![[german revolution 1848]](../../enlightenment.gif)

German National Assembly, Germany, german revolution 1848

Frankfurt Vorparlament, Prussia, March Days![[german revolution 1848]](../../enlightenment.gif) German National Assembly, Germany, german revolution 1848 |

| Home > History & Historians > 1848 > Germany revolution 1848 |

|

|

In these times in the diverse states of the Germanies several rulers were faced with respectful, yet determined, demands for change and, starting with Baden in early March, moved to award Constitutions or to allow liberalisation of existing Constitutions. The powerful north german Kingdom of Prussia was then ruled by King Frederick William IV who was determindly anti-liberal in outlook. During the inaugurating ceremonies to an 'United Diet' of his territories that had been called in the spring of 1847 in order to gain formal consent for the raising of new taxes and the raising of a state loan in relation to unprecedented spending on railway construction, (and was the first such assembly of representatives from all the provinces of Prussia that any Prussian monarch had been prepared to recognise), King Frederick William IV had said that:- "There is no power on earth that can succeed in making me transform the natural relationship between prince and people ... into a constitutional relationship, and I never will permit a written sheet of paper to come between our God in heaven and this land ... to rule us with its paragraphs and supplant the old, sacred loyalty." In the closing sections of this inaugural address Frederick William that the United Diet would only be reconvened if it showed itself to be "good and useful, and if this Diet offers me proof that I can do so without injuring the rights of the crown." The turbulences of 1848, however, spread to Berlin and after an incident precipitated street fighting the King withdrew his soldiers rather than see even more fatalities amongst his "beloved Berliners" and was subsequently called upon by the populace on the 19th to stand bareheaded whilst the earthly remains of those Berliners killed in the street fighting were paraded with their wounds exposed. The King formalised a change in political direction through the appointment of a new ministry and proclamation issued on the morning of the 21st offered official recognition to the emergence of a single German nation. announced that the King had placed himself at the head of the movement for the redemption of Germany and would appear on horseback that day in his capital wearing the "venerable colours of the German Nation".

These black, red, and gold, colours were at one and the same time "revolutionary" in being associated with contemporary German Liberalism and Nationalism having been adopted by "patriotic" students in 1817 who were opposed to the official German Confederal repression of liberalism and "German-patriotism" in these early years following the overthrow of Napoleon but were also thought of as being associated with the earlier "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation," (which had been discontinued as a result of a dramatic reorganisation of the Germanies that had been sponsored by Napoleon at thre height of his power). The students of 1817 may themselves have been influenced in their choice of emblem by the example of the Lutzow Freikorps - a semi regular force that featured many students and intellectuals in its ranks - that had played a celebrated role in the then recent "Wars of Liberation" against Napoleon. During his progess through the streets of Berlin the King was occasionally hailed as Emperor but he felt moved to assert that he intended to rob no German prince of his sovereignty. A Declaration entitled "To My People and to the German Nation" was issued towards evening which sought to sum up up the position being adopted:- "Germany is in ferment within, and exposed from without to danger from more than one side. Deliverance from this danger can come only from the most intimate union of the German princes and people under a single leadership... I have taken this leadership upon me for the hour of peril... I have today assumed the old German colours, and placed Myself and My people under the venerable banner of the German Empire. Prussia henceforth is merged into Germany." The Federal Diet of the German Confederation declared on 8 March that a revision of the Constitution of the German Confederation was necessary. It adopted, and unfurled over its palace in the longstanding confederal capital, Frankfurt, a black-red-gold standard and invited German States to send delegates to discuss Constitutional reform. In the unsettled and challenging times invitations had already been sent out several days earlier by a self-appointed group of liberals based in Heidelberg that led to the convening, in Frankfurt on the 31st March, of a preparatory parliament ( Vorparlament ). At the close of five days in session, the Vorparlament recognised a fifty member committee as being responsible for the organisation of processes of election to a German National Assembly which was projected to convene in Frankfurt in May. It had also pronounced on Polish affairs thus :- "The German Union proclaims the partition of Poland to be a shameful injustice, and considers it the sacred duty of the German peoples to do their utmost to achieve her reconstitution". At the time of this meeting of the Vorparlement, although aspirations for various forms of political change were being widely voiced, all the traditional states of the German Confederation were still actually in being!!! There were a minority of more committed Republican delegates amongst those participating in the Vorparlament's deliberations who were disappointed not to secure the endorsement of radical-democratic constitutional aspirations or of the transformation of the Vorparlament itself into an on-going National Convention capable of assuming wide powers. After the Vorparlament concluded its brief days of holding sessions some of these more committed Republicans opted to raise the standard of actual armed revolution in the traditionally liberal state of Baden, and were supported in this by German exiles returning from France and by Polish radical elements-in-exile. In the event the received less support than they had hoped from the local populace and were overwhelmed by troops sent to suppress their radical-democratic rising. During these times the Federal Diet of the German Confederation was debating processes of election towards reaching decisions about the future of the Germanies but, in the event, it decided that it was not to be the authority behind such decisions and actually endorsed the elective programme of the Vorparlament thus consigning itself to a position of relative political obscurity. It was agreed by the German governments that extensive diplomatic, military and commercial powers were to be entrusted to an Executive Body that was to concern itself with the welfare of the Confederation without direct involvement in the framing of the Constitution. This Executive Body of responsible ministers was to be headed up by a titular Regent of the Empire. This title was awarded to Archduke John of Austria - a proposal that it should go to the King of Prussia having failed to find support. The Confederal Diet did however insist that it should continue to quietly exist pending the establishment of a new Constitution for Germany. In the meanwhile its functions were to be vested in the Regent of the Empire. The Vorparlament presumed that representatives should be sought from across the Germanic Confederation and also from non-Confederal territories dear to German sentiment such as East and West Prussia and Schleiswig. Whilst some presumptions relating to territorial representation were inevitable they could not but involve complications - the Austrian Empire was the most powerful of the states historically involved in the Germanic Confederation but also exercised sovereignty over immense territories that were outside the Confederation - the Danish king was the sovereign duke of Schleiswig and of Holstein. Ancient treaties deemed Holstein ( a confederal territory ) to be inseperable from Schleiswig. The Grand Duchy of Luxemburg was a longstanding member of the Confederation - it was also non-German speaking and its Grand Duke was simultaneously King of the Netherlands. The Czechs showed a preference that their homelands of Bohemia and Moravia, (where, despite being a major community, they had been living over recent centuries prior to 1848 in a condition of relative political disenfranchisment), should continue as provinces within the Austrian Empire rather than be brought in a close association with a German-national state.

