Cavour & Italian unification

Prior to the first irruption of what developed into French, and European, revolutionary unrest after 1789 the political shape of the Italian peninsula derived in large part from the influence of Papal diplomacy over the previous millennium where the Popes had tended to strongly support the existence of a number of small states in the north of the peninsula such that no strong power might presume to try to overshadow the papacy.

Such political decentralisation may have facilitated the emergence of a number of mercantile city states such as the Florence of the Medicis and the Milan of the Sforzas and to have allowed a scenario where ambitious men such as Cesare Borgia could attempt to establish themselves as rulers of territories won by statecraft and the sword. The burgeoning wealth of these city states, despite much political turmoil, helped to fund that re-birth of classical learning and of artistic expression that is known as the Renaissance.

As time passed some of these mercantile states became reconstituted as Duchies and Grand Duchies. By the mid eighteenth century the north of the Italian peninsula featured a number of such dynastic states together with mercantile republics such as Genoa and Venice. The former Duchy of Savoy meanwhile, originally based on limited territories north of the Alps, had expanded to also include Nice, Piedmont (an extensive territory in the north-east of the Italian peninsula) and the island of Sardinia and was known by its senior title as the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Noble House of Savoy maintained its court at Turin in Piedmont. The kingdom under the sovereignty of the House of Savoy is referred to by historians as Sardinia, Piedmont or Piedmont-Sardinia or Sardinia-Piedmont.

In the settlements to the Napoleonic Wars statesmen, in their efforts to restore political stability to Europe, reconstituted most of the Duchies and Grand Duchies often under rulers drawn from junior branches of the Habsburg dynasty or otherwise under Habsburg Austrian tutelage. Habsburg Austria was awarded sovereignty over Lombardy and over the former Venetian Republic whilst the Republic of Genoa was similarly entrusted to the House of Savoy. The territories of the church that straddled the central portion of the peninsula were again placed under Papal sovereignty whilst to the south the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Sicily and Naples) was restored to a junior branch of the Spanish Bourbon dynasty.

Giuseppe Garibaldi, later famous as an Italian patriotic leader, recorded his introduction to the concept of "Italia" as having taken place during a voyage to Constantinople in 1833.

During the course of this voyage he overheard an argument. A young man had been talking about a secret organisation he had joined - La Giovine Italia - or Young Italy. One of his companions commented dismissively, "What do you mean Italy? What is Italy?" The young man now spoke enthusiastically of a "new Italy ... United Italy. The Italy of all the Italians." Garibaldi recorded that listening to these words he felt "as Columbus must have done when he first caught sight of land". In response to this awakening to the idea of "Italia - Italy" he moved to shake the young man enthusiastically by the hand.

The belief that "Italia" was a desirable possibility can be associated with the change in perspectives that many people, particularly from the more affluent artisan, middle and minor aristocratic classes, underwent after the American and French revolutions away from an acceptance of more purely dynastic patterns of sovereignty and towards aspiration towards "liberal" constitutional, and possibly even overtly republican or national notions of sovereignty.

The central figure in the origin of "Young Italy" was one Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872), who in 1821 in Genoa had witnessed the distress of the "refugees of Italy" who were in the process of fleeing into exile after their failure of their revolutionary efforts at winning reform and, moved by their example, had chosen to devote his life to the cause of Italian independence and unity. In 1827 he was initiated into Carbonari movement and was himself forced into exile in 1831 for revolutionary activity. In exile in the French seaport city of Marseilles, then something of a revolutionary hotbed, he advocated subversive activity "even when it ended in defeat" as a method of developing general "political consciousness." He also began to move away from the philosophy of the Carbonari and subsequently founded Giovine Italia (Young Italy) a movement dedicated to securing "for Italy Unity, Independence, and Liberty."

Mazzini's revolutionary vision extended beyond the limited objective of Italian national unity towards the liberation of all oppressed peoples. He hoped for a new democratic and republican Italy that would lead other subject peoples to freedom and liberty and for a new Europe, controlled by the people and not by sovereigns, that would replace the old order.

Giuseppe Mazzini wrote:-

"The republic, as I at least understand it, means association, of which liberty is only an element, a necessary antecedent. It means association, a new philosophy of life, a divine Ideal that shall move the world, the only means of regeneration vouchsafed to the human race."

After his political conversion of 1833 Garibaldi travelled to Marseilles and enrolled in Young Italy. In February 1834 he was active as a propagandist for Young Italy whilst employed as a sailor in the royal Piedmontese-Sardinian navy, his subversive activities were reported to the authorities and, although he evaded capture by the authorities, was sentenced to death in absentia by a Genoese court. He subsequently spent more than twelve years in exile mostly in South America.

From the 1830's a certain sympathy with the idea of a more politically integrated "Italia" was increasingly exhibited by members of the aristocracy and by members of the more affluent artisan, middle and professional classes in the various states of the Italian peninsula.

Camillo Benso Cavour was born at Turin on the 1st of August 1810 into the old Piedmontese feudal aristocracy. Being a younger son of a noble family social tradition steered him into the army such that he entered the military academy at Turin at the age of ten. On leaving the college at the age of sixteen - first of his class - he received a commission in the engineers. He spent the next five years in the army but he spent his leisure hours in study, especially of the English language. During these years he developed strongly marked Liberal tendencies and an uncompromising dislike for absolutism and clericalism. After the accession to the Sardinian throne of Charles Albert, whom he always distrusted, he felt that his position in the army was intolerable and resigned his commission (1831). Cavour's political ideas were greatly influenced by the July revolution of 1830 in France, which seemed to him to prove that an historic monarchy was not incompatible with Liberal principles, and he became more than ever convinced of the benefits of a constitutional monarchy as opposed both to absolutism and to republicanism. His views were strengthened by his studies of the British constitution, of which he was known to be a great admirer such that he was even nicknamed - " Milord Camillo "

During these times the Austrian statesman Metternich was aware of the implicit challenge posed to the settlements of 1815 by those who supported the the formation of "Italy". In letter of April 1847 to the Austrian ambassador to France he wrote:-

"The word 'Italy' is a geographical expression, a description which is useful shorthand, but has none of the political significance the efforts of the revolutionary ideologues try to put on it, and which is full of dangers for the very existence of the states which make up the peninsula."

