The Allegory of the Cave

with quotes from Book VII of Plato's - The Republic

Amongst the many works attributed to Plato's authorship is his "The Republic" wherein is set out a series of discourses that allegedly took place between Socrates and a number of other persons who variously arrived and departed as the discussions continued.

It is in this record, made by Plato, "of "Socrates? and of his own?", philosophising that most intriguing themes are developed.

The meaning of the Allegory

We can see the meaning of the Allegory of the Cave, as presented in the Book VII of Plato's The Republic, as discussing, or reflecting on, how far people may claim to be enlightened or unenlightened. It may well be that it has religious overtones relating to the Orphic mysticism that was a strong faith background to the works of Socrates and Plato. Many people accept that in the Allegory of the Cave Plato seems to be suggesting that a philosophic realisation is possible and can help to lead people away from an unenlightened, into an enlightened, state.The following video clip, about the Myth or Allegory of the Cave, is much visited on YouTube, and is very highly rated there.

The following quotes come from Book VII of Plato's most famous work - The Republic.

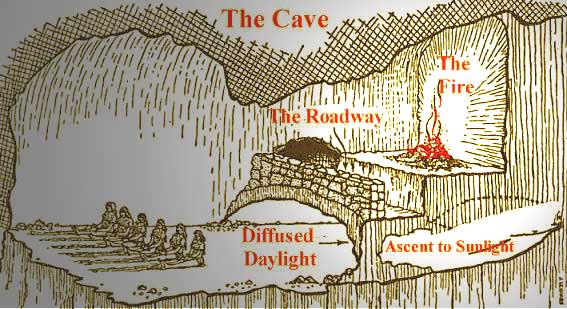

Now then, I proceeded to say, go on to compare our natural

condition, so far as education and ignorance are concerned, to

the state of things like the following. Imagine a number of men

living in an underground chamber, with an entrance open to the

light, extending along the entire length of the chamber, in which

they have been confined, from their childhood, with their legs

and necks so shackled, that they are obliged to sit still and

look straight forwards, because their chains render it impossible

for them to turn their heads round: and imagine a bright fire

burning some way off, above and behind them, and an elevated

roadway passing between the fire and the prisoners, with a low

wall built along it, like the screens which conjurors put up in

front of their audience, and above which they exhibit their

wonders.

I have it, he replied.

Also figure to yourself a number of persons walking behind this wall, and carrying with them statues of men, and images of other animals, wrought in wood and stone and all kinds of materials, together with various other articles, which overtop the wall; and, as you might expect, let some of the passers-by be talking, and others silent.

You are describing a strange scene, and strange prisoners.

They resemble us, I replied. For let me ask you, in the first place, whether persons so confined could have seen anything of themselves or of each other, beyond the shadows thrown by the fire upon the part of the chamber facing them? Certainly not, if you suppose them to have been compelled all their lifetime to keep their heads unmoved.

And is not their knowledge of the things carried past them equally limited?

Unquestionably it is.

And if they were able to converse with one another, do you not think that they would be in the habit of giving names to the objects they saw before them?

Doubtless they would.

Again: if their prison-house returned an echo from the part facing them, whenever one of the passers-by opened his lips, to what, let me ask you, could they refer the voice, if not to the shadow which was passing?

Unquestionably they would refer it to that.

Then surely such persons would hold the shadows of those manufactured articles to be the only realities.

Without a doubt they would.

Now consider what would happen if the course of nature brought them a release from their fetters, and a remedy form their foolishness in the following manner. Let us suppose that one of them has been released, and compelled suddenly to stand up, and turn his neck round and walk with open eyes towards the light; let us suppose that he goes through all these actions with pain, and that the dazzling splendour renders him incapable of discerning those objects of which he formerly used to see the shadows. What answer should you expect him to make, if someone were to tell him that in those days he was watching foolish phantoms, but that now he is somewhat nearer to reality, and is turned toward things more real, and sees more correctly; above all, if he were to point out to him the several objects that are passing by, and question him, and compel him to answer what they are? Should you not expect him to be puzzled, and to regard his old visions as truer than the objects now forced upon his notice?

Yes, much truer.

And if he were further compelled to gaze at the light itself, would not his eyes, think you, be distressed, and would he not shrink and turn away to the things which he could see distinctly, and consider them to be really clearer than the things pointed out to him?

Just so.

