The Milgram Obedience Experiment ~

"repeated" on reality television

Jusqu'ou va la tele, Le Jeu de mort

or - in EnglishHow far will television go? The Game of Death

This show, as broadcast, was presented as a documentary about the negative effects of reality TV worldwide.

It featured a significant French TV generated component which, its naive participants and the studio audience were led to believe, was to be the recording of a pilot programme for a so-called - "La Zone Xtrême", or "The Xtreme Zone" - TV series.

First aired, on 17th March 2010, this documentary effectively featured a re-enactment of the Milgram Obedience Experiment where volunteers who had responded to a newspaper advertisement seeking assistance in a "Study of Memory" had, whist working under the supervision of an "authority figure" who was allegedly researching into Memory, subsequently subjected another person who they believed to be a volunteer just like themselves to extreme electric shocks as punishments when that other persons memory had proved deficient in word association tests.

The "Game of Death" segment as recorded for France 2, (a French public television channel), was intended by its main organiser, Christophe Nick, to be a reality TV recreation of the Milgram Obedience Experiment.

The naive participants had each signed contracts agreeing to inflict electric shocks, if required, on other persons who were to be involved in the process of creating this trial run, were advised that they could not expect to 'win' anything but were to receive a standard €40 fee (held to be equivalent to the $4.00 that Stanley Milgram gave to volunteers in his famous Obedience Experiments in 1963) for their co-operation.

The contestants knew they would gain nothing beyond this. They were nevertheless typically just happy and eager to participate in the development of a pilot game show.

Nick says he got the idea for the project after stumbling across an episode of the French version of The Weakest Link. The willingness of the adult contestants to allow the hostess to belittle them - and their own eagerness to backstab fellow participants for their own gain - convinced him that Milgram's findings about the human submission to authority figures were particularly applicable to reality television.

In his own Study of Obedience Milgram had selected 40 male volunteers who had responded to an advert for persons willing to participate in a Study of Memory.

The 40 who were chosen varied in age, educational attainment, and occupation.

In the Game of Death replication the eighty volunteers were selected, with the advice a company specialized in marketing surveys, to somewhat mirror Milgram's original set of volunteers in terms of age, educational attainment, and occupation - but females as well as males were selected to participate.

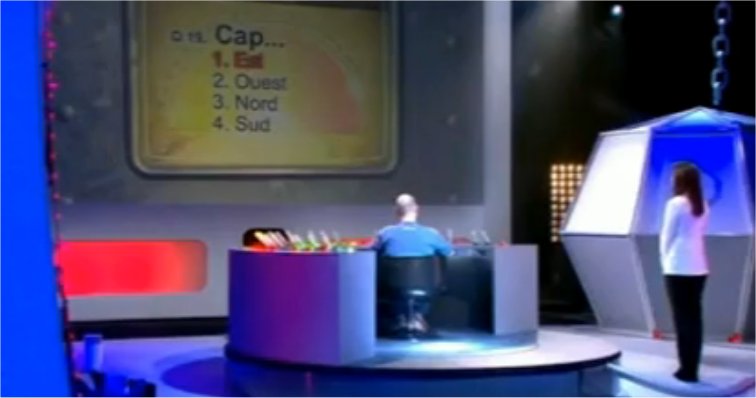

In the ensuing TV studio setting it appeared that a male participant, was assigned a role of being a respondent and was strapped, (and even padlocked!), into a chair by a glamourous assistant under the overall supervision of a well-known and respected TV presenter who was familiar to many because of numerous appearances on the France 2 TV channel.

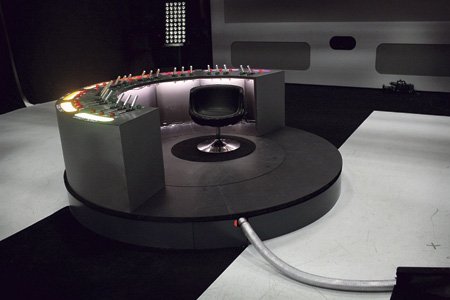

This booth is shown to the right of the platform in the center of the picture of the studio layout below.

Note the evidently "heavy" cabling joining the respondent's booth to the platform where a display of controls is evident on a console.

The heavy cable "obviously" led to the booth where the questioners and the studio audience had seen the respondent strapped and padlocked into a chair.

Another participant was assigned a role as a questioner and was told that he or she would be called upon to test the person confined in the booth with word association tests and whenever the respondent gave an incorrect answer an electric shock was to be administered as punishment.