In a letter of 11th April in response to an invitation by the Vorparlament to involve himself in proceedings as the representative for Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, the eminent historian Palacký, now showed himself to be something of a nationalistic Czech, declaring - "The letter of 6th April in which you, greatly esteemed gentlemen, did me the honour of inviting me to Frankfurt in order to take part in the business concerned 'mainly with the speediest summoning of a German Parliament' has just been duly delivered to me by the post. With joyful surprise I read in it the most valued testimony of the confidence which Germany's most distinguished men have not ceased to place in my views: for by summoning me to the assembly of 'friends of the German Fatherland', you yourselves acquit me of the charge which is as unjust as it has often been repeated, of ever having shown hostility towards the German people. With true gratitude I recognise in this the high humanity and love of justice of this excellent assembly, and I thus find myself all the more obliged to reply to it with open confidence, freely and without reservation. Gentlemen, I cannot accede to your call, either myself or by despatching another 'reliable patriot'. Allow me to expound the reasons for this to you as briefly as possible. The explicit purpose of your assembly is to put a German people's association [Volksbund] in the place of the existing federation of princes, to bring the German nation to real unity, to strengthen German national feeling, and thus to raise Germany's power both internal and external. However much I respect this endeavour and the feeling on which it is based, and particularly because I respect it, I cannot participate in it. I am not a German - at any rate I do not consider myself as such - and surely you have not wished to invite me as a mere yes-man without opinion or will...."

Palacký's letter was written against a social background where persons who could think of themselves as being Czech were encouraged by their peers to take an interest in, and to feel pride about, Czech history and literature. Such romanticisation of the Czech heritage was often expressed through German as Czech had yet to be firmly established as a literary language whilst most educated "Czechs" knew German. This revival had, in fact, been encouraged by Habsburg imperial administrators who hoped that such cultural enthusiams, as sponsored by the Habsburg system, would be potentially likely to win adherence to that system and also help to divert energies away from 'unsettling' political activities. Arrangements were made for the convening in Prague in June of a Congress of the Slavs living within the lands of the Habsburgs. Palacký emerged as a leading influence in this Slavic Congress and effectively championed an Austroslavism where the preservation of the Austrian Empire as a buffer against both German and Russian expansionism was seen as being essential to the best interests of the Slavs. Slavic national development within a federalized, and protective, Austrian empire being hoped for. In the event whilst elections to the Frankfurt Assembly went ahead in those parts of Bohemia mainly peopled by Germans participation was not forthcoming in predominantly Czech areas.

