European History in 1848

The European map above, (as agreed at the Congress of Vienna of 1815),

saw some changes, (principally due to the emergence of Belgium and Greece),

before the onset of the European Revolutions of 1848-1849.

This present page is one of a series treating with themes unfolding during the history of the European Revolutions of 1848.

The content of these pages is not simplistically written but it is hoped that those who last the course will have a good insight as to how eminent historians have come to view these times as being a "turning-point at which modern history failed to turn".

In Europe in the middle of the nineteenth century it newly became possible, (due to such things as population increases and more widespread literacy), for a range

of Socio-Political-Economic "Populisms",

(including Liberalism, Constitutionalism and Nationalism), to have the inherent potency to testingly challenge the orderings of civil society, and the orderings of

dynastic statehood, that had been maintained by the Kings and Emperors who had been the holders of Sovereignty in Europe over previous centuries.

Whilst many (Liberal, Constitutional, Nationalistic or Socialistic) aspirational groups sought that changes would be conceded by their rulers it proved to be the

case that such aspirational groups often proposed changes that were unwelcome to other aspirational groups.

There were demands for some limited constitutional liberalisation and others for fuller democracy and popular sovereignty.

Some nationalistically aspirant groups seeking concessions to their aspirations for nation-statehood were often not willing to award concessions to potential minorities who would be living within the frontiers of said aspirant groups proposed national-sovereign territory.

There were instances of (often materially poor and socially radical) urban aspirant groups seeking socialistic concessions which (often materially poor and socially conservative) rural-dwellers found it difficult to sympathise.

There were demands for some limited constitutional liberalisation and others for fuller democracy and popular sovereignty.

Some nationalistically aspirant groups seeking concessions to their aspirations for nation-statehood were often not willing to award concessions to potential minorities who would be living within the frontiers of said aspirant groups proposed national-sovereign territory.

There were instances of (often materially poor and socially radical) urban aspirant groups seeking socialistic concessions which (often materially poor and socially conservative) rural-dwellers found it difficult to sympathise.

Radical socialist reformers sought justice for the "disinherited" classes, the peasants and the factory workers, while more moderate political reformers were concerned with protecting

and increasing the influence of the middle classes, the bourgeoisie and the professional groups. The radicals in general favoured a republican form of government while many

moderates were prepared to accept constitutional monarchy as a satisfactory substitute …

… Many of the revolutionaries, especially in the German Confederation and Italy, wanted to transform their homeland into a strong and united country, but their aims contradicted the nationalist aspirations of minority groups.

From the opening chapter to "Revolution and Reaction 1848-1852" by Geoffrey Brunn

… Many of the revolutionaries, especially in the German Confederation and Italy, wanted to transform their homeland into a strong and united country, but their aims contradicted the nationalist aspirations of minority groups.

From the opening chapter to "Revolution and Reaction 1848-1852" by Geoffrey Brunn

- * This Page * - The European Revolutions of 1848 begin

- A broad outline of the background to the onset of the turmoil and a consideration of some of the early events in

Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest and Prague.

- The French Revolution of 1848

- A particular focus on France - as the influential Austrian minister Prince Metternich, who sought to encourage the re-establishment of "Order" in the wake of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic turmoil of 1789-1815, said:-"When France sneezes Europe catches a cold".

- The "Italian" Revolution of 1848

- A "liberal" Papacy after 1846 helps allow the embers of an "Italian" national aspiration to rekindle across the Italian Peninsula.

- The Revolution of 1848 in the German Lands and central Europe

- "Germany" (prior to 1848 having been a confederation of thirty-nine individually sovereign Empires, Kingdoms, Electorates, Grand Duchies, Duchies, Principalities and Free Cities), had a movement for a single parliament in 1848 and many central European would-be "nations" attempted to promote a distinct existence for their "nationality".

- Widespread social chaos allows the re-assertion of Dynastic / Governmental Authority

- Some instances of social and political extremism allow previously pro-reform liberal elements to join conservative elements in supporting the return of traditional authority. Such nationalities living within the Habsburg Empire as the Czechs, Croats, Slovaks, Serbs and Romanians,

find it more credible to look to the Emperor,

rather than to the democratised assemblies recently established in Vienna and in Budapest as a result of populist agitation, for the future protection

of their nationality.

The Austrian Emperor and many Kings and Dukes regain political powers. Louis Napoleon, (who later became the Emperor Napoleon III), elected as President in France offering social stability at home but ultimately follows policies productive of dramatic change in the wider European structure of states and their sovereignty.

Some historical background to the Revolutions of 1848

Following on from the defeat of Napoleon which brought a French Revolutionary and Napoleonic period of turmoil which had lasted from 1789-1815 to a close, the conservatively inclined alliance of powers that had been ranged against him attempted to re-impose the sovereign powers of Monarchies and Empires.

These powers held Congresses to discuss the affairs of Europe and to orchestrate mutual efforts to maintain monarchical sovereignty.

After 1820 there were many instances of "constitutional-liberal" political upheaval on varying scales, in Spain and on the Italian Peninsula (resulting in counter-interventions by conservative / reactionary powers), in Russia, in Poland (national-constitutional-liberal and suppressed by Russian intervention), and in France.

Perhaps the most dramatically transforming of these upheavals being that in France where an illiberal "Legitimist" King of France was deposed and replaced by an "Orléanist" cousin who undertook to rule more liberally as "King of the French" in 1830.

European states as then traditionally organised, in addition to constitutionalism, liberalism and nationalism, also faced challenges from an increase in population creating more demands for foodstuffs, housing and employment. Such industrialisation as had begun to occur had sometimes impacted seriously on established craft industries bringing about significant displacement into unemployment. Many young persons from middle class backgrounds finished their years of education or training and emerged into an economic situation that was unwelcoming to their skills.

Levels of payment for both urban and rural workers tended to fall leaving many persons in a situation where they could hope to survive, health permitting and quite possibly in over-crowded and unsanitary conditions, but found it almost impossible to actually prosper.

Moreover, there was then no such thing as any system of social security in place to cater to the needs of those unlucky enough to fall on hard times through unemployment, illness or injury - or their dependants.