In 1847 Cavour was involved in the founding of "Il Risorgimento", a newspaper whose very publication had been facilitated by a recent relaxation of censorship, which became the official voice for the Italian National Movement. He successfully pressed King Charles Albert of Sardinia to grant a constitution to his people [to form a constitutional monarchy]; and in 1848 to battle against Austria as an holder of power in the Italian peninsula. The failure of this military action prompted the king to abdicate in favour of his son, Victor Emmanuel.

Cavour became a member of parliament briefly from 1848 - 1849. Subsequently, he became minister of agriculture, industry and commerce in 1850, finance minister in 1851, and premier or prime minister in 1852.

Contemporaries found it hard to know what to make of Cavour's personality and leave on record impressions of him being both enigmatic and devious. The somewhat brusque and soldierly Victor Emmanuel was prepared to work with Cavour as he seemed to sense that Cavour's talents offered the prospect of extensions of the influence and territory of Piedmont-Sardinia. As Prime Minister Cavour sponsored policies that promoted economic development, allowed some liberalisation in politics, and countenanced reforms that, in ways, compromised the position of the Church. Piedmont-Sardinia had already in 1848 abolished the ecclesiastical courts and introduced civil marriage - policies which had met with the dire protests of Pope Pius IX. Cavour's new measure ordered the closure of some one half of the monastic houses within Sardinian territories.

Cavour hoped to secure the annexation of territories in the north of the Italian peninsula to the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. He regarded the conservatism and power of Tsarist Russia as being a potent limitation on almost any popularly inspired alteration in frontiers anywhere in Europe. The outbreak of the Crimean War between France and Britain on one side and Russia on the other meant that a Sardinian interest was also at stake as a reverse for the Tsar would leave him less able to limit such popularly inspired changes in frontiers. Cavour also hoped to win friends internationally by sending some forces to co-operate with the French and British in a war against the Russian Empire that was prosecuted in the Black Sea region in 1854-6. In association with consenting to Piedmontese-Sardinian participation in the Crimean War Cavour had hoped that the overall situation in the Italian Peninsula would be given a hearing during the post-war international Conference.

For several decades Austria and Russia had been the guarantors of reaction in Europe. Russian intervention in the Hungarian Kingdom in 1849 had been crucial to the recovery of the Austrian Empire. The substantial setback that Russia received in this "Crimean War" and also estrangements that occurred between the Russian Empire and the Austrian Empire, and between the Austrian Empire and the western powers, during the course of the war allowed Cavour much more scope to seek to win gains at the expense of a now somewhat isolated Austrian Empire. This diplomatic isolation was complicated by the Austrian Empire still being distressed by Magyar Hungarian restiveness.

Although a Bourbon monarchy had been restored in France in 1815 at the close of the Napoleonic wars it did not endure. The "legitimist" Bourbon line, disliked for their absolutist tendencies, were replaced in an 1830 revolution by the more junior "Orléanist" branch of the dynasty who consented to rule as "Kings of the French" rather than as "Kings of France". Futher revolution in 1848 saw the Orléanist King abdicate, the French kingdom being replaced by a republic to which one Louis Napoleon, a nephew of Napoleon I (i.e. Napoleon Bonaparte), was elected president. By 1852 Louis Napoleon contrived to overthrow the Republic in the name of order, and styled himself, with the consent of the French electorate, as the Emperor Napoleon III of France.

(Napoleon II being a complimentary titled posthumously imputed to Bonaparte's son from a 'marriage of state' that Napoleon I at the height of his political power had entered into with a daughter of the Austrian Emperor. This son, in his infancy, was the heir presumptive to the extensive empire established by his father and had been styled as the 'King of Rome'. Following on from Napoleon's defeated by a coalition of powers this son, a young man of some promise by all accounts, had been raised as an Austrian princeling under the supervision of Metternich but had died of tuberculosis in his early twenties.

As his life ebbed away this young Duke left the great ceremonial sword of honour he had inherited from his father not to any of his surviving Bonaparte uncles but to his cousin Louis Napoleon).

Napoleon III had, of his own volition, ideas of intervening in that Italian Peninsula where his uncle Napoleon had been so active in events. Napoleon, in exile on the remote island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, had left written records that characterised one of the main planks of his policy as Emperor as being that of the championing of states based on nationality. Whilst this is probably a sanitised version of what Napoleon did in what were more truly efforts to extend and preserve the power of his empire Napoleon III considered that European peace would in the long run be promoted by the establishment of states based on the "National Principle". Napoleon III was famously on record as having said that he "would like to do something for Italy." As a Bonaparte with the Bourbons restored to the French throne Louis Napoleon had had an interesting earlier life outside France and had actually been active as a member of the Carbonari secret society (which sought to win liberal, constitutional, and national reform) in the Papal States and elsewhere during the turmoil of 1830-1831 during which his own older brother had lost his life from disease and during which his own life was also similarly in grave peril.

After the recovery of Austrian power in the Italian peninsula in 1849 Paris became a city of exile for many persons who had been prominent in "Italian" nationalistic and republican agitation in 1848-9. One such person, Daniele Manin, who had been the leader of the Venetian Republic in defiance of Austria during 1848-9, signalled a conditional acceptance of Italian monarchy in the Italian peninsula in a statement addressed to Victor Emmanuel II which appeared in the Italian Republican press in September 1855.

"If regenerated Italy must have a king, there must be only one, and that one the king of Piedmont ... Convinced that before everything else we must make Italy, as that is the principal question, superior to all others, it (the republican party) says to the House of Savoy: 'Make Italy and I am with you. If not, not."

The sympathies of many in the Italian peninsula who were supportive of a more politically integrated "Italia" found a potent leadership after July 1857 when Manin, a Lombard nobleman named Giorgio Pallavicino, and a Sicilian named Giuseppe La Farina founded the National Society. This society hoped to achieve "the marriage of the Italian insurrection to the army of Piedmont" and took as its slogan "Unity, Independence, and Victor Emmanuel" in the hope that monarchists, federalists, liberals and also those disenchanted with Mazzini's hitherto unavailing leadership of "Italian" republicanism could unite under a common cause.

Manin, Pallavicino and La Farina were offering their support towards the "Making of Italy" rather than the "Aggrandization of Piedmont".

In January 1858, in a dramatic instance of "politically motivated" violence in Europe, an Italian, Count Orsini, and a band of followers were responsible for eight persons being killed and for some one hundred and fifty persons being injured during an explosive attempt on the life of the French Emperor during a visit to the Opera. Orsini, who had earlier been prominent in the Roman Republic that had briefly been established as a result of the turmoil of 1848, now intended to encourage opportunities for reform in the Italian Peninsula by provoking turmoil in France (and more widely in Europe) through the assassination of Napoleon III and expected that subsequent disruptions would probably produce change in the Italian Peninsula that would leave it less under Austrian rule and more liberally governed. Orsini was executed for his crimes in March 1858 but left behind him a testament depicting Napoleon III as an incarnation of the spirit of reaction.