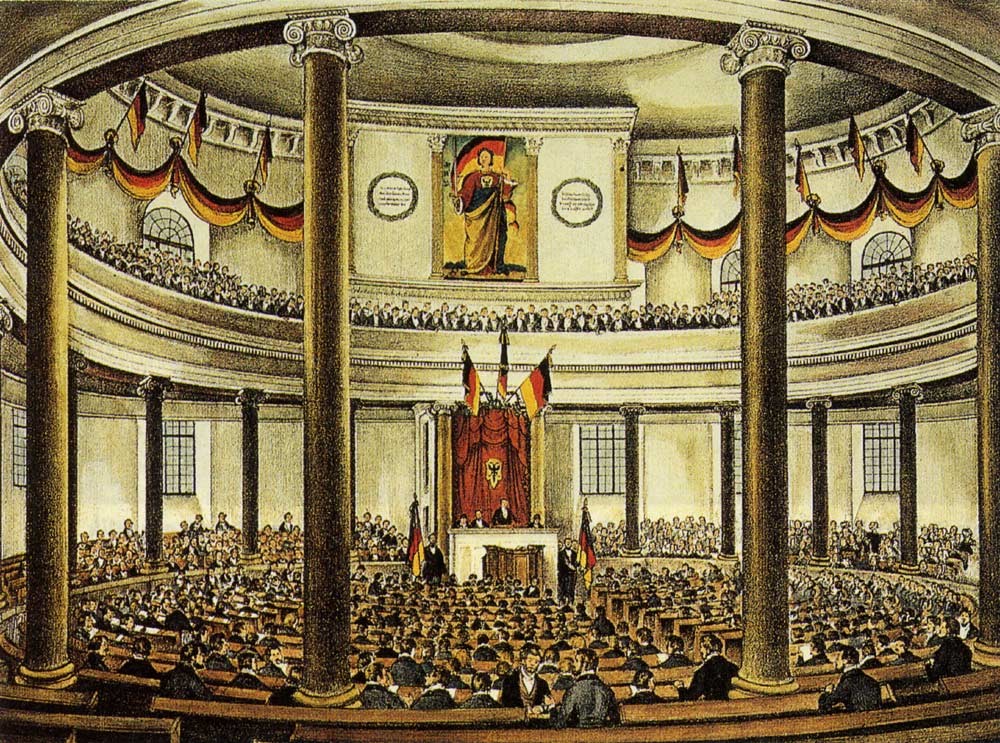

For this occasion the elegant elliptical interior of the Paulskirche was draped in German-national colours

with an imposing large-scale painting representing "Germania" being prominently displayed.

For this occasion the elegant elliptical interior of the Paulskirche was draped in German-national colours

with an imposing large-scale painting representing "Germania" being prominently displayed. This work, by

the artist Paul Veit, depicted Germania as a female figure standing against a background where beams of sunlight

shone through the tricolour fabric of the national flag. Germania was wearing a crown of oak leaves and had a pair

of shackles lying close to her feet that had evidently been recently discarded.

This work, by

the artist Paul Veit, depicted Germania as a female figure standing against a background where beams of sunlight

shone through the tricolour fabric of the national flag. Germania was wearing a crown of oak leaves and had a pair

of shackles lying close to her feet that had evidently been recently discarded.In this political and cultural atmosphere Heinrich von Gagern was elected as President, (or Speaker), of the National Assembly and in his opening speech suggested that :- "We wish to create a constitution for Germany, for the whole empire. The call and the authority for this creation lie in the sovereignty of the nation...Germany will be one...Unity she wishes, unity she will have."

The thirty-nine traditional states of the German Confederation continued to exist - with their own local forms of princely or state government as perhaps recently modified by the recent upsurge in political and constitutional aspiration. At the end of May the Frankfurt Parliament declared that the Constitution it was in the process of framing would be sovereign over all the governments of the former German Confederation. The Frankfurt Parliament further maintained that any legislation passed by princely or state governments would only be valid if consistent with the new constitution which would be based 'on the will and election of the German people, to found the unity and political liberty of Germany'.

In April 1848 Prussia, Brunswick, and Hanover, sent forces into Holstein after being asked to intervene by those assembled at Frankfurt at a time of a succession crisis, following on from the repudiation of the incoming Danish Kings personal Sovereignty as Duke, by the Estates of Holstein and Schleswig. In early May Prussian forces penetrated into the Danish province of Jutland. The Tsar of all the Russia's had let it be known that he disapproved of these actions by Prussia.

On 25 April 1848 the Habsburg Austrian Emperor had authorised a "Pillersdorf" constitution, drawn up by Minister of the Interior Franz von Pillersdorf, applicable to Austria which envisaged its continuance as a centralised state under a politically powerful ruler. This was at odds with opinion then being popularly expressed by liberal elements.