And if some one were to drag him violently up the rough and steep ascent from the chamber, and refuse to let him go till he had drawn him out into the light of the sun, would he not, think you, be vexed and indignant at such treatment, and on reaching the light, would he not find his eyes so dazzled by the glare as to be incapable of making out so much as one of the objects that are now called true?

Yes, he would find it so at first.

Hence, I suppose, habit will be necessary to enable him to perceive objects in that upper world. At first he will be most successful in distinguishing shadows; then he will discern the reflections of men and other things in water, and afterwards the realities; after this he will raise his eyes to encounter the light of the moon and stars, finding it less difficult to study the heavenly bodies and the heaven itself by night, than the sun and the sun's light by day.

Doubtless.

Last of all, I imagine, he will be able to observe and contemplate the nature of the sun, not as it appears in water or on alien ground, but as it is in itself in its own territory.

Of course.

His next step will be to draw the conclusion, that the sun is the author of the seasons and the years, and the guardian of all things in the visible world, and in a manner the cause of all those things which he and his companions used to see.

Obviously this will be his next step.

What then? When he recalls to mind his first habitation, and the wisdom of the place, and his old fellow- prisoners, do you not think he will congratulate himself on the change, and pity them?

Assuredly he will.

And if it was their practice in those days to receive honour and commendations one from another, and to give prizes to him who had the keenest eye for a passing object, and who remembered best all that used to precede and follow and accompany it, and from these data divined most ably what was going to come next, do you fancy that he will covet these prizes, and envy those who receive honour and exercise authority among them? Do you not rather imagine that he will rather imagine that he will feel what Homer describes, and wish extremely

"To drudge on the lands of a master,

Under a portionless wight."

and be ready to go through anything, rather than entertain those opinions, and live in that fashion?

For my own part, he replied, I am quite of that opinion. I believe he would consent to go through anything rather than live in that way.

And now consider what would happen if such a man were to descend again and seat himself on his old seat? Coming so suddenly out of the sun, would he not find his eyes blinded with the gloom of the place?

Certainly, he would.

And if he were forced to deliver his opinion again, touching the shadows aforesaid, and to enter the lists against those who had always been prisoners, while his sight continued dim and his eyes unsteady, - and if this process of initiation lasted a considerable time, - would he not be made a laughingstock, and would it not be said of him, that he had gone up only to come back again with his eyesight destroyed, and that it was not worth while even to attempt the ascent? And if anyone endeavoured to set them free and carry them to the light, would they not go so far as to put him to death, if they could only manage to get him into their power?

Yes, that they would.

Now this imaginary case, my dear Glaucon, you must apply in all its parts to our former statements, by comparing the region which the eye reveals, to the prison-house, and the light of the fire therein to the power of the sun: and if, by the upward ascent and the contemplation of the upper world, you understand the mounting of the soul into the intellectual region, you will hit the tendency of my own surmises, since you desire to be told what they are; though, indeed, God only knows whether they are correct. But, be that as it may, the view which I take of the subject is to the following effect. In the world of knowledge, the essential Form of Good is the limit of our inquiries, and can barely be perceived; but, when perceived, we cannot help concluding that it is in every case the source of all that is bright and beautiful,- in the visible world giving birth to light and its master, and in the intellectual world dispensing, immediately and with full authority, truth and reason;- and that whosoever would act wisely, either in private or in public, must set the Form of Good before his eyes.

I have it, he replied.

Also figure to yourself a number of persons walking behind this wall, and carrying with them statues of men, and images of other animals, wrought in wood and stone and all kinds of materials, together with various other articles, which overtop the wall; and, as you might expect, let some of the passers-by be talking, and others silent.

You are describing a strange scene, and strange prisoners.

They resemble us, I replied. For let me ask you, in the first place, whether persons so confined could have seen anything of themselves or of each other, beyond the shadows thrown by the fire upon the part of the chamber facing them? Certainly not, if you suppose them to have been compelled all their lifetime to keep their heads unmoved.

And is not their knowledge of the things carried past them equally limited?

Unquestionably it is.

And if they were able to converse with one another, do you not think that they would be in the habit of giving names to the objects they saw before them?

Doubtless they would.

Again: if their prison-house returned an echo from the part facing them, whenever one of the passers-by opened his lips, to what, let me ask you, could they refer the voice, if not to the shadow which was passing?

Unquestionably they would refer it to that.