This attempt on the life of Napoleon III was in fact the fourth such attempt by a person "patriotically" committed to forcing change in the Italian Peninsula.

Napoleon III decided to become more deeply involved in developments there - partly in the hope of lessening the likelihood of yet further attempts on his own life and also partly in the hope of adding lustre to his then failing appeal in France through a domestically impressive foreign policy initiative that could lead to French influence replacing that of the Austrian Empire in the north the Italian peninsula.

A pattern of indulgence in complex and devious diplomatic agreements, in the unscrupulous use of force, and of the exploitation of populist sentiment in the interest of the dynastic state, of that type which later came to be called Realpolitik, (tr. practical politics), had an early demonstration after the Crimean War in policies followed by Cavour as the Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia. Cavour sought some form of alliance with the French against Austria in the hope of ensuring that some of those areas of the Italian peninsula ruled directly by Austria, or by Austrian supported rulers, would be more free to join in with a redrawing of the political map of the the Italian Peninsula. Cavour, at this time, seems to have been intent on achieving the integration of several territories in the north of the peninsula into an extended Piedmontese-Sardinian state rather than upon a political transformation of the entire peninsula.

In May 1858 a Dr. Conneau, a close friend of Napoleon III, visited Turin and made a point of 'advising' Cavour that the French Emperor would soon be spending several weeks at the French resort of Plombières, this town being located in the Vosges region fairly close to the frontiers of the territories of the House of Savoy!!!

At a subsequent shadowy meeting in July 1858 between Napoleon III and Cavour, (who was supposed to be on route to holiday in Switzerland with some time being spent inspecting railway construction in Savoy!!! ), the possibility of France gaining territories on the French side of the Alps from Piedmont-Sardinia in return for assistance in reshaping the map of Italia was mooted. Savoy was a particular object of French desire, it had been annexed to France during the revolution, and was held to be within the "Natural Frontiers" of France.

A principal ambition of Napoleon III as Emperor of France was to achieve the overthrow of some aspects of the settlement made in 1815 at the close of the Napoleonic wars, as these settlements were seen as placing irksome limits on France. The French annexation of Savoy would of itself constitute a breach of the 1815 settlement.

An informal Pact of Plombières envisaged Piedmont-Sardinia annexing Lombardy - Venetia and further envisaged the entire Italian Peninsula participating in a Confederation with the Pope as its figurehead. France agreed to support Piedmont-Sardinia militarily against the Austrian Empire. Napoleon III stipulated that any such conflict should be "non-revolutionary", and should be justifiable in the eyes of the world - neither Piedmont-Sardinia nor France should seen as instigators.

In December 1858 Odo Russell, a British diplomat usually based in Rome, was informed by Cavour at an interview in Turin, that he, Cavour intended to force Austria to declare war. Cavour even went so far as to predict that this would happen "about the first week of May".

On 1 January 1859 Napoleon III, at his New Years Day reception, publicly expressed to the Austrian Ambassador his regret - "I am sorry that our relations are not so good as I wish they were, but I beg you to write to Vienna that my personal sentiments for your Emperor are unchanged". This public notice of dissatisfaction was taken up by wider society - fears of hostilities affected the stock markets.

In these times Cavour prepared a speech which it was intended should be delivered to the Italian parliament by King Victor Emmanuel. Draft copies of this speech were sent to King Victor Emmanuel and to Napoleon III for their approval and, after these were returned to Cavour with some amendments by the King and Napoleon III, Cavour himself had an opportunity to make further deletions and additions during the process of translating the draft into Italian, the result was that on the 10th of January King Victor Emmanuel appeared before his parliament and, as part of his speech declared "While respecting treaties we cannot remain insensitive to the cry of suffering that rises towards us from so many parts of Italy." This sentence could not be expected to go down too well in Austrian circles.

Towards the end of January the understandings agreed between France and Piedmont were formalised through the signing of an "offensive-defensive" alliance. In line with the wishes of Napoleon III Cavour took steps that were designed to ensure that the conflict would seem to have been started by Austria. To this end Cavour arranged for a crisis to be raised where subjects of the Duchy of Modena, where the ruler was known to be supported by Austria, were encouraged by Cavour to express dissatisfaction with the current administration and to invite Victor Emmanuel to come to their aid. On the 23rd of April Cavour was intercepted on the steps of the Chamber of Deputies by two Austrian officers who handed him a note from their Emperor in which Austria demanded the demobilisation of the Piedmontese forces; and if a satisfactory answer was not received within three days the Emperor Francis Joseph would "with great regret, be compelled to have recourse to arms to secure it."

Cavour was well pleased with this development and although he told the Austrians to come back in three days for his answer he had no intention to provide such an answer as would deter the Austrian Empire from military action.

When active hostilities did occur the Piedmontese-French interest prevailed.

During this time of conflict there were revolts, motivated by the "Italian" outlook of the National Society, in several Italian states that featured demands for closer political association with Piedmont-Sardinia. If these closer political associations took place Piedmont-Sardinia potentially stood to gain sway over more territory than was envisioned for the North Italian Kingdom mooted at Plombières and might become so powerful as to impede French influence in the Italian Peninsula. The unanticipated revolts in several Italian states also had the potential to compromise the position of the Papacy in ways that would be unacceptable to the powerful Roman Catholic interest in France. In more northerly parts of Europe the Prussians seemed to be engaged in military manoeuvres that might threaten the French interest - Prussia as a member of the German Confederation was obliged to assist in the defence of Austria, as a fellow member of the confederation, should her core territories come under threat. The French had suffered much loss of life in two hard fought battles and the Austrian forces had withdrawn into the inherently formidable "Quadrilateral" of fortresses. Napoleon III drew back from his pact with Piedmont-Sardinia and an armistice of Villafranca, concluded in early July between France and Austria without consultation with Sardinia, formally consented only to Lombardy entering upon a close political association with Piedmont-Sardinia stating that several of the states that had experienced revolts should be restored to their former rulers. That is to say that Austria agreed to cede Lombardy not to Piedmont, but to Napoleon III, from whom Victor Emmanuel would then receive it.