This constitution was partially intended by the Habsburg Austrian government of April, 1848, to place obstacles against the pan-Germanism it saw as potentially being embraced by many liberal Germans in Austria. The April 25 Constitution contained a vague phrase concerning the nationality issue:- "All the peoples of the Monarchy are guaranteed the inviolability of their nationality and language."One of the results of further disturbances in Vienna in mid-May, which prompted the Emperor to leave behind the turbulence of Vienna for the relative security of Innsbruck, was that the incoming political assembly (Reichstag) would have a role in the drafting of a new constitution. New electoral rules widened the franchise.

As the would-be German Authority the German National Assembly inherited a longstanding dispute with the Danish crown concerning sovereignty over the Duchies of Schleiswig and Holstein. Kings of Denmark had for some time been simultaneously sovereign Dukes of Schleiswig and of Holstein alongside their Danish sovereignty. Holstein was traditionally a member of the German Confederation, ancient treaties held Holstein to be inseparable from Schleswig in controlling sovereignty. Holstein was peopled mainly by ethnic Germans, as was southern Schleiswig. These ethnic Germans were excited by and attracted to the developments in Frankfurt. The Danish authorities meanwhile wished to incorporate the Duchies, and Schleswig in particular, under a common constitution with Denmark. Ethnic Germans in Holstein and Schleswig set up a provisional government in open defiance of the Danish authorities and in favour of adherence to the emergent German state. Prussian German forces intervened in what was now an active dispute. Prussian forces entered Holstein and Schleswig and many casualties ensued. Prussian armies continued their advance into the Danish province of Jutland. Many patriotic Germans volunteered for service against the Danish interest. The German National Assembly voted for the availability of substantial naval funding. Liberals in Western Europe had long deplored the condition of Poland being maintained principally under the repressive sovereignty of the Tsar but also, in the case of the Grand Duchy of Posen, under the rather more liberal sovereignty of the Prussian King. Those assembled at Frankfurt had, in the heady days of early April, declared support for the restitution of a Polish state as being "an Holy Duty of the German Nation." A political amnesty of March 20 following on from Frederick William's capitulation to populist feeling in Berlin included provisions which brought about the release of Polish revolutionists from imprisonment at Moabit. A triumphant procession composed of carriages pulled by enthusiastic Berliners conveyed the Polish revolutionist Mieroslawski and his followers from the prison to the palace. During the journey Mieroslawski proclaimed that Poles and Germans were brothers and waved a black, red, and gold banner in support of the changed situation in Prussia. In April there some unrest in which the Poles of Posen, who tended to be supportive of concessions favourable to the restoration of Polish nationality, were in opposition to Germans domiciled there. The Tsar of Russia was known to be completely opposed to any reorganisation of "his" Kingdom of Poland. By July many representives of the German minority in Posen, (a minority totalling some 700,000 persons), were seeking its incorporation into the German confederation. In the Frankfurt Parliament Wilhelm Jordan, (a Prussian delegate who had an established reputation as a liberal!), went so far as to tell the assembly that:- "It is high time that we awaken from the romantic self-renunciation which makes us admire all sorts of other nationalities whilst we ourselves languished in shameful bondage, trampled on by all the world; it is high time that we awaken to a healthy national egoism which, to put it frankly, places the welfare and honour of the fatherland above everything else..." In these times the Frankfurt Parliament voted by 342 votes to 31 ( with 75 abstentions ) to support a partition of the Grand Duchy of Posen. The motion voted on countenanced the full participation of those areas of Posen peopled by Germans in the workings of the Frankfurt Assembly. This inclusion of representatives was supported despite Posen being outside the historic frontiers of the Germanic Confederation. Representatives were also recognised from Schleiswig, another non-Confederal territory. On 26th April Frederick William IV authorised the incorporation of the German districts of the Grand Duchy of Posen, (some two-thirds of the land area of the Grand Duchy), into Prussia. The Frankfurt Parliament also resolved that those who had been returned from (mainly Germanic parts of) Bohemia should be regarded as fully representing Bohemia. Some European Powers began to be increasingly alarmed by such potential inclusions of widespread areas peopled by Germans in a future Germanic polity. The dispute with Denmark was brought to a close, partly due to the influence of international protest and mediation, in a Malmo Armistice of July 9 where Prussian and Danish soldiers were to be withdrawn and where Holstein and Schleswig were to be autonomous under the Danish Crown. This Armistice was agreed to by Prussia, under Russian and British persuasion and with Prussian commerce being seriously disrupted by Danish naval activity. Prussia did not enter into consultation with the German National Assembly. The provisions of the Malmo Armistice were unwelcome to German National sentiment and although the German National Assembly narrowly endorsed the Malmo Armistice after turbulent and agonised debate it had to call on Hessian, Austrian and Prussian forces to defend it against the street fighting of those of outraged national sentiment. Two prominent conservative delegates to the parliament and a number of protesting citizens lost their lives in these disturbances. The German Lands and central EuropeIt is practically necessary to consider the effects European Revolutions of 1848 in relation to Germany in association with the developments in central Europe as in 1848 what was then known as "The German Confederation" or as "The Germanies" was inextricably linked to central Europe due to the Habsburg Emperor of Austria, the most powerful ruler involved in the German Confederation, also also holding sovereignty over immense tracts of territory - and diverse peoples - in central and eastern Europe.The following maps may give an enhanced idea of the extensive territories and widespread peoples of Europe that may be held to have been "linked up" in the developments of 1848 due to initial shared dynatic sovereignties that had implictions when populist ideologies attempted to forge New Futures moreso under the principles of popular / national sovereignty.