The European Revolutions of 1848 begin

The Springtime of Peoples

The revolutions of 1848-1849, (sometimes referred to in the German lands as the Völkerfrühling or the Springtime of Peoples), can perhaps be seen as a particularly active phase in the challenge populist claims to political power had intermittently been making against the authority traditionally exercised by the dynastic governments of Europe.

As with several instances of revolution in Europe previously that of 1848 was to have its major point of origin in France.

Poor grain harvests, the appearance of blight - an extremely serious disease - in potato crops, and generally depressed economic conditions across much of Europe in 1845-6 led to sharply rising food prices, unemployment, and a radicalisation of political attitudes.

Dramatic increases in the prices of food and fuel contributed to a situation where there were serious outbreaks of hunger-related Typhus fever, causing many fatalities. Trade was disrupted as there was less general spending as food came first where the poorest classes of people struggled to keep themselves fed and everyone found the necessities of life to be much more expensive. The levels of unemployment rose significantly. Such general economic dislocation brought with it increases in crime as persons broke the laws in their efforts to get food, fuel or cash. Those suffering from various forms of economic deprivation lost confidence in the authorities ability to help them and became somewhat resentful of occupational groups who could be seen as profiting from the crisis.

In many cases the authorities found it very difficult to receive customary tax revenues as the population had a significantly reduced ability to pay.

Hopes of social and political reform were somewhat encouraged by the election to the Papacy, as Pope Pius IX in June 1846, of an incumbent who soon thereafter followed policies perceived as being "Liberal" and by the fact of a "federal" Swiss interest, that was perceived by liberals as being progressive, prevailing in November 1847 over several Cantons leagued in a "Separate Union" or Sonderbund that had been supported in attempts to place limits on liberal reform by such reactionary powers as Metternich's Austria and Guizot's France.

During these times France was yet a monarchy under Louis Philippe but with his "Liberal" monarchy having few real supporters. Elections were held on the basis of quite limited suffrage - only some 170,000 wealthy men, (approximately one person in two hundred of an overall French population of 35 millions), could legally vote. Many French people felt excluded from any possibility of gaining wealth, many also felt that the bourgeois "Liberal" monarchy of Louis Philippe compared unfavourably with earlier "Glorious" eras of French Monarchy or Empire.

On 14th January 1848 the authorities banned a "banquet", one of a series of some seventy or so that had been held in Paris and in the provinces to protest, within the law, against such things as limitations on the right of assembly and the narrow scope of the political franchise, with the result that the it was postponed by its organisers.

At such politicised banquets participants could find the means to challenge the government by participating in toasts to such things as "electoral reform" or "parliamentary reform".

Although the banned banquet, now re-set for the 22nd February, was cancelled at the last minute there was some serious disturbance in the Paris streets during which extreme individuals opposed to the government intermittently attacked groups of soldiers. In such circumstances and in other situations soldiers fatally injured protesting citizens. Faced with such unrest Louis Philippe dismissed Guizot, his unpopular Prime Minister, on the 23rd and himself abdicated on the 24th. In the wake of these dramatic developments there was an establishment of a Provisional Government of a French Republic. On the 25th February a group of socialists, armed and carrying red flags, gathered in front of the Hotel de Ville (or City Hall) in Paris where their insistence secured a decree which proclaimed that the newly formed provisional government would undertake to provide work and would also recognise workers rights to combine.

"The Government of the French Republic binds itself to guarantee the livelihood of the workers by

providing work ... it will guarantee work for all citizens. It recognises that workers may organise in order to

enjoy the profits of their labour."

News of these events in Paris quickly reached other European cities as (what was then) a relatively new technology - The Telegraph System - allowed rapid dissemination of such momentous political news as this.

Across Europe those supportive of various forms of political liberalisation or political radicalism tended to see the Parisian developments as giving rise to an opportunity for the pressing of the case for liberalising or radical reform in their own cities and in their own states.

On the 27th of February in the Grand Duchy of Baden "German" black-red-gold emblems were widely evident and demands were expressed for such things as freedom of the press, constitutional governance and an all-German parliament. These demands were widely publicised in other German states. Such demands became known as the "March Demands", and were insistently required by the citizens of other German states of their own rulers.

Reforms were subsequently conceded, with varying degrees of reluctance, by the rulers of such historic and previously locally sovereign German states as Wurttemberg, Nassau, Hesse-Darmstadt, Bavaria and Saxony.

The Federal Diet of the German Confederation declared on 8 March that a revision of the Constitution of the German Confederation was necessary. It adopted, and unfurled over its palace in the longstanding confederal capital, Frankfurt, a black-red-gold standard and invited German States to send delegates to discuss Constitutional reform.

In the unsettled and challenging times invitations had already been sent out several days earlier by a self-appointed group of liberals based in Heidelberg that were intended to lead to the convening in Frankfurt on the 31st March, of a preparatory parliament where invited prominent persons could participate in deliberations on matters of immediate concern to all Germans prior to eventual elections to an all-German parliamentary body which was primarily intended to undertake the framing of future constitutional arrangements for the Germanic lands.

The Heidelberg liberals' invitations were thus sent out to individuals whom they respected and whom they hoped could make a positive contribution to such a liberal / parliamentary / constitutional programme. An "assembly of trusted men from all German peoples" was their aim for this pre-parliament and, given that the authority of the existing states of the Germanies was discredited, this Frankfurt Vorparlament, although somewhat irregularly called into being, gained acceptance in preference to the discussions of states' delegates as suggested by the Federal Diet of the German Confederation.

After an incident precipitated street fighting in Berlin, the capital of the Prussian Kingdom, King Frederick William withdrew his soldiers rather than see even more fatalities amongst his "beloved Berliners" and was subsequently seen by the populace to stand with his head bared in a demonstration of his regret, whilst the earthly remains of those Berliners killed in the street fighting were paraded with their wounds exposed.