Victor Emmanuel felt obliged to accept the situation resulting from the reluctance of Napoleon III to continue as an active ally but Cavour protested in an intemperate fashion and even resigned his post as Prime Minister after explicitly accusing Victor Emmanuel of betrayal.

In the event local plebiscites ensured that Modena, Parma, Tuscany, and the Romagna (i.e. the Papal 'Legations' of Bologna, Ferrara, Ravenna and Forli), where assemblies had voted for close political association with Piedmont-Sardinia, were indeed associated with the Sardinian Kingdom.

Assurances offered during the campaign prior to the holding of these plebiscites that these territories could hope for a degree of regional autonomy were not subsequently honoured.

A particularly keen problem arose from the fact that the Romagna was a longstanding, if restive, part of the territories of the Church - and the Church could only view its alienation from their control as a profoundly intolerable challenge both to itself as such and to its legitimate, indeed divinely ordained, traditions of temporal sovereignty. From the point of view of the Papacy the longstanding territories of the church were "God given" and were as such held in trust by the Popes on behalf of the Catholics of the entire world.

Napoleon III pressed for plebiscites to take place in Savoy and Nice in the hope that these territories would agree to come under French sovereignty, as his price for consenting to Piedmont-Sardinia gaining territory in the Italian peninsula.

Cavour and Victor Emmanuel had shown themselves prepared to exploit Italian Nationalist sentiment in pursuit of annexations of territory to Piedmont-Sardinia. Savoy and Nice were dear to Italian sentiment, indeed Garibaldi, one of Italian Nationalism's populist leaders was actually a Nizzard and was less than pleased by Nice becoming French. Garibaldi actually sent an associate to King Victor Emmanuel to bluntly inquire if it was true that Nice had been ceded to France and asking for an answer "yes or no".

In reply Victor Emmanuel, whose dynasty had originally held territorial sovereignty as the Dukes of Savoy, insisted that Garibaldi be advised that not only Nice but Savoy also had been ceded. "And if I can reconcile myself to losing the cradle of my family and my race he can do the same."

By the spring of 1860 perhaps a third of what was thought of as "Italian" territory was now under the Kingship of Victor Emmanuel. Similarly about one half of the "Italian" people, some 11,000,000 persons, lived within the Kingdom ruled by Victor Emmanuel. Garibaldi would actually have preferred that there should be an Italian Republic but on balance fell in with the establishment of an Italian Kingdom. This acceptance was based on the practical usefulness of Piedmont-Sardinia as a focus of military power capable of challenging the Austrian Empire.

In late March 1860 elections were held to return an "Italian" parliament which was to convene in early April in King Victor Emmanuel's capital city - Turin.

As part of his first speech to the new parliament King Victor Emmanuel spoke of Italy:-

It is no longer the Italy of the Romans, nor that of the Middle Ages; it must no longer be the battle-field of ambitious foreigners, but it must rather be the Italy of the Italians".

In relation to Savoy and Nice King Victor Emmanuel spoke of the necessity of some sacrifice "for the good of Italy" even though the relinquishment of these territories "cost my heart dear".

Garibaldi actually planned to intervene in Nice in the hope of disrupting a plebiscite that was intended by the French authorities to endorse the transfer of Nice to France but was prevailed upon to reconcile himself to the alienation of his personal homeland and to involve himself instead in an ongoing Sicilian revolt. To this end Garibaldi applied to Cavour for the supply of large quantities of firearms which he subsequently received, with Cavour "turning a blind eye", from the National Society.

In early May Garibaldi led a seaborne expedition from Genoa, some one thousand strong (and of a wide range of ages), to Sicily. Notwithstanding his effective co-operation in the supply of firearms Cavour publicly opposed this expedition, by Garibaldi, to the south. Units of the Sardinian navy meanwhile, were ordered to provide a discrete "escort" to the expedition.

Cavour was quite prepared to see Piedmont-Sardinia play as full a role as possible in any Confederation of Italian States and would actually have been content with the probably future of Piedmont-Sardinia, with its recent additions of territory, as a free and constitutional state and might not have not sought to risk what had been achieved by looking yet more of Italia to be integrated with Piedmont-Sardinia. A major worry being that too great a growth in the potential power of Piedmont-Sardinia, or too great a challenge to the power or sovereignty of the Papacy being offered, could well lead to foreign intervention in events. Nevertheless Cavour found it politically impossible for a variety of reasons to actually prevent the expedition. Garibaldi for his part, and to the disgust of some avowed republicans amongst the Thousand, announced that the expedition's war-cry would be "Italy and Victor Emmanuel."

The plebiscites held in Savoy and Nice did seem to yield majorities in favour of annexation to France but allegations were widely made that this outcome was engineered to achieve the result required by the agreements between Cavour and Napoleon III.

"Garibaldi and the Thousand" disembarked at Marsala in Sicily on 11 May where Sicilians in revolt against King Francis II welcomed this arrival.

In August with Sicily almost completely won from the control of Francis II Garibaldi decided to carry the revolt to the Neapolitan mainland and his forces were joined by many persons variously committed to challenging Bourbon rule or to securing further changes in the overall situation of the Italian Peninsula. The armies of Francis II proved unable to prevent the city of Naples from falling to the effective control of Garibaldi by early September.

Garibaldi hoped to present the territories that he and his followers had won to the Kingdom of Italy but intended that those territories should include the city of Rome where, incidentally, "Italian" enthusiasm was increasingly evident.

As news of Garibaldi's successes filtered north and word arrived from France assuring him of non-interference, Cavour felt able to call the exploits of Garibaldi and his followers as "the most poetic fact of the century". That being said Cavour feared that an attack on Rome by Garibaldi would lead to French intervention in support of the continued Temporal Power of the Papacy. Cavour also considered that Garibaldi and Mazzini might attempt to set up a Republic in the South of Italy.

Cavour and Piedmont had hitherto "led" and "controlled" the movement towards "Italian" territorial integration - future marked successes by Garibaldi's irregular forces had the potential to somewhat compromise Piedmontese-Sardinian perceived leadership of events.

Cavour arranged for some unrest to take place within Umbria and the Marches (territories of the Church to the south of the Romagna) as a cover for the movement of a Piedmontese-Sardinian army into these Church territories "to restore order." In mid September the Piedmontese-Sardinian army proceeded southwards, through some of the territories of the Church, in order to meet with and dissuade an assault on Rome by Garibaldi. During the course of moving across the territories of the Church the Piedmontese-Sardinian forces clashed with forces recently formed in the service of the Pope but were not thereby prevented from proceeding south. The Piedmontese-Sardinian forces could not have been prevented, but voluntarily refrained, from advancing on Rome at this time.