"The nations of the Triune Kingdom, animated by the desire of continuing, as heretofore, under the Hungarian crown, with which the free crown of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia was voluntarily united by their ancestors; animated by the desire of remaining true to the reigning dynasty, ...animated by the desire of maintaining the integrity of the Austrian monarchy, and that of the kingdom of Hungary, ...making the following demands on the king's sense of justice:"

On April 8th a Serb deputation from the Banat in the south of the

Hungarian monarchy which was largely but very far from being exclusively peopled by Serbs, (local Serbs may have even been an overall

minority),

was admitted to the floor of the Diet of Pressburg, several

members of this deputation

were actually wearing Hungarian cockades, (see picture left), and the leader of this deputation, Alexander Kostic, declared

that his compatriots were ready to risk their blood against the Habsburgs in the interest of the independence of the

Hungarian kingdom. On April 8th a Serb deputation from the Banat in the south of the

Hungarian monarchy which was largely but very far from being exclusively peopled by Serbs, (local Serbs may have even been an overall

minority),

was admitted to the floor of the Diet of Pressburg, several

members of this deputation

were actually wearing Hungarian cockades, (see picture left), and the leader of this deputation, Alexander Kostic, declared

that his compatriots were ready to risk their blood against the Habsburgs in the interest of the independence of the

Hungarian kingdom.

In their subsequent private audience with Kossuth, the Serb deputation insisted that the Serb nation regarded the recognition of its language as essential. "What do you understand by ' nation ' ?" inquired Kossuth. "A race which possesses its own language, customs and culture," was the Serb reply, "and enough self-consciousness to preserve them." "A nation must also have its own government," objected Kossuth. "We do not go so far," Kostic explained ; "one nation can live under several different governments, and again several nations can form a single state." To this the minister replied that the government would not concern itself with the language of the home and would not even object to minor offices being held by non-Magyars, but that the Magyar interest demanded that no second race should be recognized as a nation and that only the Magyar language could bind the different nationalities together. Istvan Deak, in his work The Lawful Revolution, which considers these these unsettled times has Kossuth telling the Serb delegation that:- "The true meaning of freedom is that it recognizes the inhabitants of the fatherland only as a whole, and not as castes or privileged groups, and that it extends the blessings of collective liberty to all, without distinction of language or religion. The unity of the country makes it indispensible for the language of public affairs to be the Magyar language."Several of the deputation expressed the fear that open resistance might ensue if the southern Slavs should be disappointed in their hope that the new situation was to end all compulsion in the matter of language. "If the just claims of the Serb nation are not regarded by the Magyars," blurted out the young Stratimirovic, "we should be compelled to seek recognition elsewhere than at Pressburg." Kossuth's famous rejoinder, "In that case the sword will decide," put an end to the discussion and gave perhaps the first signal for the onset of an open racial and linguistic struggle where the nationalities opposed Magyarising centralism. On May 13, 1848, an autonomous Serbian Vojvodina, (a sort of Duchy and located in the south of the kingdom of Hungary), was self-proclaimed by local Serbian interests supported by the Serbian Orthodox church. The Serbian Congress which issued this proclamation declared undying loyalty to the Emperor but the government of that Emperor's Hungarian kingdom depicted this proclamation of autonomy as being treasonous. Magyar liberal nationalism seemed to offer a broad range of human and personal liberties, but nevertheless demonstrated an assimilationist state-nationalism that would deny many existential freedoms to any nation under the Hungarian Monarchy but the Hungarian. The fulfilment of Kossuth's aspirations would have involved national a marked degree of suppression for all the other races domiciled in the Hungarian kingdom; and it was directly due to his intolerance that the Magyars found themselves before the end of the summer ringed round by hostile nationalities in arms. The Hungarian kingdom's Slovaks and Rumanians came to emulate the national claims of the Croats and the Serbians and joined with them, with the tacit support of Vienna, against the centralising and Magyarising aspirations of the Hungarian interest led by Kossuth.