Then surely such persons would hold the shadows of those manufactured articles to be the only realities.

Without a doubt they would.

Now consider what would happen if the course of nature brought them a release from their fetters, and a remedy form their foolishness in the following manner. Let us suppose that one of them has been released, and compelled suddenly to stand up, and turn his neck round and walk with open eyes towards the light; let us suppose that he goes through all these actions with pain, and that the dazzling splendour renders him incapable of discerning those objects of which he formerly used to see the shadows. What answer should you expect him to make, if someone were to tell him that in those days he was watching foolish phantoms, but that now he is somewhat nearer to reality, and is turned toward things more real, and sees more correctly; above all, if he were to point out to him the several objects that are passing by, and question him, and compel him to answer what they are? Should you not expect him to be puzzled, and to regard his old visions as truer than the objects now forced upon his notice?

Yes, much truer.

And if he were further compelled to gaze at the light itself, would not his eyes, think you, be distressed, and would he not shrink and turn away to the things which he could see distinctly, and consider them to be really clearer than the things pointed out to him?

Just so.

And if some one were to drag him violently up the rough and steep ascent from the chamber, and refuse to let him go till he had drawn him out into the light of the sun, would he not, think you, be vexed and indignant at such treatment, and on reaching the light, would he not find his eyes so dazzled by the glare as to be incapable of making out so much as one of the objects that are now called true?

Yes, he would find it so at first.

Hence, I suppose, habit will be necessary to enable him to perceive objects in that upper world. At first he will be most successful in distinguishing shadows; then he will discern the reflections of men and other things in water, and afterwards the realities; after this he will raise his eyes to encounter the light of the moon and stars, finding it less difficult to study the heavenly bodies and the heaven itself by night, than the sun and the sun's light by day.

Doubtless.

Last of all, I imagine, he will be able to observe and contemplate the nature of the sun, not as it appears in water or on alien ground, but as it is in itself in its own territory.

Of course.

His next step will be to draw the conclusion, that the sun is the author of the seasons and the years, and the guardian of all things in the visible world, and in a manner the cause of all those things which he and his companions used to see.

Obviously this will be his next step.

What then? When he recalls to mind his first habitation, and the wisdom of the place, and his old fellow- prisoners, do you not think he will congratulate himself on the change, and pity them?

Assuredly he will.

And if it was their practice in those days to receive honour and commendations one from another, and to give prizes to him who had the keenest eye for a passing object, and who remembered best all that used to precede and follow and accompany it, and from these data divined most ably what was going to come next, do you fancy that he will covet these prizes, and envy those who receive honour and exercise authority among them? Do you not rather imagine that he will rather imagine that he will feel what Homer describes, and wish extremely

"To drudge on the lands of a master,

Under a portionless wight."

and be ready to go through anything, rather than entertain those opinions, and live in that fashion?

For my own part, he replied, I am quite of that opinion. I believe he would consent to go through anything rather than live in that way.

And now consider what would happen if such a man were to descend again and seat himself on his old seat? Coming so suddenly out of the sun, would he not find his eyes blinded with the gloom of the place?

Certainly, he would.

And if he were forced to deliver his opinion again, touching the shadows aforesaid, and to enter the lists against those who had always been prisoners, while his sight continued dim and his eyes unsteady, - and if this process of initiation lasted a considerable time, - would he not be made a laughingstock, and would it not be said of him, that he had gone up only to come back again with his eyesight destroyed, and that it was not worth while even to attempt the ascent? And if anyone endeavoured to set them free and carry them to the light, would they not go so far as to put him to death, if they could only manage to get him into their power?

Yes, that they would.

Now this imaginary case, my dear Glaucon, you must apply in all its parts to our former statements, by comparing the region which the eye reveals, to the prison-house, and the light of the fire therein to the power of the sun: and if, by the upward ascent and the contemplation of the upper world, you understand the mounting of the soul into the intellectual region, you will hit the tendency of my own surmises, since you desire to be told what they are; though, indeed, God only knows whether they are correct. But, be that as it may, the view which I take of the subject is to the following effect. In the world of knowledge, the essential Form of Good is the limit of our inquiries, and can barely be perceived; but, when perceived, we cannot help concluding that it is in every case the source of all that is bright and beautiful,- in the visible world giving birth to light and its master, and in the intellectual world dispensing, immediately and with full authority, truth and reason;- and that whosoever would act wisely, either in private or in public, must set the Form of Good before his eyes.