That same day Frederick William rode in a stately progress through the streets of Berlin, prominently wearing a black-red-gold sash, accompanied by his generals who also wore black-red-gold emblems, along with his similarly-decorated ministers. The king presented himself as behaving as German leaders had in earlier times when they had " grasped the banner in situations of disorder and placed themselves at the head of the whole people. "

These "Germanic" colours were at one and the same time "revolutionary" and "conservative". They were open to being associated with contemporary German Liberalism and Nationalism having been adopted by "patriotic" Germany in the days of the Wars of Liberation against Napoleon but were also open to being thought of as being associated with the earlier "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation."

The following day a political amnesty brought about the release of the Polish revolutionist Mieroslawski and his forty followers from their two years of imprisonment at Moabit jail. A triumphant procession took them from the prison to the palace, in carriages pulled by enthusiastic Berliners. Mieroslawski waved a black-red-gold banner, proclaiming that Poles and Germans were brothers. Some Berliners, meanwhile, carried red and white "Polish" flags.

On the 22nd March the 190 Berliners who had fallen in the street fighting were given a state funeral with their funeral observances being attended by representatives of all branches of the government, wearing their golden chains of office.

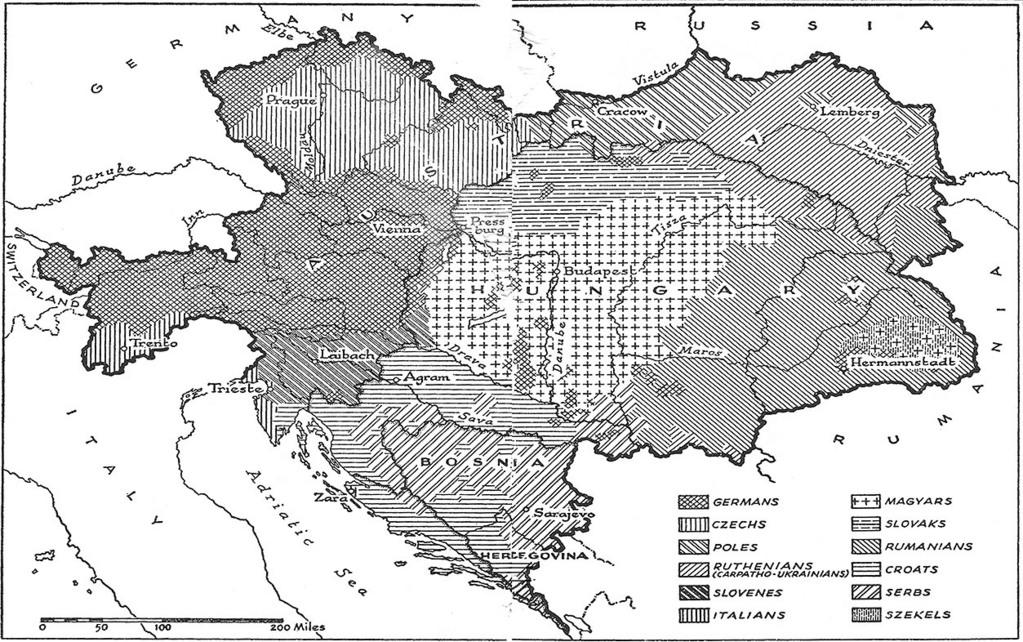

The above outline map shows how the immense territories of the Habsburg Empire lay both within and outside the frontiers of the German Confederation.

N.B. Lombardy and Venetia in the north of the Italian Peninsula, (south-west of the Tyrol and east of the Adriatic), were also under Habsburg sovereignty.

Peoples of the Habsburg / Austrian Empire:-

The rising tide of cultural and linguistic nationalism which Europe had experienced since the later eighteenth century was marked, in relation to the position of the Kingdom of Hungary within the Austrian empire, by demands being made for greater use of the Hungarian "Magyar" tongue.

The Emperor of Austria, in his capacity as King of Hungary, authorised the convening of a Hungarian political assembly, or Diet, at Pressburg (today's Bratislava) in 1823. The representatives thereto sought the recognition of the Magyar tongue as being appropriate for use in the administrative and judicial courts - this was assented to by the Habsburg authorities. It was also agreed that Magyar should displace Latin and German as the principal language in the administrative and political life in the Hungarian kingdom.

The Hungarian-Magyar kingdom had been established after the Magyars, as a powerful and somewhat martial people, had migrated into the Carpathian basin where they established their sway over some of the neighbouring Slavic peoples with the result that the kingdom in 1848 was dominated by the Magyars but was also peopled by various Slavic and other minorities.

By 1848 former losses of territory to the Ottoman empire had been recovered and Transylvania, together with certain areas of the Balkans, that had also been won from Ottoman control, were also seen as being open to becoming closely associated with the Kingdom of Hungary. The Latin tongue had been somewhat accessible to the other ethnicities represented at Pressburg as it was often represented in classical traditions of education besides being a prominent language of religion and scholarship. The Magyar tongue was more exclusive to the Magyars and has a reputation for being difficult to learn.

The Magyars, in fact, although they formed the most numerous individual ethnic group in the Hungarian Kingdom, and the traditionally most powerful one, only comprised perhaps four-in-ten of the population of the kingdom which was also peopled by Romanians, Slovaks, Serbs and others. In the event Magyar interests tended to insist on the full utilisation of their tongue even in areas where the were not themselves in the majority.

The nationalist, Kossuth, was prominent at a Diet of the Hungarian Kingdom held at Pressburg in 1844 in securing the position of the Magyar tongue as the official language, and as the language of public education. After 1847 the proceedings of the Hungarian Diet were conducted through Magyar instead of Latin.

The several ethnic groups domiciled under the auspices of the Hungarian Diet were also variously influenced by romanticisations of their own local traditions of nationality, the Croats, in particular, had experienced a pronounced development of a romanticised national consciousness, and were much inclined to resist potential Magyarisation focussing their aspiration on the recovery of an "Illyrian" language.

Early in 1848, after hearing of the developments in France Kossuth made a speech in support of a constitutionally defined governmental system for Hungary at a session of the Pressburg Diet of 3rd March which concluded with words imparting hostility to then position of the Kingdom of Hungary together with hopes for a happier future:-

... "From the charnel-house of the Viennese system a poison-laden atmosphere steals over us, which paralyses our nerves and bows us when we would soar.

The future of Hungary can never be secure while in the other provinces there exists a system of government in direct antagonism to every constitutional principle.