To say that in the spring of 1848 the Hungarians missed the chance to conciliate all their nationalities and therefore could not but lose everything, would be as wrong as to assert that there were no chances whatsoever. Newly triumphant Hungary could not be expected, voluntarily, to divide the realm into self-governing territories, with the whole inevitably coming under the control of the non-Magyar majority. Learning from HistoryAt Age-of-the-Sage we attempt to relate history in a manner demonstrative of the motivations of the diverse participants - holding that such an approach better allows for learning useful lessons from history about The Human Condition.The Magyars were not the first people to endeavour to create a 'progressive' state for themselves. Turbulent times can often give scope for the adoption of sweeping policies. If we look, in efforts to better understand The Human Condition, at revolutionary France in the years after 1789 we see that policies were adopted by the French Revolutionaries which also featured an official expectation of linguistic conformity. The France of 1789, with an overall population of some twenty-eight million persons, was the most populous state in western Europe by a wide margin. Territorially France was a result of a centuries long consolidation of provinces that had been brought under French royal sovereignty through dynastic marriages, dynastic inheritances, dynastic wars and other conflicts. Such processes had resulted in a high degree of regional linguistic diversity. The Revolutionary upheavals after 1789 occured in a French domestic situation where perhaps a million persons spoke Breton in their everyday lives, another million spoke German, an hundred thousand spoke Basque, there were another hundred thousand Catalan speakers, whilst Provence, in the south east, was the home of many historic dialects. Flemish and Italian were also spoken in certain border regions. In 1789 it is suggested that some forty per cent of the population of France as a whole could not communicate through the French language. Whilst only a sixth of the newly relevant administrative 'Departments' - (which the revolution had instituted in the place of the historic 'feudal' territiories of France), - all of which were located around Paris, were more or less exclusively French speaking. Ardent French Republicanism was largely an urban phenomenon. Its keenest supporters called each other "Citizen", demanded that "Careers be open to Talent" in a state supportive of "Liberty, Egality, and Fraternity." A Decree of 3 September 1791 anticipated the creation of a system public education for all citizens. Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand (1754-1838), one of the political great men of the time, proposed that there should be a primary school in each municipality such that "The language of the Constitution and the laws will be taught there to all; and this crowd of corrupted dialects, the last remains of feudality, will be forced to disappear; the new order of things demands it". The Kings of France had been prepared to exercise sovereignty over a "superficially" feudally structured realm featuring many historic duchies (Dukes) and counties (Counts) but had often ensured that their realm was actually locally adminstered by Royally appointed officials. The French kingdom as a whole had featured a fair degree of historic and localised linguistic diversity. The newly powerful would-be architects of a French Republic increasingly associated the concepts of "language" and "nation" and, as they conceptually struggled with issues of "unity" and "nationhood," it become evident that the "progressive" forms of "unity" and "nationhood" they had in mind were difficult to promote against this background of linguistic diversity and provincial regionalism. Some resistance being shown by non-French speaking provinces to the aspirations of the French Revoutionaries probably contributed to the generation of a mindset amongst the leading French Republican circles that saw such historically arising minority languages as being associated with the "feudalism" the French republicans were determined to displace. A Republican Decree under Robespierre, the Decree of Thermidor 2 (under a new 'French Republican' Calendar - July 20, 1794, old style), provided that henceforth all contracts had to be written in French. By its terms any civil servant, public officer, or any government official who, in the performance of their duties, drew up, wrote or subscribed official reports, judgements, contracts or other generally unspecified documents in idioms or languages other than French could be condemned to six months imprisonment. One of the moving spirits behind its adoption, the Abbe Gregoire, had presented a report entitled "Why and How the Patois Must be Destroyed and French Made Universal" to the National Convention on 16 Prairal Year II (4 June 1794). This report suggested that standard French was the mother tongue of only 15% of the population and maintained that 'the patois (Occitan, Provençal and all non-standard forms of French), together with Breton and Basque, represent the barbarism of centuries past and need to be obliterated and replaced by standard French'. Gregoires report called for the single and invariable use of "the language of freedom" in a "Republic one and indivisible". The Abbe, (a middle ranking cleric before the onset of Revolution), probably considered that he had liberal-progressive views. He had previously sought to promote the abolition of slavery and the abandonment of judicial powers to impose the death penalty. Similarly he had tried to save national treasures from destruction during revolutionary turmoils. Other aspirations to grant full citizenship to Frech jews were perhaps strongly tinged by hopes of their assimilation. The Abbe hoped that France would become a literate and progressive country graced with many schools and libraries and saw the pre-existing linguistic diversity as an obstacle to literacy and progress. As early as 8 Pluviôse Year II (January 27, 1794). Bertrand Barrère had stated in a major report on linguistic matters in relation to the revolution that : 'Federalism and superstition speak Breton, emigration and hatred of the Republic speak German, counter-revolution speaks Italian and fanaticism speaks Basque. Let us break these instruments of injury and error'. Barrère's report maintained that the state should make elementary education available to all children and went so far as to insist:- Citizens, the language of a free people must be one and the same for everyone.Within days of hearing the Barrère report the appointment of state funded teachers was authorised in diverse provinces where idioms other than French were in current use in daily life. Teachers will be required to teach everyday language and the French Declaration of Human Rights to all the young people of both sexes that fathers, mothers and guardians will be required to send to these public schools.