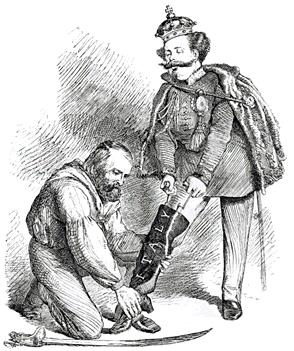

Caricature of Victor Emmanuel's leg filling the 'boot' of Italy with the aid of Garibaldi! :-

When the Piedmontese-Sardinian force met up with Garibaldi at Teano in the Kingdom of Naples on 26 October Garibaldi effectively surrendered his gains to Victor Emmanuel with a handshake and called upon his men to salute Victor Emmanuel:- "Hail to the first King of Italy." They responded positively :- "Viva, il Re!" Some local peasants who gathered shortly thereafter were however far more ready to cheer Garibaldi himself as their liberator rather than to enthuse over their unlooked-for new King.

As an outcome of these developments there were annexations of territory to Piedmont-Sardinia after plebiscites in Sicily, Naples and Umbria and the Marches. Astute observers held that, in the cases of Sicily and Naples, the positive vote in favour of association in the Italian Kingdom was, in part, due to there being no more locally acceptable alternative put on the table for endorsement.

Sicily had long seen itself as being an unwilling colony of Naples and had a tradition of separatist aspiration - the fact that the earlier stages of the most recent uprising against Bourbon rule in Sicily had also featured a strong socio-political challenge by the local peasantry directed against the Sicilian propertied classes caused many influential Sicilians to discount separatism and to look to Victor Emmanuel and nascent "Italy" as offering some potential support against future socio-political unrest. Cavour's agents (not above stimulating demonstrations against Garibaldi's government) gained support for annexation from middle and upper class groups petrified at the danger of rural and urban insurrection. When a plebiscite took place in October annexation won by an overwhelming margin. A barely imagined Italy became a reality as the outcome of a complex game of class conflict, fear, ambition, uncertainty, and military force. What had begun as a home-grown popular insurrection and democrat-led guerrilla warfare ended as an effective royal conquest supported by the island's social elite under the guise of a well-managed plebiscite.

Garibaldi, for his part, voluntarily withdrew from the scene returning to his island home of Caprera ostensibly to resume life as a cultivator of the soil and livestock farmer.

Victor Emmanuel was proclaimed as King of Italy "by the grace of God and the will of the people" by an Italian Parliament in session in Turin in March, 1861. Cavour made speeches in which he asserted that Rome was the only Italian city to which all others could yield precedence and that, as such, Rome must become the capital of Italy. He held however, that this accession to Rome must be by moral means with the assent of the Papacy itself and of France. Cavour further envisaged that with Rome as the Italian capital the Papacy would not exercise temporal power and that there would be a separation of church and state. A "Boncompagni" bill, approved by the chamber of deputies shortly thereafter recognised Rome, still garrisoned as it was by French soldiers in support of the traditional Papal position, as the capital of Italy.

Massimo D'Azeglio, Cavour's predecessor as prime minister of Piedmont-Sardinia suggested, in the first meeting of the parliament of the newly united Italian kingdom, famously suggested that "Italy is made, We still have to make Italians." Many wealthy people had some knowledge of French and of the Florentine-Tuscan "Italian" dialect established through the works of Dante and others as a literary language. Most people spoke regional dialects that were often unintelligible in other parts of the Italian peninsula.

The historic linguistic diversity of the Italian peninsula had come to be seen as being something of an obstacle to the fulfilment of Italian-National aspirations. "Even in Piedmont, difference of language is our great difficulty: our three native languages are French, Piedmontese and Genoese. Of these, French alone is generally intelligible. A speech in Genoese or Piedmontese would be generally unintelligible to two-thirds of the Assembly. Except the Savoyards, who sometimes use French, the deputies all speak in Italian; but this is to them a dead language, in which they have never been accustomed even to converse. They scarcely ever, therefore, can use it with spirit or fluency. Cavour is naturally a good speaker, but in Italian he is embarrassed. You can see that he is translating; so is Azeglio; so are they all...

From a letter by Marchioness Arconati to Nassau William Senior, 6th November 1850 A dynastic "House of Savoy" ruled in Piedmont where it upheld, linguistically, a principally French and Piedmontese court and administration despite having originated north of the Alps in the Duchy of Savoy (where there was a Savoyard dialect!).

This House of Savoy had become a Royal House when in 1713, by a treaty of Utrecht, one of its Dukes, Victor Amadeus II, was recognised as being King of Sicily, (later, i.e. 1720, exchanged for Kingship of Sardinia), as a reward for his co-operation in widespread turmoil over dynastic succession elsewhere in Europe but had continued with its French and Piedmontese court and administration based on Turin in Piedmont.

Thus late-nineteenth century Risorgimento "nation building" in the Italian peninsula, as keenly supported by the rising middle class and artisan would-be "Italian" political nation, occurred against a background of the historic existence of many languages and dialects including French, Piedmontese, Genoan, Sicilian, Sardinian and Ligurian. The processes of "making Italians" ultimately included an acceptance of Florentine-Tuscan "Italian" as the desired official language of the newly unified state.

Quite apart from linguistic issues there were also problems of establishing a shared "Italian" civic consciousness and identification against the background where the multiplicity former states had been mainly been administered by reactionary statesmen and clerics and where the majority of the people had lived materially impoverished rural lives.

The population of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 was some 22 million, of whom 8 million lived in the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and of whom 17 million were illiterate. Due to restrictive clauses in the Statuto constitution only about one-half million persons were eligible to vote, and of that half million only 300,000 actually voted.

Italian sentiment had its own opinion as to what constituted Italian territory and in 1861 the most notable territories which Italian nationalism could regard as being "Italia Irredente" (i.e. Unredeemed Italy - hence irredentism) were Venice and Rome.

Venice, (where there was a strongly established Venetian dialect), was under the control of the powerful Austrian Empire and unlikely to become easily available to Italian annexation. Cavour warned the Italian parliament that Italy could not make war on Austria single-handed, he still hoped that Venice would be joined into Italy but told the chamber that it was a "secret of providence" whether such a "deliverance" would come "by arms or diplomacy".