In the How far will television go? The Game of Death documentary as actually broadcast viewers could see the respondent freeing himself and even leaving the booth by a secret exit BUT in the estimation of the questioner and of the studio audience during the recording he was actually still padlocked into his chair in the booth.

In the series of word association tests, the respondent, identified as "Jean-Paul," was reminded that any wrong answers would merit punishment in the form of electric shocks and was subsequently asked questions by the other participant who had been assigned the role of questioner.

Jean-Paul, (who was actually an actor) was represented during the recordings as remaining out of sight of the questioners but as communicating his pain progressively: first through whimpers, then pleas to stop the electrocutions. These whimpers and pleas were actually pre-recorded and were replayed to the questioners and the studio audience such as to seem to vary in line with the varying levels of electric shocks which were administered by participants in the game show as encouraged and "authorised" by the TV presenter.

As the recordings continued the well known and respected TV presenter was often involved in adding her own endorsement to the infliction of electric shocks for wrong answers despite evident discomfort being voiced by a pre-recorded Jean-Paul.

The studio audience were also involved in requesting "punishments" to be imposed on Jean-Paul where he gave wrong answers.

With no financial incentive on the table the 80 participants who had been individually assigned the role of questioner were typically put through a sequence where they would impose, (against this background of studio audience and TV presenter endorsement), a range of electric shocks.

Participant applying electric shocks

Electric shocks were believed to be delivered on an increasing scale if Jean-Paul continued to give wrong answers. The following image shows a "questioner" imposing a shock in the "choc fort" or "strong shock" range which had been preceded by several levels of chocs légers or light shock, and chocs modérés or moderate shock.

Further electric shocks moved through increasingly severe sounding shock ranges, eventually into a choc dangereux or dangerous shock range - and beyond to XXX!

The procedure followed that of the Milgram Obedience Experiment, the task is the same type (recognition of a word from four), with 'punishments' for incorrect answering being applicable through the simulator of electric shocks from 20 to 460 volts the levers being grouped together and successively labelled:-

| Milgram Experiment (electric shocks ranges) | Le Jeu de mort (chocs électriques) | Electric Shocks simulated on the French TV show |

| Slight Shock | chocs légers | 20, 40, 60 volts |

| Moderate Shock | chocs modérés | 80, 100, 120 volts |

| Strong Shock | chocs forts | 140, 160, 180 volts |

| Very Strong Shock | chocs très forts | 200, 220, 240 volts |

| Intense Shock | chocs intenses | 260, 280, 300 volts |

| Extreme Intensity Shock | chocs très intenses | 320, 340, 360 volts |

| Danger: Severe Shock | chocs dangereux | 380, 400, 420 volts |

| and finally - XXX | et, enfin - XXX | 440, 460 volts |

Several times the pre-recorded voice of Jean-Paul, as replayed in the context of having "apparently received" received electric shocks as punishments, demanded that he should be allowed to stop and insisted that he be allowed to leave - nevertheless the procedure typically continued with increasing electric shocks being inflicted by questioners who were often themselves increasingly distressed at the show presenter and studio audience urging that they carry out the 'punishments' for incorrect answering.

At 320 volts the pre-recorded Jean-Paul explicitly refused to give an answer - he also seemed to maintain a silence after 380 volts - nevertheless in most cases the often conflicted and reluctant questioners continued to ask questions and to administer punishments for incorrect answers.

As electric shocks were apparently applied the shock level was flashed up on screen.

For dramatic purposes Jean-Paul is seen by viewers of the documentary, although known by them to be released the booth, as actually receiving shocks.

The questioners and the studio audience, who have been given reason to believe that Jean-Paul is still padlocked in a chair located in that booth, only hear his "pre-recorded" protests and screams as he apparently "receives" increasingly severe shocks.

The electric shocks console viewed from above.

Not knowing that the screaming Jean-Paul is really an actor, the apparently reluctant questioners, who believed the Xtreme Zone game show was real, typically yielded to the encouragements of the presenter and chants of "Punishment!" from a studio audience who also believed the game was real - punishing Jean-Paul with up to 460 volts of electricity when he got answers wrong - even beyond the point where his cries of "Let me go!" and "I refuse to respond" had fallen silent and he appeared to have passed out or even, perhaps, died.

The severity of the electric shocks being "apparently" delivered was obvious to the questioners being shown as a metered display on the control screen between questions.

Most questioners showed signs of their hating making Jean-Paul suffer, expressed their desire to stop the game, but, apart from 16 participants, they never managed to resist authority.

The 16 questioners who walked out - at some stage or other - were actually a fraction of the overall 80 persons who participated as questioners. This meant 64 persons continued to deliver shocks under the authority of the "somewhat prestigious?" reality TV show format and the promptings of the well-known presenter and the encouragements of the studio audience.