[Compulsory elementary education was introduced in France at the end of the nineteenth century. Jules Ferry, a lawyer holding the office of Minister of Public Instruction in the 1880s, is widely credited for creating the modern Republican school (l'école républicaine) by requiring all children under the age of 15, boys as well as girls, to attend. Under this newly universal system publicly funded instruction, through the medium of French, was to be free of charge and secular (laïque). Universal education, greater levels of literacy and of geographical and social mobility tended to compromise the vibrancy of the many dialects former spoken widely across the diverse and historic regions of France. [Whilst the French Revolution state, in some of in its earliest years, provides a clear case of assertive language-state identification, ("French Revolutionary" Liberty, Egality [fairness / equality of opportunity?] and Fraternity post 1789 not being applicable - it would seem - to language and languages), it must be acknowledged that it would entirely possible, (in Britain and Ireland, and in the Iberian Peninsula), to find people prepared to lament the ways in which the English language and the "Castilian-Spanish" language have tended to overwhelm other indigenous tongues - sometimes as a result of administrative policies pursued by the state in question.] In 1879 Edward Augustus Freeman, Professor of Modern History at Oxford University, wrote:-As the eighteenth century drew to a close literate sections of the populations of the diverse states of Europe began to aspire to constitutional governance. Literacy, educational, and cultural levels were all rising and locally previously "unconciously ethnic" groups were encouraged by a romanticisation of nationality that he recently come into being to become ethnically self-aware, to identify themselves with distinct linguistic and cultural heritages and to think of these as things which they ought to greatly value. In many cases the constitutional governance aspired to where the peoples were sovereign morphed into aspirations for constitutional governance associated with national sovereignty Where "unconciously ethnic" communities might continue to accept, (the constitutional governance of), ancient dynasties by whom their fore-fathers had been ruled, (and with whom "their own" princes may even have inter-married long, long, ago), and might continue to agree to participate in assemblies held through ancient languages such as Latin, (or largely held through the language of an ancient dynasty with some show of linguistic sensitivity to its loyal subjects), similar agreement to accept the novelty of the overall sovereignty of "another nation" - which, (given the emergence of ethnic-conciousness), expected the usage of its own language, in politics, in education, in administration and in employment - may not readily have seemed to offer justice or protection to potentially 'subject' nationalities - hence defiance, chaos, and harm. Given the historic multi-ethnic, or multi-communal, nature of the Habsburg realms in 1848 it is possible to see this deeply unfortunate situation as being - an horrendous accident waiting to happen - in that whilst the Austrian Empire, and its Hungarian monarchical aspect, had both had a validity in that their many constituent peoples could, in earlier times, give the historic state's existence their assent, receiving a degree of justice and protection and with local elites participating in politics and administration - it happened that the times, and with them human expectations, moved on such as to make former societal situations less tenable. This may have been particularly grievious in the case of the Hungarian Kingdom's aspect of the Habsburg realms as here participation of previously largely "unconciously ethnic" communities was readily possible through a shared knowledge of the Latin language that the sons of relatively priviledged families, regardless of communal or of confessional background, tended to learn as part and parcel of the then standard "classical" pattern of education.

