The 'Human Evolutionary Tree'

in the opinion of Science

This graphic shows such a popularly accepted Monkey to Man procession.

The scientific view of the origins of species, which has contributed to the secularisation of the west by inherently posing difficult questions to faith, holds that there were many naturally occuring changes in physique and behaviour - some of these proved beneficial in terms of survival - and were locally reinforced by such "successes-in-survival" allowing several branching divergences, based on these survival-favouring changes, to produce an evolutionary tree of related species - including mankind!

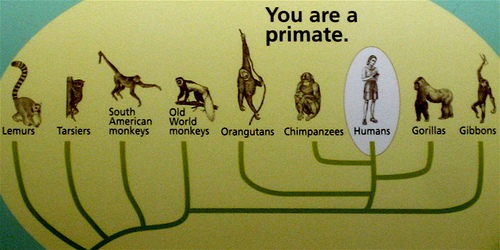

The following graphic, attributable to The National Museum of Natural History - Washington, D.C., demonstrates something of the Darwininian / Scientific approach to visualising the Human Evolutionary Tree.

Science holds that existing primate species can be divided into six subgroups: lemurs, lorises, tarsiers, New World monkeys, Old World monkeys, and apes and humans.

Science further holds that the changes that allowed Humans to feature as part of a primate / human evolutionary tree, and which allowed Humanity to become established as we know it today, were very slowly accumulated due to various "survival advantages" that these changes conferred allowing their possessors to be more generally successful in the struggle for life but particularly so in the gaining of foodstuffs to nourish themselves, their families, and their friends.

The concept of a Human Evolutionary Tree is itself very directly related to more generalised Tree of Life concepts which lie at the heart of Darwinian Evolutionary Theory.

As early as July 1837 Darwin opened a notebook to record his thoughts on "that mystery of mysteries - the origin of species" as this entry from his diary relates:-

In July I opened my first note-book for facts in relation to the Origin of Species, about which I had long reflected, and never

ceased working on it for the next twenty years.

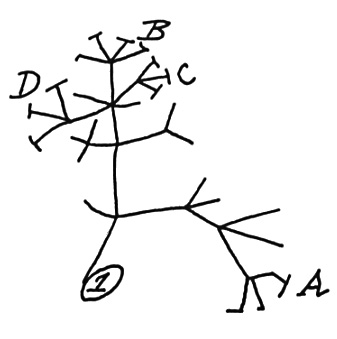

The direction of the development of Darwin's thoughts can perhaps be illustrated by this famous

Tree of Life sketch from his Notebook B dating from 1837-8:-

The direction of the development of Darwin's thoughts can perhaps be illustrated by this famous

Tree of Life sketch from his Notebook B dating from 1837-8:-

Charles Darwin's early evolutionary theory insight of how a branching tree-like genus of related species might originate by divergence from a starting point (1) to effectively establish related species at such notional points as A, B, C and D.

There is an accompanying text annotation, from Darwin's notebook B now stored in Cambridge University library, that reads:-

I think

Case must be that one generation then should be as many living as now. To do this & to have many species in same genus (as is) requires extinction.

Thus between A & B immense gap of relation. C & B the finest gradation, B & D rather greater distinction. Thus genera would be formed. - bearing relation (page 36 ends - page 37 begins) to ancient types with several extinct forms.

Although Charles Darwin seems to have formed his initial evolutionist hunches in or around 1835 his most famous work on the Evolutionary Origin of Species was not published until 1859.

His chapter summary to "Chapter IV. Natural Selection" in this Origin of Species work of 1859 features this - Tree of Life - related assertion:-

The affinities of all the beings of the

same class have sometimes been represented by a great tree. I believe this

simile largely speaks the truth. The green and budding twigs may represent

existing species; and those produced during former years may represent the

long succession of extinct species. At each period of growth all the

growing twigs have tried to branch out on all sides, and to overtop and

kill the surrounding twigs and branches, in the same manner as species and

groups of species have at all times overmastered other species in the

great battle for life. The limbs divided into great branches, and these

into lesser and lesser branches, were themselves once, when the tree was

young, budding twigs; and this connexion of the former and present buds by

ramifying branches may well represent the classification of all extinct

and living species in groups subordinate to groups. Of the many twigs

which flourished when the tree was a mere bush, only two or three, now

grown into great branches, yet survive and bear the other branches; so

with the species which lived during long-past geological periods, very few

have left living and modified descendants.

Thus, from the 'Darwinian Theoretical' perspective, the Human Evolutionary Tree it would propose becomes a branch of a mind-blowingly ancient general Tree of Life.

In his work of 1859, issued as it was into a fairly faith-accepting victorian England, Darwin avoided speculating that Human Beings were themselves subject to evolutionary processes.

Nevertheless, despite much controversy, the view that Humans also 'evolved' gradually gained an increasing acceptance - with consequences for religious belief - as scientifically inclined contemporaries such as Thomas Henry Huxley ventured to explicitly suggest, (in his Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature published in 1863), that Human Beings were themselves a species that was itself closely related to some ape species.

Darwinism and Evolutionary Science in the "westernised" world has now substantially accepted, for well over a century, that Humans have 'evolved' and that there is a Primate / Human evolutionary tree of closely related species.

Artistic spoof on the human evolutionary tree

depicting a modern man on a steel branch.

Is Human Being more truly Metaphysical than Physical?

Ralph Waldo Emerson

RALPH WALDO EMERSON (1803-1882) was, in his time, the leading voice of intellectual culture in the United States. He remains widely influential to this day through his essays, lectures, poems, and philosophical writings.

In the later eighteen-twenties Ralph Waldo Emerson read, and was very significantly influenced by, a work by a French philosopher named Victor Cousin.

A key section of Cousin's work reads as follows:

"What is the business of history? What is the stuff of which it is made? Who is the personage of history? Man : evidently man and human nature.

There are many different elements in history. What are they? Evidently again, the elements of human nature. History is therefore the development of humanity,

and of humanity only; for nothing else but humanity develops itself, for nothing else than humanity is free. …

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

Even before he had first read Cousin, (in 1829), Emerson had expressed views in his private Journals which suggest that he accepted that Human Nature, and Human Beings, tend to display three identifiable aspects and orientations:

Imagine hope to be removed from the human breast & see how Society will sink, how the strong bands of order & improvement will be relaxed & what a deathlike stillness would take the place of the restless energies that now move the world. The scholar will extinguish his midnight lamp, the merchant will furl his white sails & bid them seek the deep no more. The anxious patriot who stood out for his country to the last & devised in the last beleagured citadel, profound schemes for its deliverance and aggrandizement, will sheathe his sword and blot his fame. Remove hope, & the world becomes a blank and rottenness.

(Journal entry made between October and December, 1823)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

The quotes from Emerson are reminiscent of a line from another "leading voice of intellectual culture" - William Shakespeare.

There's neither honesty, manhood, nor good fellowship in thee.

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

Plato, Socrates and Shakespeare endorse a 'Tripartite Soul' view of Human Nature. Platos' Republic