square is a water-treatment plant

NASA/JPL/University of Sydney

Using a visible-light image from the Quickbird satellite, Parcak spots a buried wall

[stretching from the center of the brown field toward the upper left].

Sarah Parcak/University of Alabama

An on-the-ground dig identifies the ruins as the enclosure wall of the ancient city of Tell Tebilla, which dates from 600 B.C.

Sarah Parcak/University of Alabama

Thanks to these newly emergent satellite imaging techniques in Space Archaeology, NASA, Dr Sarah Parcak of the University of Alabama, and many others are changing the historical concept of settlement, and burial practises, in Egypt. Large areas of land can be

investigated using satellite remote sensing, allowing archaeologists to get a better sense of spatial distribution, size, scale, complexity… and discover unknown sites.

The infrared images are able to detect those remains in the first metres of the earth’s surface, in areas where there is no modern development. Parcak suggests that there may be

more sites and monuments at deeper levels still unknown.

The breakthrough find is a huge coup for the burgeoning science of space archaeology, but Parcak believes this is only the beginning, even hinting further finds could be buried deep below the Nile River.

"These are just the sites close to the surface," she told the BBC. "There are many thousands of additional sites that the Nile has covered with silt."

Yet Parcak’s technique is not universally applicable; what works in the Egyptian delta won’t necessarily work in the Brazilian rainforest. Archaeologists have to tailor remote sensing to their

sites. Satellite imagery is valuable for wet agricultural regions like the delta or heavily forested areas, while treeless plains or deserts call for radar.

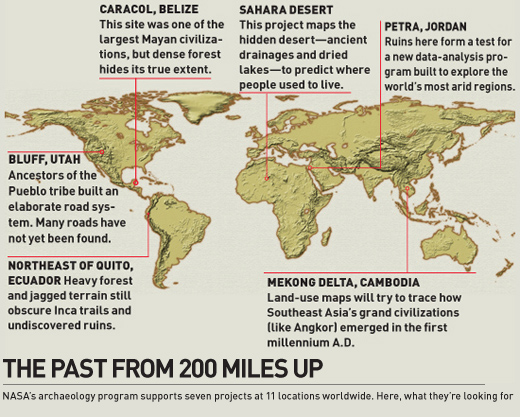

NASA supports a defined programme of Space Archaeology related satellite imaging. It recognises a number of regions across the globe as being

of particular interest.

Such space archaeolgy has been attempted before, however. Satellite imaging and radar technology were used by Damian Evans and Bill Saturno from the University of Sydney to visualise the Angkor Wat complex in 2008 from 200

miles in the air.

|

|

![[space archaeology NASA]](archaeologist.gif)

![[space archaeology NASA]](archaeologist.gif)