"Rulers, Statesmen, Nations, are wont to be emphatically commended to the teaching which experience offers in history. But what experience and history teach is this - that people and governments never have learned anything from history, or acted on principles deduced from it. Each period is involved in such peculiar circumstances, exhibits a condition of things so strictly idiosyncratic, that its conduct must be regulated by considerations connected with itself, and itself alone."It can be suggested that European Societies were variously undergoing "tectonic" processess of change. Where it had been accepted in earlier generations of persons living within the historic Kingdom of Hungary that literacy, in Latin, was desirable, that social mobility was not to be expected and where sovereignity lay with dynastic rulers it had happened, in particular, amongst those same sections of the populace who were pushing reformist agendas in 1848 (i.e. educated middle class youth, young persons coming from the families of skilled artisans who aspired to having broader societal opportunities and the aristocratic intellligentsia of relatively "subject" nationalities) that literacy in the local "national" language was now increasingly seen as desirable, aspirations to social mobility were being expressed and sovereignty were seen as something that should be "that of the people" or at very least shared by peoples with their rulers. These developments had some parallels in Vienna where democratic processes resulting from the adoption of Universal Suffrage in the elections of 1848 had produced an overall majority of representatives drawn from various Slavic communal backgrounds. This Slavic majority passed resolutions in the Diet which abolished the previous acceptance of German as the language of proceedings through placing all languages on an equal footing in debates.

One Croat representative to the Diet, Ljudevit Gaj, was perhaps the leading figure in an Illyrian movement which sought to join together Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia and also several of the south-west provinces of Austria in a movement favourable to Slavic Revivalism. Like many romantic nationalists in these times, and later, across Europe and Scandinavia he was not native to the (in this case "Illyrian") nationality that was being championed. Gaj was the son of a German father and a Slovak mother and was born just north of Agram, in 1814, and developed an interest in Croatian history as he grew up. Whilst he was later being educated in German speaking universities he became influenced by a romanticisation of Pan-Slav cultural nationhood that held all Slavs to be brothers in the wider sense, but accepted the division of them into four main groups, one of which was the Southern Slav, or 'Illyrian', comprising the Croats, Slovenes, Serbs and Bulgars. The lands Gaj sought to identify with, "Illyria", or "Croatia with Dalmatia and Slovenia and possibly also Bulgaria and Serbia", had long been under the sway of external powers and foreign cultural influences to the extent that little remained of what was thought of as Croat identity. Gaj, through his involvement with his Croat language Illyrian News journal had gained a certain celebrity particularly in those parts where people could think of themselves as being "Croats" as a would-be champion of an awakening of a cultural patriotism that hoped to see a recovery of a "Croat-Illyrian" language, and a renaissance of "Croat-Illyrian" culture. In his efforts to recover "Croatian" as a South Slavic literary language, Gaj had personally devised a Latin character based script through which to better express "Illyrian" literature, aspirations and nationalist sentiments. The Magyar authorities, meanwhile, were alarmed by the upsurge of "Illyrianism" and had even tried to ban public utterance of the word "Illyria." Baron Jellachic, formerly a colonel of a Croatian regiment in the Habsburg service and more recently (March 1848) endorsed by the local interests as the principal magistrate, officially recognised as Governor of Croatia by the Habsburg Emperor (March 1848), was a close friend of Ljudevit Gaj! Soon after his appointment he expelled Magyar officials from Croatia in the aftermath of Magyar insistence in state-linguistic matters, in May forbade correspondence with the Hungarian government, and in June moved to restore the Croatian Diet at Agram. Under Hungarian diplomatic lobbying most of these measures by Jellachic were successively officially condemned by the Emperor even to the point of suspending Jellachic from office in early June. Local interests in Agram refused to accept Jellachic's dismissal and even invested him with many administrative and governmental powers. After an interview with an emissary from Vienna Jellachic recognised that a powerful faction in the Viennese court was sympathetic to the Croats defiance of the Magyars - all be it principally because this would contribute to a recovery of Habsburg power. Jellachic, although dismissed from office had continued to give fulsome assurances of loyalty to the Habsburg state system and had published an address to the numerous Croat soldiers based under Radetzky's overall command in Lombardy to continue in the Habsburg service and "not to be diverted from their duty to the Emperor in the field by any report of danger to their rights and to the nationality nearer home." Such statements had won him the support of many important persons in the higher reaches of the Austrian military and court. During these times the Habsburg authorities began to place more reliance on their Slavic peoples than on the Magyars as being reliable allies in the restoration of the Habsburg System. Against Hungarian wishes Jellachic was accepted as being able to continue to exercise authority in Croatia. The Habsburg authority let it be known that there was to be a recognition of "the equal rights of all nationalities" living within the Austrian state. Details of subsequent developments are to be found on our Widespread social chaos allows the re-assertion of Dynastic / Governmental Authority page.

Other Popular European History pages

The preparation of these pages was influenced to some degree by a particular "Philosophy

of History" as suggested by this quote from the famous Essay "History" by Ralph Waldo Emerson:-

|

|

Return to start of

The german revolution 1848

Frankfurt Vorparlament - German National Assembly