Our task it is to found a happier future on the brotherhood of all the Austrian races, and to substitute for the union enforced by bayonets and police the enduring bond of a

free constitution".

Kossuth seemed to expect that the principal linkage with Austria would be that of a

personal union through the monarchy of Kings of Hungary who were simultaneously Emperors of Austria.

Magyar aspirations became somewhat distilled into twelve specific demands:-

I. Liberty of the press, and removal of all censorship.

II. A responsible ministry.

III. An annual diet at Pesth.

IV. Equality of all classes in the eye of the law.

V. A national guard.

VI. An equal distribution of taxes.

VII. The abolition of all territorial laws.

VIII Trial by jury.

IX. A national bank.

X. That the army should swear fidelity to the constitution, and that the government should enlist native soldiers, and dismiss all foreigners.

XI. A general amnesty for political offences.

XII. Union of Transylvania with Hungary.

II. A responsible ministry.

III. An annual diet at Pesth.

IV. Equality of all classes in the eye of the law.

V. A national guard.

VI. An equal distribution of taxes.

VII. The abolition of all territorial laws.

VIII Trial by jury.

IX. A national bank.

X. That the army should swear fidelity to the constitution, and that the government should enlist native soldiers, and dismiss all foreigners.

XI. A general amnesty for political offences.

XII. Union of Transylvania with Hungary.

There was also unrest in Vienna which culminated, on 13th March, already designated as the date for the discussion of reform petitions in the Lower Austrian diet (the legislative chamber where the non-Hungarian lands of the empire held political debates), in public turmoil where several thousand university students paraded through the streets of Vienna in support of far-reaching liberalising reforms.

These students were joined by many similarly dis-satisfied citizens.

After the leaders of the students had proceeded into a government building to present their petition some of the numerous students gathered outside believed that those leaders had placed themselves in a situation where they could be captured by the authorities. After shouting out of windows to their many friends outside the students' leaders were rescued, with some damage to property, from the building.

Archduke Albrecht, a member of the imperial family, who held an high military rank, subsequently approached a crowd of protesting citizens, on foot, urging those gathered together to disperse, but was hit on the head by a missile.

A situation continued for some time where figures of authority exhorted protesters to disperse and missiles were thrown by some protestors. Eventually, a company of soldiers whose commanding officer had been knocked unconscious by one of these missiles actually fired their weapons into the crowd - a number of injuries and a few fatalities occurred.

These events led to the Emperor ordering a withdrawal of soldiers to their barracks within the city.

Many Viennese citizens were deeply alienated by the use of military force against the civilian population. Shops were looted, factories were wrecked - yet soldiers, who might in other circumstances have been looked to as potential restorers of order, were now widely unwelcome on the streets.

The Viennese Citizen Guard, traditionally a somewhat ceremonial body composed of better-off burghers (citizens), offered to assume responsibilty for the maintenance of order, and demanded that an "Academic Legion" composed principally of students and academics was officially recognised and allowed to carry arms.

Prince Metternich the Austrian statesmen who had done so much since the humbling of Napoleon (1815) to organise the Princes of Europe in opposition to the spirit of Revolution that had been stirring since 1789, and who had for years been serving the Habsburg Court as "Head of Chancellery and Minister of Foreign Affairs", lost the confidence of the Imperial Family and had little choice but to go quietly into exile.

Metternich was a figure of European significance as a mainstay of reactionary governance: his fall from power greatly encouraged liberal, constitutional and national aspirations to be expressed by diverse sections of the populations of the states of Europe.

The Austrian authorities made the further concession of abolishing the formerly quite pervasive censorship of the press.

In circumstances where the Citizen Guard had been reconstituted as a National Guard, within which the students' Academic Legion was also incorporated, and where the National Guard was taking the side of the protesting citizenry censorship would have probably been impossible to maintain.

Further insight into the political and social atmosphere then in place in Vienna can be perhaps gauged from the fact that a general amnesty for political offences was declared some days later.

On the evening of the 15th March a mounted herald read a proclamation outside one of the gates of the palace which declared that the Emperor "had taken the necessary steps to convoke, as quickly as possible, representatives of all provincial Estates ... with increased representation for the burghers, for the purpose of the Constitution which We have decided to grant."

There had already been much tension between landlords and those persons who actually cultivated the land in these times where, for several years in succession, notably wet weather had hampered crop growth and harvesting in many areas of the Austrian Empire. Potato blight, (at that time a crop disease new to Europe), had catastrophically diminished the prospective supply of the mainstay foodstuff of such populous regions as Silesia, and there was a serious outbreak of cattle disease in Hungary.

Even in good times those persons who actually cultivated the land often won only a meagre living for themselves after paying monies to the landlord as rent, to the church as tithes, and to the authorities as taxes. They were also expected to perform so-called "Robot" obligations where those who cultivated land as tenants were also expected to work one or more days per week on lands owned by individual landlords and where the crops or herds were being farmed for the individual landlord's economic benefit.

Such had been the traditional ordering of rural life for several centuries.

In March 1848 the Austrian Emperor, (or rather his advisors as then holder of that title, although widely respected, was a somewhat simple-minded and good-natured individual), authorised the announcement of the principle of the abolition of the Robot obligation "within a year, at the latest by 31 March 1849".

There was to be some compensation paid to the landlords with the amounts being settled upon by local Diets or political assemblies.

Those persons who farmed as tenants had, in fact, often recently stopped performing the Robot obligations they were nevertheless deeply grateful to the Emperor for giving legal backing to the abolition of a burden they regarded as particularly onerous.

Given that more than ninety per cent of the population of the Empire in those times were rural dwellers gratitude associated with the abolition of the Robot obligation tended to provide a basis for an acceptance of the continued authority of the Emperor in the countryside.

It was in any case a problematic reality that it was urban, relatively prosperous and educated, persons who were likely to feel frustrated by lack of opportunities in the Habsburg Empire's economic life and state bureaucracy.