"People were convinced that they'd never succumb to this - and then they discovered they did it in spite of themselves," the shows originator - Christophe Nick told The Associated Press in an interview.

Picture of Christophe Nick

"We were amazed to find that 81 percent of the participants obeyed" the sadistic orders of the television presenter, said Christophe Nick

"They are not equipped to disobey," he told the wire service Agence France-Presse. "They don't want to do it, they try to convince the authority figure that they should stop, but they don't manage to."

One contestant interviewed afterwards said she went along with the game despite knowing that her own grandparents were Jews who had been tortured by the Nazis.

The woman, named as Sophie, said: "Since I was a little girl, I have always asked myself why they (the Nazis) did it. How could they obey such orders? And there I was, obeying them myself."

Another contestant added: "I was worried. But at the same time, I was afraid to spoil the programme."

To minimize participant trauma and adverse criticism generally it was arranged that as soon as recording sessions ended the volunteers involved were notified that they had in fact participated in an experiment. They were informed that their behaviours were normal, and that the context of the experiment was responsible for those behaviours.

They were allowed to meet an evidently healthy and well "Jean-Paul" during this de-briefing who personally thanked them for their assistance.

The questioners were subsequently asked for their permission to be shown on the eventual TV programme. Only three refused.

Speaking about the eighty volunteers Christophe Nick noted:- "Most of them are thrilled to have participated in an experiment that could be useful for something, and some of them are ready to do it all over again!"

The programme draw clear parallels with the experiment carried out by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram.

His experiment measured the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience.

The study began in July 1961, three months after the start of the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem.

Milgram devised the experiments to answer this question: "Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?"

Show producer Christophe Nick said:

"In Milgram's case, 62% of participants obeyed abject orders; with television it's 81%. Therefore you have to ask yourself a question which is

more than about submission to an authority, but about the power of a system, a global system, which is television."

As Milgram wrote in a 1974 article for Harper's Magazine ("The Perils of Obedience") based on his experiment:

[The] most fundamental lesson of our study: ordinary people, simply doing their jobs, and without any particular hostility on their part, can become agents in a terrible destructive process.

Moreover, even when the destructive effects of their work become patently clear, and they are asked to carry out actions incompatible with fundamental standards of morality,

relatively few people have the resources needed to resist authority.

"When it decides to abuse its power, television can do anything to anybody," said Christophe Nick. "It has an absolutely terrifying power."

Ralph Waldo Emerson

RALPH WALDO EMERSON (1803-1882) was, in his time, the leading voice of intellectual culture in the United States. He remains widely influential to this day through his essays, lectures, poems, and philosophical writings.

In the later eighteen-twenties Ralph Waldo Emerson read, and was very significantly influenced by, a work by a French philosopher named Victor Cousin.

A key section of Cousin's work reads as follows:

"What is the business of history? What is the stuff of which it is made? Who is the personage of history? Man : evidently man and human nature.

There are many different elements in history. What are they? Evidently again, the elements of human nature. History is therefore the development of humanity,

and of humanity only; for nothing else but humanity develops itself, for nothing else than humanity is free. …

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

Even before he had first read Cousin, (in 1829), Emerson had expressed views in his private Journals which suggest that he accepted that Human Nature, and Human Beings, tend to display three identifiable aspects and orientations:

Imagine hope to be removed from the human breast & see how Society will sink, how the strong bands of order & improvement will be relaxed & what a deathlike stillness would take the place of the restless energies that now move the world. The scholar will extinguish his midnight lamp, the merchant will furl his white sails & bid them seek the deep no more. The anxious patriot who stood out for his country to the last & devised in the last beleagured citadel, profound schemes for its deliverance and aggrandizement, will sheathe his sword and blot his fame. Remove hope, & the world becomes a blank and rottenness.

(Journal entry made between October and December, 1823)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

The quotes from Emerson are reminiscent of a line from another "leading voice of intellectual culture" - William Shakespeare.

There's neither honesty, manhood, nor good fellowship in thee.

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

Is Human Being more truly Metaphysical than Physical?

"The first glance at History convinces us that the actions of men proceed from their needs, their passions, their characters and talents; and impresses us with the belief that such needs, passions and interests are the sole spring of actions."

Georg Hegel, 1770-1831, German philosopher, The Philosophy of History (1837)

Plato, Socrates and Shakespeare endorse a Tripartite Soul view of Human Nature. Platos' Republic

Understanding the Past and Present. Why is the World the way it is today?

Understanding the Past and Present. Why is the World the way it is today?