The former King Naples and Sicily in these times was living in exile in Rome and followed a policy of somewhat encouraging "brigandage" in Naples and Sicily in the hope that it would facilitate his own return to the throne of the Two Sicilies. The Italian kingdom had to keep tens of thousands of troops in the south in efforts to firmly maintain order and stamp out such "banditism".

A French army still defended Rome in the Papal interest. The French forces present in Rome attempted police action against groups, based in the Roman territories, that were actively engaged in such disruptive endeavours to the south in formerly Neapolitan territory. The French were however obliged to hand over any persons so arrested to the Roman authorities - it appeared to the French commanders that there own efforts in this regard were frustrated by the Roman authorities tending to release such prisoners to once again attempt to cause disruption in the south.

France had a long tradition of European power and had long history or regarding itself as being the "Eldest daughter of the Church". Napoleon III in his own day found himself on the horns of a dilemma: if he abandoned the Pope he would incur the enmity of the French Catholics, if he protected the Pope he would thwart Italian patriotism. He himself once famously said that "the occupation of Rome will be the mistake of my reign". In a letter of June 1859 to the French diplomatic representative in Rome Napoleon III had written:-

"There can exist no contradiction between my words and my actions. I wish for the independence of Italy, but I must maintain the authority of the Pope in which one hundred and fifty million of consciences are interested; and I am resolved to maintain order in Rome."

In the case of Rome matters were thus complicated by intangible but telling considerations. Whilst many Italian nationalists might consider that "without Rome for its capital Italy cannot be constituted" it was also the case that sincere Roman Catholics in Italy and beyond regarded the Temporal Sovereignty of the Popes as being beyond question.

It was held that much of the territories over which the Papacy was Temporally Sovereign had been awarded to the church centuries previously by such renowned Emperors as Constantine and Charlemagne and it was also held that it was inherently most undesirable that the head of the Church should be the subject of any Temporal Prince.

In parliamentary speeches of late March, 1861, Cavour had uttered such sentiments as:-

..."the reunion of this great city to the rest of Italy must not be interpreted by the great mass of Catholics in and outside Italy as the sign of the Church's servitude. That is, we must go to Rome, but the true independence of the Pontiff must not be lessened. We must go to Rome, but civil authority must not extend its power over the spiritual order...

...We believe that the system of liberty has to be introduced into all aspects of religious and civil society ... we believe it necessary for the harmony of the building we wish to raise that the principle of liberty be applied to relations between Church and State."

Cavour, in these times, through intermediaries, attempted to negotiate the voluntary inclusion of the Roman territories into the Italian state he was attempting to construct. He offered a recognition of a nominal papal sovereignty over all papal territories in a situation where King Victor Emmanuel would, however, have "exercise of the government."

Guarantees over the income of the church, its freedoms from taxation, and of a respected position for the church were also offered.

In the event negotiations were broken off early in 1861 after the pope refused to exchange his temporal power for any guarantee of independence saying:- "This corner of the earth is mine. Christ has given it to me. I will give it up to him alone."

Count Camillo Benso de Cavour died of natural causes in early June 1861.

In 1862 in a manner reminiscent of the way "Garibaldi and the Thousand" had proceeded to Sicily some two years previously a force again led by Garibaldi unsuccessfully attempted to win more territory for Italy by assailing Calabria then part of the remaining territories of the Church.

Alongside the earlier anti-Clerical measures passed by the former Kingdom of Sardinia relations with the Papacy had not been improved by a forced sale in 1859, in the cash strapped Sardinian states interest, of monastic lands.

The Papacy and Cardinal Antonelli continued to hope for the restoration of Romagna, Umbria and the Marches to Papal Sovereignty. They refused to consider reform of the administration of the remaining territories of the church until such a restoration was brought about.

In the mean time Britain had been the first foreign power to extend recognition to the Italian Kingdom. By mid 1861 France had also offered recognition to the Kingdom of Italy whilst officially deploring that Kingdoms retention of church territories, By mid 1862 those supportive of a restitution of Romagna, Umbria and the Marches to Papal Sovereignty were discomfited by the further recognition of the Italian Kingdom by Russia and Prussia. The King of Portugal, meanwhile, entered into marriage with a daughter of King Victor Emmanuel. This marriage took place despite the fact that, in 1860, King Victor Emmanuel had actually been pronounced to be excommunicated because of his "Italian" policies!!!

Napoleon III did not really relish his role as protector of the traditional Papal sovereignty over Rome and its environs - yet had he not sought to fulfil this role it would lead to serious consequences in terms of relations with the powerful clericalist support his government enjoyed in France. In an attempt to lessen the awkwardness of his position he entered into an agreement, without the consent of the Papacy, with the Italian Kingdom known as the Convention of September whereby Italy would herself guarantee the Papal territories against attack and Napoleon III would withdraw the French garrison within two years. It was accepted that the Pope could recruit an army of ten thousand from the catholic countries of Europe in the interests of the security of the territories of the church. A secret clause endorsed the transfer of the seat of the Italian government away from Turin to Florence within six months.

As French control of Savoy gave them unrestricted access to certain key Alpine passes the recent cession of Nice and Savoy had in any case left Turin somewhat strategically vulnerable from the north-west. There was serious rioting in Turin, involving some fifty fatalities, when the news of the relocation of the seat of government was announced. The population there could, after all, depict itself as having contributed very greatly to the move toward Italian Unification. This move did seem however to let Napoleon III out of his difficult position as protector of the Papacy and to allow the French an opportunity, from their own point of view, to depict the Italian Kingdom as having decided upon a new and long term capital.

Late in 1864 Pope Pius IX, having become increasingly convinced that modern secular ideas presented a real threat to the Church issued an Encyclical of Papal Letter to which was attached a "Syllabus of Errors" which condemned "the principal Errors of our time." The Syllabus is a series of Articles that condemned some ninety "errors and perverse doctrines" including rationalism, science, democracy, the liberty of the press, secular education, socialism and communism.

The last, eightieth, Article of the Syllabus stigmatized as an error the view that "the Roman Pontiff can and should reconcile himself to and agree with progress, liberalism, and modern civilization."

Many in northern Europe and North America seemed to take the Syllabus to be indicative of obscurantism but most Italians understood many of the Errors to be presented as a none too oblique condemnation of the Italian Kingdom.

During these times the Kingdom of Italy offered to purchase Venetia from the Austrian Empire. This, substantial, offer was refused by Francis Joseph under the advice of the military party at his court who suggested that such a transfer would be contrary to Austria's honour.