Urban, relatively prosperous and educated middle class persons, intellectually engaged artisans and some liberal aristocrats were also more likely to have been influenced by romanticisations of nationality, which had become fashionable across Europe after circa 1770, where it was held that individuals should prize and cultivate the language and culture of the ethnic or national group within which they felt, (or could feel), they belonged. The Habsburg authorities had actually tended to facilitate such linguistic and cultural enthusiasms seeing them as possible diversions of the energies of their participants away from potentially more problematic political activities. In association with such romanticisation of nationality, and the wider implications of such societally impacting national consciousness, a situation began to arise where less powerful emergent ethnic or national groups increasingly began to complain when locally powerful emergent ethnic or national groups, such as Germans, Magyars, Poles and Italians, attempted to impose their languages and cultures on them.

During these times the Habsburg administration was faced with a wide array of demands for liberalising and nationalist concessions being made on behalf of its constituent peoples.

The Poles of Galicia drew up an address, which was presented on March 19 to the governor of Galicia, Count Franz Stadion, demanding of the Austrian Emperor such things as:-

The nomination of a committee of Galician Poles, entrusted with a reorganization of the laws and institutions of their province on a purely national basis.

That awardance of a separate constitution to the Poles of Galicia, with powers being conceded to elect representatives on the basis of universal suffrage to serve in a national diet.

The recognition of legality in relation to public meetings being held to discuss all political questions.

The organisation of a separate national guard and the formation of an army of native Poles.

The introduction of the Polish language into all schools and also into public offices; where it was anticipated that some dismissals or redeployments of German speaking office holders in favour of Polish speaking substitutes might prove to be necessary.

Galicia, however, was peopled by Ruthenians, (or Ukrainians), in the east, as well as Poles in the west. It would seem that Stadion,

with the intention of lessening the impetus of Galician-Polish national aspiration, gave some encouragement

to the relatively historically dispriviledged Ruthenians in making submissions, on April 19, to the Habsburg Emperor intended to

establish protections for their nationality against suppression.

That awardance of a separate constitution to the Poles of Galicia, with powers being conceded to elect representatives on the basis of universal suffrage to serve in a national diet.

The recognition of legality in relation to public meetings being held to discuss all political questions.

The organisation of a separate national guard and the formation of an army of native Poles.

The introduction of the Polish language into all schools and also into public offices; where it was anticipated that some dismissals or redeployments of German speaking office holders in favour of Polish speaking substitutes might prove to be necessary.

After mid-March when news of the recent serious civil unrest in Vienna, (including the fall from power of Metternich - much disliked by liberals in the Italian peninsula), reached Milan there was civil turmoil where an estimated ten thousand persons actively sought the freedom of the press, the replacement of the existing police force by a newly formed civil guard and the convening of a national assembly.

The Austrian authorities in Lombardy were initially somewhat unprepared to meet these protests head-on and, after a captured Austrian administrator made concessions to the protestors, (including the signing of proclamations of the establishment of a Provisional Government and of a National Guard), the Austrian military commander Radetzky, (a general of wide experience who was actually then more than eighty years of age), continued to attempt to regain control with the result that an intense combat ensued over some two or three days.

In the event Radetzky's forces estimated at some 13,000 men, suffered from a significant number of desertions whilst there was a real threat that the Piedmontese-Sardinian Kingdom, with its tens of thousands strong armed forces, could intervene against the Austrian interest. Given these considerations the Austrian forces in Lombardy were withdrawn from Milan. Radetzky subsequently decided to base his forces, in a defensive posture, upon a formidable group of fortresses known as the Quadrilateral located towards the strategic Brenner pass, through which Austrian forces traditionally crossed between Austrian territory and the Italian lands through the Alps.

Germanic national-liberal enthusiasm resulted in the black-red-gold "German" colours being worn in the button holes of many students in the important "Austrian" cities of Graz and Vienna - and were often worn by members of the Academic Legion then active in Viennese events. In early April the traditional Black and Yellow colours of the Austrian Habsburgs were replaced on the cathedral and the university in Vienna by the hands of Germanic national-liberal enthusiasts, by the black-red-gold "German" colours.

Black-red-gold emblems were even also raised over the Austrian Habsburg's imperial palace whilst crowds outside sung Germanic national-liberal songs.

Young, and not so young, middle class Austrian Germans tended to see some potential for enhanced liberty and progress through associating themselves, and their country's future, with the proceedings of the Frankfurt Parliament.

This widely evident adoption of Germanic national-liberal enthusiasm by powerful sections of opinion in Vienna drew the Austrian lands towards a full participation in a process unilaterally authorised on 2 April by the Frankfurt Vorparlament whereby a Committee of Fifty, appointed by the Vorparlament itself, would be entrusted with the framing of a future German constitution "solely and entirely, without any consent from the governments."

The Vorparlament did expect that a few delegates to the Committee of Fifty would come from the broader lands of the Austrian Empire yet Frantisek Palacký, one of the persons it invited to participate in this process, declined to attend, (as the representative for Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia), in a famous and historically significant letter:-

The letter of 6th April in which you,

greatly esteemed gentlemen, did me the honour of inviting me to Frankfurt

in order to take part in the business concerned 'mainly with the speediest

summoning of a German Parliament' has just been duly delivered to me by

the post.

With joyful surprise I read in it the most valued testimony of the confidence which Germany's most distinguished men have not ceased to place in my views: for by summoning me to the assembly of 'friends of the German Fatherland', you yourselves acquit me of the charge which is as unjust as it has often been repeated, of ever having shown hostility towards the German people. With true gratitude I recognise in this the high humanity and love of justice of this excellent assembly, and I thus find myself all the more obliged to reply to it with open confidence, freely and without reservation.

Gentlemen, I cannot accede to your call, either myself or by despatching another 'reliable patriot'. Allow me to expound the reasons for this to you as briefly as possible.

The explicit purpose of your assembly is to put a German people's association [Volksbund] in the place of the existing federation of princes, to bring the German nation to real unity, to strengthen German national feeling, and thus to raise Germany's power both internal and external. However much I respect this endeavour and the feeling on which it is based, and particularly because I respect it, I cannot participate in it. I am not a German - at any rate I do not consider myself as such - and surely you have not wished to invite me as a mere yes-man without opinion or will....