A further aid to an appreciation of

the meaning of the Allegory of the Cave

Later in this same Book VII of The Republic Plato

introduces the notion that there are four planes upon which

people know about things. These planes are words, perception,

concepts, and ideas. These planes may be compared to the various

levels depicted in the allegory of the Cave.

Men start out in the realm of words - where shadows are thrown upon the wall. A more true reality is that of the road and the images being carried by the persons passing along it. These are as perceptions which cast the immediately apparent reality of shadows (words) upon the wall. The next approach to a fuller realisation of reality is more testing - it involves being out in the glare of the Sun and the conceptual recognition that the images being carried are not as real as the variously motivated people carrying them. The next phase suggested is that of ideas where people become, philosophic, observers of the world.

Other meaningful and reflective quotes

from Plato's - The Republic

Two other major quotes from Plato's The Republic are featured on this page as they can be seen

as inherently reflecting, very directly, on Plato's own observations on the World!!!

...can we possibly refuse to admit that there exist in each of us the same generic parts and characteristics as are found in the state? For I presume the state has not received them from any other source. It would be ridiculous to imagine that the presence of the spirited element in cities is not to be traced to individuals, wherever this character is imputed to the people, as it is to the natives of Thrace, and Scythia, and generally speaking, of the northern countries; or the love of knowledge, which would be chiefly attributed to our own country; or the love of riches, which people would especially connect with the Phoenicians and the Egyptians.

Certainly.

This then is a fact so far, and one which it is not difficult to apprehend.

No, it is not.

But here begins a difficulty. Are all our actions alike performed by the one predominant faculty, or are there three faculties operating severally in our different actions? Do we learn with one internal faculty, and become angry with another, and with a third feel desire for all the pleasures connected with eating and drinking, and the propagation of the species; or upon every impulse to action, do we perform these several actions with the whole soul…

Socrates à la Plato's Republic Book IV

...As there are three parts, so there appear to me to be three pleasures, one appropriate to each part; and similarly three appetites, and governing principles.

Explain yourself.

According to us, one part was the organ whereby a man learns, and another that whereby he shews spirit. The third was so multiform that we were unable to address it by a single appropriate name; so we named it after that which is its most important and strongest characteristic. We called it appetitive, on account of the violence of the appetites of hunger, thirst, and sex, and all their accompaniments; and we called it peculiarly money-loving, because money is the chief agent in the gratification of such appetites.

Yes, we were right.

Then if we were to assert that the pleasure and the affection of this third part have gain for their object, would not this be the best summary of the facts upon which we should be likely to settle by force of argument, as a means of conveying a clear idea to our own minds, whenever we spoke of this part of the soul? And shall we not be right in calling it money-loving and gain-loving?

I confess I think so, he replied.

Again, do we not maintain that the spirited part is wholly bent on winning power and victory and celebrity?

Certainly we do.

Then would the title of strife-loving and honour-loving be appropriate to it?

Yes, most appropriate?

Well, but with regard to the part by which we learn, it is obvious to everyone that its entire and constant aim is to know how the truth stands, and that this of all the elements of our nature feels the least concern for wealth and reputation.

Yes, quite the least.

Then shall we not do well to call it knowledge-loving and wisdom-loving?

Of course we shall.

Does not this last reign in the souls of some persons, while in the souls of other people one or other of the two former, according to circumstances is dominant?

You are right.

And for these reasons may we assert that men may be primarily classed as lovers of wisdom, of strife, and of gain?

Yes, certainly.

And that there are three kinds of pleasure, respectively underlying the three classes?

Exactly so.

Now are you aware, I continued, that if you choose to ask three such men each in his turn, which of these lives is pleasantest, each will extol his own beyond the others? Thus the money-making man will tell you, that compared with the pleasures of gain, the pleasures of being honoured or of acquiring knowledge are worthless, except in so far as they can produce money.

True.

But what of the honour-loving man? Does he not look upon the pleasure derived from money as a vulgar one, while, on the other hand, he regards the pleasure derived from learning as a mere vapour and absurdity unless honour be the fruit of it.

That is precisely the case.