Prussia continued to pursue its longstanding rivalry with Austria for predominance in "the Germanies". In April of 1866, against a complex European diplomatic background, the Italian government entered into a Treaty with Prussia by which Italy hoped to gain Venetia from Austria. Although the Austrians themselves subsequently offered Venetia to the Italian Kingdom in return for mere neutrality the Treaty with Prussia was maintained.

The policy makers of the Kingdom of Italy may have hoped to secure other areas of perceived "Italia Irredente - Unredeemed italy") such as Trentino (with Alto Adige or South Tyrol) and Venezia Giulia (a territory that included Trieste - a notably important seaport) in addition to Venetia as a result of direct "Italian" involvement. Both Trentino (with Alto Adige or South Tyrol), partly inhabited by ethnic Germans, and Venezia Giulia, partly inhabited by ethnic Slovenes, were northern borderlands then under fairly direct Austrian Habsburg sovereignty. The policy makers of the Kingdom of Italy may have hoped for a sincere, if reluctant, relinquishment of Venetia, Trentino, and Venezia Giulia, by an Austrian Empire that had been checked in war and considered that Italian opposition would help to ensure that such a check was delivered. The policy makers of the Kingdom of Italy may also have thought that the new Kingdom of Italy should actually fully stand by its treaty obligations such as it had entered into with Prussia.

A "Seven Weeks War" was subsequently contested in the summer of 1866, while "Italian" forces did not make much headway themselves the Italian Kingdom benefited from the way in which Prussian forces overcame those of Austria, and Venetia, which had been formally ceded to Napoleon III by Austria, was given to Victor Emmanuel II, in much the same way as Lombardy had been transferred and was incorporated into the Italian Kingdom. This incorporation was overwhelmingly endorsed by the result of a plebiscite in Venetia.

After hearing this result Victor Emmanuel said...

"This is the finest moment of my life; Italy is made, but it is not completed."

This statement being interpreted as suggesting that the Kingdom of Italy had "unfinished business" in relation to her hoped for capital - Rome!!!

A French

army returned to defend Rome early in 1867 after Garibaldi and a large force

made a serious armed incursion into these territories from

Tuscany. The incursion was opposed by forces, drawn from many

Catholic countries, in the employ of the Papacy. This incursion may

have had the covert personal support of the King Victor Emmanuel who hoped

that the remaining Church territories might fall to the Italian kingdom if

Garibaldi prevailed.

As the Franco-Prussian War irrupted in 1870 Napoleon III was obliged

to recall those forces garrisoned in protection of Rome in order

to defend France herself on 16 August 1870. The Convention of September 1864 with France by which the Italian

Kingdom had offered to guarantee the security of the territories of the Church had not in fact been in operation

as France had again felt obliged to undertake responsibility for security after Garibaldi's campaign of 1867 -

given the French withdrawal to meet the Prussian challenge it now came back into operation. The Convention

contained a phrase that read

"in the case of extraordinary events both of the contracting parties would resume their freedom of action."

Given the absence of the

French and more particularly the fact of the Prussian led

interest prevailing in the wars after the critical battle of Sedan on 2 September the Kingdom of Italy was

largely obliged by the strength of "Italian aspiration" to deem the Prussian victory an "extraordinary event" and

to seriously consider a move to

annexe Rome and the remaining Papal territories.

On 7 September several Great Powers of Europe were advised by Italian diplomatic channels that Italy

intended to take control of Rome but would thereafter support the continued freedom and spiritual independence of

the papacy. There was no significant protest from any of the these powers as they seemed to accept that it was now

inevitable that the Italian Kingdom would move to annexe Rome.

King Victor Emmanuel appealed to Pope Pius IX for a voluntary

acceptance of the protection of the Kingdom of Italy in the "name of religion and peace."

An envoy was sent to the Pope with a

personal letter, dated 8 September 1871, from

Victor Emmanuel who styled himself as writing "With the affection of a son, the faith of a Catholic, the loyalty

of a king

and the soul of an Italian" outlining that his soldiers were obliged to cross the papal frontiers to

maintain the security of Italy and of the Holy See. Assurances were given in this letter that

"the Head of Catholicity, surrounded by the devotion of the Italian people, should preserve on the banks of the Tiber

a glorious seat independent of human Sovereignty".

On 11 September the Pope replied saying that he could not admit the demands of Victor Emmanuel's letter nor accept

the principles contained therein.

Some sixty thousand soldiers in the service

of the Kingdom of Italy subsequently moved to seize the Papal territories. The Pope invited

the numerous diplomatic representatives that were present in the Vatican

to bear witness to this assault and delivered protests to them that

were to be conveyed to their authorising governments.

The

walls of Rome were compromised after a four hour bombardment on the 20th September, 1870. Some nineteen

papal soldiers and forty-nine Italian soldiers lost their lives in the associated battle. This "token"

battle was itself brought to an end by the Papacy ordering its defenders to lay down their arms after making

a show of resistance consistent with honour. The

subsequent annexation of Rome to the Italian Kingdom was resoundingly endorsed by a

plebiscite held two weeks later. Rome was now proclaimed as the capital of the Italian

kingdom. There was in fact some debate about the wisdom of this move of the Italian capital away from Florence but

it seemed that no other designation would be acceptable to the Romans themselves.

Pope Pius IX was offered numerous far-reaching assurances as

to the position of the Papacy in a "Law of Guarantees" considered by

the Italian Parliament meeting in Florence in January 1871 and passed into law in May 1871. These guarantees would have

recognised the Pope as being a Temporal Sovereign with the

Vatican and Lateran palaces being deemed to be outside Italian

territory and with a large grant equal to previous Papal budgets

being made.

Pope Pius and Cardinal Secretary of State Antonelli chose to ignore such a system of guarantees

and, when the first

installment of monies

were offered they were repudiated by Pope Pius :- "Never will I accept it from you by way of reimbursement and

you will obtain no signature which might seem to imply an acquiescence in or a resignation to Spoilation."

In June 1871 the Rome became the Italian seat of government and King Victor Emmanuel delivered an address

to the parliament of the

Kingdom of Italy now convened in Rome. This address begins:-

Senators and Deputies, gentlemen:

The work to which we consecrated our life is accomplished. After long trials, Italy is restored

to herself and to Rome. Here, where our people, after centuries of separation, find themselves for the first

time

solemnly reunited in the person of their representatives; here where we recognise the fatherland of our

dreams, everything speaks to us of greatness; but at the same time it all reminds us of our duties.