With joyful surprise I read in it the most valued testimony of the confidence which Germany's most distinguished men have not ceased to place in my views: for by summoning me to the assembly of 'friends of the German Fatherland', you yourselves acquit me of the charge which is as unjust as it has often been repeated, of ever having shown hostility towards the German people. With true gratitude I recognise in this the high humanity and love of justice of this excellent assembly, and I thus find myself all the more obliged to reply to it with open confidence, freely and without reservation.

Gentlemen, I cannot accede to your call, either myself or by despatching another 'reliable patriot'. Allow me to expound the reasons for this to you as briefly as possible.

The explicit purpose of your assembly is to put a German people's association [Volksbund] in the place of the existing federation of princes, to bring the German nation to real unity, to strengthen German national feeling, and thus to raise Germany's power both internal and external. However much I respect this endeavour and the feeling on which it is based, and particularly because I respect it, I cannot participate in it. I am not a German - at any rate I do not consider myself as such - and surely you have not wished to invite me as a mere yes-man without opinion or will....

Palacký thought of himself as being of Czech ethnicity and became prominent over ensuing weeks and months in promoting Austro-Slavism where the several Slavonic ethnicities present in the Austrian Empire strongly supported its continued existence as being the best protector of their several Slavonic ethnicities.

In the event several "German Austrian" delegates from the Austrian Empire did attend the proceedings at Frankfurt but seem to have seen themselves as acting to rein in any revolutionary tendencies appearing at Frankfurt and to maintaining a high degree of continued distinct sovereignty for Austria.

On 25 April the Austrian authorities issued an Imperial Patent, commonly known as the Pillersdorf Constitution, which offered to provide constitutional arrangements for the future governance of most of the non-Hungarian and non-Italian lands of the Austrian Empire. Radically inclined opinion in Vienna tended to object to the imposition of a Constitution by the authorities - particularly one that recognised the Emperor as having a right of veto over future policies a government might wish to pursue.

The minister who had succeeded Prince Metternich resigned. Several liberal amendments, (including those of there being two parliamentary houses rather than just one, and of a broadened franchise), to the proposed Imperial Patent were offered by the Austrian authorities.

In the event mass meetings were held on 15 May where the National Guard and workers demanded the concession that an Assembly, with full responsibility for the framing of a Constitution, could be elected by a broad and popular franchise.

On 16 May the Emperor and his ministers accepted the convening of such a popular Constituent Assembly. It was also accepted that the National Guard would share in sentry duties at the Imperial Palace.

Within days, however, the Imperial family took flight from the turbulence of Vienna. The Emperor and his wife had apparently left the palace in a carriage to make a personal visit nearby but left the city to be driven through the night and well into the following day to reach the relative calm of Innsbruck where they were joined, some hours later, by the Emperor's brother (and presumptive heir), his wife, and their younger children.

The Imperial family forwarded a proclamation to Vienna which stated that the Emperor had been forced to depart from Vienna as:-

"an anarchical faction, supported chiefly by the Academic Legion, which had been led astray by foreigners, and

by certain detachments of the Citizens' and National Guards, had, wavering in their accustomed loyalty, wished to deprive him

of his freedom of action".

Back in Vienna conservative elements tried to assert their version of "order" in support of the departed Emperor but were gradually

obliged to recognise the authority of a comparatively radical "Committee of the Burghers, National Guard, and Students of Vienna for

the maintenance of peace, security and order and the preservation of the people's rights" known for short as the "Committee of Safety".

Within days, whilst it probably not in line the wishes of the more sober members of this Committee, an order of monks considered to be ministering, in particular, to wealthier persons was subjected to diverse harassments and felt a necessity to flee the city. Across the Habsburg lands very many persons could condemn this as being anti-religious.

Witch hunts were pursued by unruly elements against prominent conservatives, aristocrats and wealthier persons, many of the more privileged citizens left Vienna taking their purchasing power with them.

Economic woes began to pile up for the Committee of Safety. Both the rich and those of more modest means became more cautious about their spending in the uncertain times. Domestic tradesmen and factories became unsure of reaching a ready market for their services and their produce due to the knock-on effects on consumption associated with widespread and deep concern about the potential disturbance to normal life resulting from social and political instability. Foreign suppliers of raw materials became nervous about actually being paid. Levels of unemployment rose markedly. The Austrian currency plummeted in value on international exchanges. Taxation became even more difficult to raise. Claims on the public purse tended to increase.

Although there was no established system of Social Security the "Committee of Safety" were persuaded to assume responsibility for funding the financial maintenance of persons unable to find employment. The differing rates of payment decided upon for men, for women, and for juveniles, actually compared well with the higher rates then being paid by private enterprises for unskilled employees. The "Committee of Safety" proved unwilling or unable to prevent such unwelcome developments as an influx of unemployed persons from the provinces or the drawing of such maintenance several times on the same day by opportunists who could present themselves at a number of payment offices.

Conservatives, and even Liberals who had been in favour of some reform, could now be disenchanted by such things as the flight of the imperial family, by the departure of the wealthy classes (and their spending power), and, (whilst they might concede that unemployed people needed some level of support), the reality of some 50,000 persons claiming maintenance from the state at considerable and seemingly open-ended expense to the public purse brought with it real concerns for the future.

Whilst Conservatives and Liberals might concede that the crisis had some natural causes, (appallingly bad weather causing bad harvests, with crop and animal disease outbreaks adding significantly to the situation), they could also blame radical excesses for worsening the the picture.

As March continued, and into April, there was a rush of laws passed by the Hungarian Diet in support of the administration there being free of Austrian control. Hungary, and Transylvania styled as "the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen" were deemed a single state.

This proposed political union between Hungary and Transylvania was, however, subject to ratification by the Transylvanian Diet.

Croatian representation in the Hungarian Diet was increased from three to eighteen delegates in recognition of an expected Croat participation in the proceedings of the Hungarian Diet.

It was understood that the Diet of the Hungarian Kingdom would in near future relocate away from Pressburg to hold its sessions at Pest (an important town lying alongside the river Danube and just across that river from Buda - hence today's Budapest). The ministry there would be fully responsible for many areas of governance.

The Austrian Emperor, appearing in person at a final meeting of the Hungarian Diet in Pressburg, formally accepted these changes on 11th April.