And must we not suppose that the lover of wisdom regards all other pleasures as, by comparison, very far inferior to the pleasure of knowing how the truth stands, and of being constantly occupied with this pursuit of knowledge…

Socrates à la Plato's Republic Book VIII

"Idealism" in Western Philosophy

Wikipedia's definition of Idealism begins:- In philosophy, idealism is the group of philosophies which assert that reality, or reality as we can know it, is fundamentally mental, mentally constructed, or otherwise immaterial.

Plato is generally considered to be the most important figure in the history of Western Philosophy.

It has been suggested that philosophy, in the West since his time, can be characterised as having been "A Series of Footnotes to Plato".

An attempt at constructing some further such footnotes now follows and will bring in testimony from:-

- Immanuel Kant

- the most influential western philosopher of recent centuries.

- Victor Cousin

- a celbrated French philosopher.

and - - Ralph Waldo Emerson

- who was much influenced by Plato and by Kant and who saw himself

as belonging to the same "Idealist" philosophical tradition as Plato and Kant.

Plato asks us some leading questions in Book IV of his most famous work, The Republic, including:-

…can we possibly refuse to admit that there exist in each

of us the same generic parts and characteristics as are found in

the state?

and

Are all our actions alike

performed by the one predominant faculty, or are there three

faculties operating severally in our different actions? Do we

learn with one internal faculty, and become angry with another,

and with a third feel desire for all the pleasures connected with

eating and drinking, and the propagation of the species; or upon

every impulse to action, do we perform these several actions with

the whole soul…

Human Being seems

to be rather "Tripartite"

The following view suggests that, (non-doctrinaire), Societies themselves!!! often have something of a "Tripartite" character:-

Immanuel Kant may be held to broadly supportive of such far-reaching "Idealism"

"Whatever concept one may hold, from a metaphysical point of view, concerning the freedom of the will, certainly its appearances, which are human actions,

like every other natural event, are determined by universal laws. However obscure their causes, history, which is concerned with narrating these appearances,

permits us to hope that if we attend to the play of freedom of the human will in the large, we may be able to discern a regular movement in it, and that what

seems complex and chaotic in the single individual may be seen from the standpoint of the human race as a whole to be a steady and progressive though

slow evolution of its original endowment."

Immanuel Kant

Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View (1784)

Immanuel Kant

Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View (1784)

Victor Cousin may be held to broadly accepting of such far-reaching "Idealism"

What is the business of history? What is the

stuff of which it is made? Who is the personage

of history? Man : evidently man and human

nature. There are many different elements in history. What are they?

Evidently again, the elements of human nature. History is therefore the

development of humanity, and of humanity only;

for nothing else but humanity developes itself, for

nothing else than humanity is free. ...

... Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations.

Victor Cousin

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1832)

... Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations.

Victor Cousin

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1832)

Ralph Waldo Emerson seems to be rather convinced of the validity of this, undeniably, far-reaching "Idealism"

In his essay "History" Ralph Waldo Emerson sets out an approach to History where the "innate Humanity" that is common to all of mankind is seen as operating throughout the ages in the shaping of events.

"There is one mind common to all individual men.

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. All the facts of history pre-exist as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of this manifold spirit to the manifold world".

Later in the same essay we find this:-

"In old Rome the public roads beginning at the Forum proceeded north, south, east, west, to the centre of every province of the empire, making each market-town of Persia, Spain, and Britain pervious to the soldiers of the capital: so out of the human heart go, as it were, highways to the heart of every object in nature, to reduce it under the dominion of man. A man is a bundle of relations, a knot of roots, whose flower and fruitage is the world. His faculties refer to natures out of him, and predict the world he is to inhabit, as the fins of the fish foreshow that water exists, or the wings of an eagle in the egg presuppose air. He cannot live without a world."

The above quotes are drawn from Emerson's ~ History, (an essay of 1841).

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. All the facts of history pre-exist as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of this manifold spirit to the manifold world".

Later in the same essay we find this:-

"In old Rome the public roads beginning at the Forum proceeded north, south, east, west, to the centre of every province of the empire, making each market-town of Persia, Spain, and Britain pervious to the soldiers of the capital: so out of the human heart go, as it were, highways to the heart of every object in nature, to reduce it under the dominion of man. A man is a bundle of relations, a knot of roots, whose flower and fruitage is the world. His faculties refer to natures out of him, and predict the world he is to inhabit, as the fins of the fish foreshow that water exists, or the wings of an eagle in the egg presuppose air. He cannot live without a world."