The joy that we experience

must not let us forget them...

...We have proclaimed the separation of Church and State. Having recognized the absolute independence

of the spiritual authority, we

are convinced that Rome, the capital of Italy, will continue to be the peaceful and respected seat of

the Pontificate...

A Papal Encyclical that was sent to the higher Roman Catholic clergy

in May 1871 had included the following sentiments:-

...it must be clearly evident to all that the Roman Pontiff, if he be subjected to

the dominion of another prince and is no longer actually in possession of sovereign power

himself, cannot escape (whether in respect to his personal conduct or the acts of his

apostolic office) from the will of the ruler to whom he is subordinated, who may prove to

be a heretic, a persecutor of the church, or be involved in a war with other princes. Indeed, is not

this very concession of guarantees in itself a clear instance of the imposition of laws upon us, - upon

us on whom God has bestowed authority to make laws relating to the moral and religious order, - on us

who have been designated the expounder of natural and divine law throughout the world? ...

Pope Pius IX had already depicted Rome as being "in the possession of

brigands" after "the triumph of disorder and the victory of the most perfidious revolution" and had

styled himself as being the "Prisoner of

the Vatican." He insisted on referring to the "usurping" power as a Sub-alpine, rather

than an "Italian"

government. Decades of deep estrangement between

Italy and the

Papacy ensued. Pope Pius forbade participation by way of voting

or any political involvement in the workings of the "godless"

Sub-alpine government.

Quite apart from these tensions between Papacy and Kingdom the new state had other hurdles to face. The

census of 1871 showed that only 2.5% of the 26.8 million population actually spoke the Florentine-Tuscan "Italian"

that was to become the language of the state. Also at this time 69% of population were illiterate but this

is perhaps largely explicable by the fact that

perhaps 60% of the people worked as subsistence farmers on the land and that there had previously been no

widespread

sponsorship of general education by the church or by the states that had so recently been replaced by

the new Italy. The disparity of prosperity between the relatively prosperous north and relatively impoverished

south continued as a worrisome factor for many years thereafter.

The Kingdom of Italy that emerged after 1870 was not the dynamic, powerful state that

many nationalists had hoped for.

The state was mired in debt. The liberal values of the regime suggested that they assume

the debts of the states that Piedmont-Sardinia had absorbed in the process of unification. The wars

of liberation had been expensive. The loans organized in France had to be repaid. Much

infrastructure for a united state had to be created: public buildings in Rome, the new

capital, a navy, a unified army, and an educational system, to name a few.

Italy was poor, since its establishment in 1861 the Italian kingdom had experienced great difficulty

in balancing its budgets and the liberal, Piedmontese, administrators of the Kingdom of

Italy insisted on financial responsibility.

In the south there was much brigandage and insurrection

and in Sicily the Italian government was probably as unpopular as that of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

had been. In efforts to balance the books taxes were raised on salt and tobacco and more tellingly,

as far as the poor were concerned, the tax on milling grain, the

Macinato, which had been introduced into Piedmont by Quintino Sella in 1869 was now

applied to the entire realm. Taxes were levied on mules, the omnipresent beast of burden of the peasantry, whilst

horses and cows usually owned by landowners were not similarly taxed. There were many instances of serious

rioting entered into against the economic policies

being followed by the Italian royal administration. In cases

the battle-cry of the economically distressed rioters was "long live the Pope and Austria". The birth

of the Kingdom of Italy

was not proving to be a straightforward affair. Newly united Italy experienced a wave of mass emigration as

distressed poor people sought new and better lives in the United States and elsewhere.

It was not just the discontented poor of the south that threatened the stability of the

regime. Many adherents of Mazzini and Garibaldi felt betrayed by the state that had

emerged. Austria might still hope to restore her position in Italy. And the Church, still

headed by Pius IX, condemned the new state and all that it stood for.

In these conditions the state had to struggle to survive.

In many areas the masses spoke Latin dialects other than Italian: the former "Tuscan" Latin dialect that had become accepted

as a literary language since the middle ages due to the impressive creativity of Dante and others.

When Italy unified in the 1860s the question of languages other than Italian was never much considered (several

regional dialects continue to survive as 'household' languages) and the

administrative model chosen was designed to annex a dispersed and disconnected plethora of pretty states to

Piedmont.

The national state that emerged was centralized but weak -- precisely what might have been expected - other

things being equal - to give

rise to waves of peripheral resentments and mobilizations.

Liberal doctrine also demanded that the laws and practices be standardized throughout the

land. Piedmontese officials, bringing with them new laws and practices that inadvertently

undermined the economy of the south. In the event the several states

that now newly came under the sovereignty of the House of Savoy in the Kingdom of Italy

did so under the existing Piedmontese constitution, under existing Piedmontese laws and existing Piedmontese

foreign policy arrangements. King Victor Emmanuel II remained as King Victor Emmanuel II even though "Italy"

had never had a King Victor Emmanuel previously. There were cases of resentment, in the south particularly,

of the way Piedmontese organisers were deployed in rearranging aspects of the functioning of the

territories newly under the House of Savoy.

Mazzini, who had remained committed to his republicanism, died at Pisa on 10 March 1872. At this time he was

illegally present, and living under an assumed name, on Italian soil, and was regarded as an outlaw for attempting

insurrection against the king.

Cardinal Secretary of State Antonelli informed Odo Russell, a quasi official British

representative in Rome, that his demise might allow the relaxation of some of the restraints that Cavour had placed

on Italian Republicanism.

Since these times Italians

have sometimes tended to characterise Cavour as being the "brain" of Italian Unification - (with Garibaldi being

sometimes characterised as its "sword" and Mazzini as its "spirit").

The Roman Question

This " Roman Question " where both "Italy" and the Papacy required sovereignty in Rome was resolved some sixty years later through the Lateran Agreements of 1929.Through these agreements the Papacy was to be regarded as sovereign over a 40 hectare (108 acre) Vatican City State. The Papacy in return recognised the existence and sovereignty of an Italian Kingdom that maintained Rome as its capital city.

Several commentators then and later have made the point that the ministers of the government who entered into these Lateran agreements on behalf of Mussolini's Italy were probably less sincerely religious than the ministers of the Italian Kingdom that had seized control of Rome in 1870.

This Cavour, Garibaldi, and Italian Unification page receives many visitors!!!