In early April the Austrian Emperor promised in a Charter of Bohemia that there should be a responsible separate political estates (assemblies) for Bohemia and for Moravia and that there would be substantial concessions to the Czech language. Czech aspiration further sought that Bohemia and Moravia with Silesia should be regarded as a single administrative unit - "the Lands of the Crown of St. Wenceslaus" - but this was not fully conceded.

Czech, Polish and other Slav elements within the lands of the Habsburgs reacted to the events of 1848 and to the nationalistic and constitutional developments in the Germanic lands by arranging for a pan-Slav Congress to convene at Prague in early June.

After news of the dramatic developments in Vienna in mid-March reached Agram (Zagreb), the Croatian capital, a long simmering Croatian-Illyrian nationalism stirred into political life seeking a Croatian state with complete political independence from Hungary. Although Hungarian representations to the Emperor produced an attempt, dated 7 May, to contain the Croat-Illyrian nationalism led by a general named Josip Jellachic, this was followed by an explicit refusal by Jellachic to submit to the authority of an Hungarian Diet and the unconstitutional calling, on his own authority, for the meeting of a General Assembly of Croatia to take place in early June at which deputies from all the other Austro-Slavic countries were deemed to be entitled to attend.

Hearing of this some Serbs proposed that Serb representatives should present themselves at this General Assembly in order to take part in its proceedings. Serbs and Croats share a language, Serbo-Croat, and, in 1848, felt some ethnic kinship with each other.

Although the Habsburg authorities attempted to discourage this Serb participation in the proceedings of this General Assembly Serbian interests openly defied the Habsburg authorities and arranged for Serb delegates to attend.

On 29 May, Baron Wesselényi, who had actually personally done much to oppose the Union of Transylvania with Hungary during earlier proceedings of the Transylvanian Diet, appeared in the Upper House of the Hungarian Diet, the House of Magnates, where he was also entitled to take a seat, and attempted to make a case that some concessions to the nationality of the numerous Romanians within Transylvania was necessary to provide a basis for future co-operation and asking that the Hungarian Diet "pass a law that the nationality of the Romanians shall be respected."

Prior to the revolutionary events of 1848 the political representatives of three traditionally recognized "nations", (Magyars, Székelys - a Magyar-speaking subgroup very closely linked with the Magyars, and the Saxons), had been politically dominant in Transylvania, with the Magyar element being pre-eminent!

A measure passed by the Diet in 1847 had given a favoured position to the Magyar language in the future administration of Transylvania.

The Saxons were a community of historic Germanic origin but then present in Transylvania for some six hundred years after having been invited in by earlier Magyar rulers to assist in the defence of their realms. The descendants of these incomers were allowed extensive territorial autonomies and established themselves as craftmen, merchants and as members of the professions living in largely self-governing, Germanised, towns and villages over the course of time.

The numerous Romanians living in Transylvania, however, did not receive politically relevant recognition as a "nation."

The rules in relation to persons qualifying as electors in the various administrative areas of the Habsburg territories had changed markedly as an outcome of the revolutionary turmoil in Vienna and Budapest, and it was obvious that any fresh elections to the Transylvanian Diet conducted under those new rules would also inevitably produce a very substantial Romanian representation.

Thus it was against a background of a probable imminent political transformation within Transylvania that on May 30, 1848, the Transylvanian Diet went ahead and voted in favour of the Union of Transylvania with Hungary.

Although Romanians comprised the majority ethnic community in Transylvania, and were then unmistakably giving voice to aspirations towards changes that would eliminate the longstanding political, economic and cultural disenfranchisements under which they felt themselves to have been living, Kossuth subsequently dismissed Baron Wesselényi's proposed concessions declaring that he knew nothing of a Rumanic, or a Croatian people, and recognised only Hungarian citizens.

Within days of the vote of May 30 some sporadic clashes, between the authorities who sought to implement the Union, and Romanians, who were very reluctant to accept it on political and linguistic grounds, were being reported.

Many of the Saxons became increasingly concerned for their political and linguistic future if Transylvania was incorporated into an expanded Kingdom of Hungary and tended to make common cause with the Romanians.

Over ensuing weeks inter-communal clashes in Transylvania grew in scale and intensity as a tangled situation had arisen where some seventy-five per cent of the Transylvanian population declined to give consent to the Union whilst the remaining, historically politically dominant, twenty five per cent favoured it and were supported in this by those who held the levers of power in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Jonathan Sperber, in Chapter 5 of his The European Revolutions, 1848-1851, gives this summary of the European situation:-

By late spring 1848, the Habsburg Empire looked like a hopeless case: the monarchy's northern Italian possessions in revolt, invaded by a Piedmontese army

and largely cleared of Austrian troops; three different "national" governments in Vienna, Budapest and Zagreb each claiming sovereign authority; Polish,

Romanian, Slovenian, Serb, Czech, and Slovak national movements aspiring to a similar sovereign status; a mentally incompetent monarch and his court in flight

from the capital to the provinces; a state treasury completely bare.

In April Frantisek Palacký had declined to become involved in the proceedings at Frankfurt declaring in his letter:-

"I am not a German - at any rate I do not consider myself as such", and, in the same letter, making such statements as:-

... You know that the south-east of Europe

along the frontiers of the Russian Empire is inhabited by several peoples

significantly different in origin, language, history and culture - Slavs,

Wallachians, Magyars, and Germans, not to mention the Greeks, Turks and

Schkipetars - of whom none is strong enough by itself to put up a

successful resistance in the future against the overpowering neighbour in

the East (i.e. The Russian Empire); they can do that only when a single and firm bond unites them

all with one another. The true life blood of this necessary union of

peoples is the Danube: its central power, therefore, must not be too far

distant from this stream if it wants to be and to remain at all effective.

Truly, if the Austrian Empire had not already existed for a long time,

then one would have to hurry in the interest of Europe and the interest of

humanity to create it.

... When I cast my glance beyond the frontiers of Bohemia I am impelled by natural as well as historical causes to direct them not towards Frankfurt but towards Vienna, and there to seek the centre which is natural and is called to secure and to protect for my people peace, freedom and justice.

