Solomon Asch experiment (1958)

A study of conformity

Imagine yourself in the following situation: You sign up for a psychology experiment, and on a specified date you and seven others whom you think are also subjects arrive and are seated at a table in a small room. You don't know it at the time, but the others are actually associates of the experimenter, and their behavior has been carefully scripted. You're the only real subject.

The experimenter arrives and tells you that the study in which you are about to participate concerns people's visual judgments. She places two cards before you. The card on the left contains one vertical line. The card on the right displays three lines of varying length.

The experimenter asks all of you, one at a time, to choose which of the three lines on the right card matches the length of the line on the left card. The task is repeated several times with different cards. On some occasions the other "subjects" unanimously choose the wrong line. It is clear to you that they are wrong, but they have all given the same answer.

What would you do? Would you go along with the majority opinion, or would you "stick to your guns" and trust your own eyes?

In 1951 social psychologist Solomon Asch devised this experiment to examine the extent to which pressure from other people could affect one's perceptions. In total, about one third of the subjects who were placed in this situation went along with the clearly erroneous majority.

Asch showed bars like those in the Figure to college students in groups of 8 to 10. He told them he was studying visual perception and that their task was to decide which of the bars on the right was the same length as the one on the left. As you can see, the task is simple, and the correct answer is obvious. Asch asked the students to give their answers aloud. He repeated the procedure with 18 sets of bars. Only one student in each group was a real subject. All the others were confederates who had been instructed to give two correct answers and then to some incorrect answers on the remaining 'staged' trials. Asch arranged for the real subject to be the next-to-the-last person in each group to announce his answer so that he would hear most of the confederates incorrect responses before giving his own. Would he go along with the crowd?

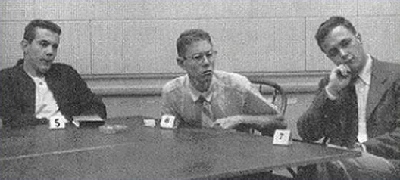

In the above image Solomon Asch is pictured far right, - and the real subject, - third from the right.

To Asch's surprise, 37 of the 50 subjects conformed themselves to the 'obviously erroneous' answers given by the other group members at least once, and 14 of them conformed on more than 6 of the 'staged' trials. When faced with a unanimous wrong answer by the other group members, the mean subject conformed on 4 of the 'staged' trials.

Asch was disturbed by these results: "The tendency to conformity in our society is so strong that reasonably intelligent and well-meaning young people are willing to call white black. This is a matter of concern. It raises questions about our ways of education and about the values that guide our conduct.

This particular "seemingly conflicted and perplexed" individual insisted that "he has to call them as he sees them" and disagreed with the consensus over each of the 'staged' trials.

Why did most subjects conform so readily? When they were interviewed after the experiment, most of them said that they did not really believe their conforming answers, but had gone along with the group for fear of being ridiculed or thought "peculiar." A few of them said that they really did believe the group's answers were correct.

Asch conducted a revised version of his experiment to find out whether the subjects truly did not believe their incorrect answers. When they were permitted to write down their answers after hearing the answers of others, their level of conformity declined to about one third what it had been in the original experiment.

Apparently, people conform for two main reasons: because they want to be liked by the group and because they believe the group is better informed than they are. Suppose you go to a fancy dinner party and notice to your dismay that there are four forks beside your plate. When the first course arrives, you are not sure which fork to use. If you are like most people, you look around and use the fork everyone else is using. You do this because you want to be accepted by the group and because you assume the others know more about table etiquette than you do.

Conformity, group size, and cohesiveness

Asch found that one of the situational factors that influence conformity is the size of the opposing majority. In a series of studies he varied the number of confederates who gave incorrect answers from 1 to 15.

The subjects' responses varied with the level of 'majority opinion' they were faced with.

He found that the subjects conformed to a group of 3 or 4 as readily as they did to a larger group.

However, the subjects conformed much less if they had an "ally" In some of his experiments, Asch instructed one of the confederates to give correct answers. In the presence of this nonconformist, the real subjects conformed only one fourth as much as they did in the original experiment. There were several reasons: First, the real subject observed that the majority did not ridicule the dissenter for his answers. Second, the dissenter's answers made the subject more certain that the majority was wrong. Third, the real subject now experienced social pressure from the dissenter as well as from the majority. Many of the real subjects later reported that they wanted to be like their nonconformist partner (the similarity principle again). Apparently, it is difficult to be a minority of one but not so difficult to be part of a minority of two.

Some of the subjects indicated afterward that they assumed the rest of the people were correct and that their own perceptions were wrong. Others knew they were correct but didn't want to be different from the rest of the group. Some even insisted they saw the line lengths as the majority claimed to see them.

Asch concluded that it is difficult to maintain that you see something when no one else does. The group pressure implied by the expressed opinion of other people can lead to modification and distortion effectively making you see almost anything.

Such celebrated "Men of Letters" as Emerson and Shakespeare have accepted that Human Nature is 'Tripartite' and Emerson accepted that there was an investigable association between Human Nature and History.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

RALPH WALDO EMERSON (1803-1882) was, in his time, the leading voice of intellectual culture in the United States. He remains widely influential to this day through his essays, lectures, poems, and philosophical writings.

In the later eighteen-twenties Ralph Waldo Emerson read, and was very significantly influenced by, a work by a French philosopher named Victor Cousin.

A key section of Cousin's work reads as follows:

"What is the business of history? What is the stuff of which it is made? Who is the personage of history? Man : evidently man and human nature.

There are many different elements in history. What are they? Evidently again, the elements of human nature. History is therefore the development of humanity,

and of humanity only; for nothing else but humanity develops itself, for nothing else than humanity is free. …

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

Even before he had first read Cousin, (in 1829), Emerson had expressed views in his private Journals which suggest that he accepted that Human Nature, and Human Beings, tend to display three identifiable aspects and orientations:

Imagine hope to be removed from the human breast & see how Society will sink, how the strong bands of order & improvement will be relaxed & what a deathlike stillness would take the place of the restless energies that now move the world. The scholar will extinguish his midnight lamp, the merchant will furl his white sails & bid them seek the deep no more. The anxious patriot who stood out for his country to the last & devised in the last beleagured citadel, profound schemes for its deliverance and aggrandizement, will sheathe his sword and blot his fame. Remove hope, & the world becomes a blank and rottenness.

(Journal entry made between October and December, 1823)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

The quotes from Emerson are reminiscent of a line from another "leading voice of intellectual culture" - William Shakespeare.

There's neither honesty, manhood, nor good fellowship in thee.

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

"The first glance at History convinces us that the actions of men proceed from their needs, their passions, their characters and talents; and impresses us with the belief that such needs, passions and interests are the sole spring of actions."

Georg Hegel, 1770-1831, German philosopher, The Philosophy of History (1837)

It is widely known that Plato, pupil of and close friend to Socrates, accepted that Human Beings have a " Tripartite Soul " where individual Human Psychology is composed of three aspects - Wisdom-Rationality, Spirited-Will and Appetite-Desire.