... For the salvation of Europe, Vienna must not sink down to the level of a provincial city!

... I shall always be glad to co-operate in all measures which do not endanger Austria's independence, integrity and the development of her power.

Palacký had made considerable efforts during the following weeks in

promoting Austro-Slavism which had resulted in the arranging of a Pan-Slav congress to be held in Prague early in June, 1848

bringing together in one place representations from across the "Austrian" Slavic lands - Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenes, Croats, Serbs and Slovenes.

... When I cast my glance beyond the frontiers of Bohemia I am impelled by natural as well as historical causes to direct them not towards Frankfurt but towards Vienna, and there to seek the centre which is natural and is called to secure and to protect for my people peace, freedom and justice.

... For the salvation of Europe, Vienna must not sink down to the level of a provincial city!

... I shall always be glad to co-operate in all measures which do not endanger Austria's independence, integrity and the development of her power.

Prior to the opening session the conveners of the congress (who were mostly Czech) issued a proclamation announcing that:-

"We solemnly declare that we are resolved to remain loyal to the House of Hapsburg-Lorraine, which reigns over us by virtue of

hereditary right and constitutional principles.

We are resolved to maintain the integrity and independence of the empire by every means in our power. We repel all the accusations of separatism, "pan-Slavism", and pro-Russian tendencies which may be brought against us by evil-disposed calumniators.

... Our national independence and our union depend on the maintenance of the independence and integrity of the Austrian empire. The task which we essay is essentially conservative, and there is nothing to cause inquietude to our fair-minded and liberal fellow-citizens of other nationalities".

From this it might well be thought that the Habsburg system might find firm support amongst its numerous Slavic peoples, (which,

if numbered together, actually constituted a majority of the Empire's inhabitants),

but it became plain that this support was unlikely to be selfless - as can be appreciated by considering this passage from the

Manifesto to the peoples of Europe

issued by the Pan-Slav Congress on the

12th June, 1848:-

We are resolved to maintain the integrity and independence of the empire by every means in our power. We repel all the accusations of separatism, "pan-Slavism", and pro-Russian tendencies which may be brought against us by evil-disposed calumniators.

... Our national independence and our union depend on the maintenance of the independence and integrity of the Austrian empire. The task which we essay is essentially conservative, and there is nothing to cause inquietude to our fair-minded and liberal fellow-citizens of other nationalities".

"In the belief that the powerful spiritual stream of today demands new

political forms and that the state must be re-established upon altered

principles, if not within new boundaries, we have suggested to the Austrian

Emperor, under whose constitutional government we, the majority, live, that he

transform his imperial state into a union of equal nations, which would

accommodate these demands no less fully than would a unitary monarchy.

We see in such a union not only salvation for ourselves but also freedom, culture, and humanity for all, and we are confident that the nations of Europe will assist in the realization of this union. In any case, we resolve, by all available means, to win for our nationality the complete recognition of the same political rights that the German and Hungarian peoples already enjoy in Austria."

We see in such a union not only salvation for ourselves but also freedom, culture, and humanity for all, and we are confident that the nations of Europe will assist in the realization of this union. In any case, we resolve, by all available means, to win for our nationality the complete recognition of the same political rights that the German and Hungarian peoples already enjoy in Austria."

This present page is one of a series treating with themes unfolding during the history of the European Revolutions of 1848.

The content of these pages is not simplistically written but it is hoped that those who last the course will have a good insight as to how eminent historians have come to view these times as being a "turning-point at which modern history failed to turn".

- * This Page * - The European Revolutions of 1848 begin

- A broad outline of the background to the onset of the turmoils and a consideration of some of the early events in

Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest and Prague.

- The French Revolution of 1848

- A particular focus on France - as the influential Austrian minister Prince Metternich, who sought to encourage the re-establishment of "Order" in the wake of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic turmoil of 1789-1815, said:-"When France sneezes Europe catches a cold".

- The "Italian" Revolution of 1848

- A "liberal" Papacy after 1846 helps allow the embers of an "Italian" national aspiration to rekindle across the Italian Peninsula.

- The Revolution of 1848 in the German Lands and central Europe

- "Germany" (prior to 1848 having been a confederation of thirty-nine individually sovereign Empires, Kingdoms, Electorates, Grand Duchies, Duchies, Principalities and Free Cities), had a movement for a single parliament in 1848 and many central European would-be "nations" attempted to promote a distinct existence for their "nationality".

- Widespread social chaos allows the re-assertion of Dynastic / Governmental Authority

- Some instances of social and political extremism allow previously pro-reform liberal elements to join conservative elements in supporting

the return of traditional authority. Such nationalities living within the Habsburg Empire as the Czechs, Croats, Slovaks, Serbs and Romanians,

find it more credible to look to the Emperor,

rather than to the democratised assemblies recently established in Vienna and in Budapest as a result of populist agitation, for the future protection

of their nationality.

The Austrian Emperor and many Kings and Dukes regain political powers. Louis Napoleon, (who later became the Emperor Napoleon III), elected as President in France offering social stability at home but ultimately follows policies productive of dramatic change in the wider European structure of states and their sovereignty.

Other Popular European History pages

at Age-of-the-Sage

The preparation of these pages was influenced to some degree by a particular "Philosophy

of History" as suggested by this quote from the famous Essay "History" by Ralph Waldo Emerson:-

There is one mind common to all individual men...

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Its genius is illustrated by the entire series of days. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. Without hurry, without rest, the human spirit goes forth from the beginning to embody every faculty, every thought, every emotion, which belongs to it in appropriate events. But the thought is always prior to the fact; all the facts of history pre-exist in the mind as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant, and the limits of nature give power to but one at a time. A man is the whole encyclopaedia of facts. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of his manifold spirit to the manifold world.

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Its genius is illustrated by the entire series of days. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. Without hurry, without rest, the human spirit goes forth from the beginning to embody every faculty, every thought, every emotion, which belongs to it in appropriate events. But the thought is always prior to the fact; all the facts of history pre-exist in the mind as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant, and the limits of nature give power to but one at a time. A man is the whole encyclopaedia of facts. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of his manifold spirit to the manifold world.