Alfred Russel Wallace biography

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) was born in Usk, Monmouthshire (now part of Gwent), Wales.

After leaving school in 1837 at the age of fourteen, due to his family's financial constraints, he became passionately interested in beetle collecting and other aspects of natural history.

It was in 1844 that a semi-scientific work entitled "Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation" was first published, by an author who chose to remain anonymous.

This work caused quite a sensation, received a wide readership, and became a best-seller. It brought together various ideas of stellar evolution with the progressive transmutation of species governed by God-given laws in an accessible narrative which seemed to offer to tie together numerous scientific theories of the age.

Included in its content was a suggestion that, at the time of Creation, create-ures were invested with the potential for progressive development.

On December 28th 1845 Alfred Russel Wallace wrote to his friend Henry Walter Bates (1842-52) concerning this work that both had recently read:-

I have rather a more favourable

opinion of the "Vestiges" than

you appear to have -

I do not consider it as a hasty generalisation, but rather as an ingenious hypothesis strongly supported by some striking facts and analogies but which remains to be proved by more facts & the additional light which future researchers may throw upon the subject - it at all events furnishes a subject for every observer of nature to turn his attention to; every fact he observes must make either for or against it, and it thus furnishes both an incitement to the collection of facts & an object to which to apply them when collected -

I would observe that many eminent writers gave great support to the theory of the progressive development of species in Animals & plants -

It seems that from around this time Wallace consciously accepted the possibility that species could transmutate.

I do not consider it as a hasty generalisation, but rather as an ingenious hypothesis strongly supported by some striking facts and analogies but which remains to be proved by more facts & the additional light which future researchers may throw upon the subject - it at all events furnishes a subject for every observer of nature to turn his attention to; every fact he observes must make either for or against it, and it thus furnishes both an incitement to the collection of facts & an object to which to apply them when collected -

I would observe that many eminent writers gave great support to the theory of the progressive development of species in Animals & plants -

A letter of 1847 by Wallace to Bates includes this passage:-

(The family referred to being a zoological one)

"I begin to feel rather dissatisfied with a mere local collection; little is to be learnt by it. I should like to take some one family to study thoroughly, principally with a view to the theory of the

origin of species. By that means I am strongly of opinion that some definite results might be arrived at."

Late in life Alfred Russel Wallace wrote an autobiographical work. In relation to this particular letter he wrote:-

And at the very end of the letter I say: "There is a work published by the Ray Society I should much like to see, Okens Elements of Physiophilosophy. There is a review of it in the Athenæum. It contains some remarkable views on my favourite subject - the variations, arrangements, distribution, etc., of species."

These extracts from my early letters to Bates suffice to show that the great problem of the origin of species was already distinctly formulated in my mind; that I was not satisfied with the more or less vague solutions at that time offered; that I believed the conception of evolution through natural law so clearly formulated in the "Vestiges" to be, so far as it went, a true one; and that I firmly believed that a full and careful study of the facts of nature would ultimately lead to a solution of the mystery.

Alfred Russel Wallace : My Life, pp. 257.

By 1847 Wallace had encouraged his friend Bates to join him in a Natural History related project. Insights were to be very possibly to be gained in foreign

regions. The project could be funded initially from their personal savings, from sales of beetle specimens from their collections to other enthusiasts, and subsequently by gentlemen naturalists or scientific institutions back home who would pay well for interesting samples of flora and fauna collected in remote locations.

These extracts from my early letters to Bates suffice to show that the great problem of the origin of species was already distinctly formulated in my mind; that I was not satisfied with the more or less vague solutions at that time offered; that I believed the conception of evolution through natural law so clearly formulated in the "Vestiges" to be, so far as it went, a true one; and that I firmly believed that a full and careful study of the facts of nature would ultimately lead to a solution of the mystery.

Alfred Russel Wallace : My Life, pp. 257.

In 1848 he travelled to the Amazon basin in association with Bates and they spent several years there, jointly or seperately, collecting plant and animal specimens. Wallace himself similarly employed the Malay Archipelago and the Spice Islands(1854-62).

In September 1855 a paper entitled On the Law which has regulated the Introduction of New Species by ALFRED R. WALLACE, F.R.G.S. (i.e. Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society) appeared in a well-regarded scientifically inclined publication known as the Annals and Magazine of Natural History.

In this paper Wallace set out his " Sarawak Law " which he claimed to have discovered some ten years previously and which he had since then been subject to testing. This possible Law being that:-

Every species has come into existence coincident both in space and time with a pre-existing closely allied species.

Shortly thereafter Wallace's paper continues:-

the order in which the several species came into existence, each one having had for its immediate antitype a closely related species existing at the time of its origin. It is evidently possible that two or three distinct species may have had a common antitype, and that each of these may again have become the antitypes from which other closely allied species were created.

This paper was read by Sir Charles Lyell who found its contents to suggest strongly that

Species were not fixed creations of God, but were in fact naturally mutable. As a friend of Charles Darwin,

who knew that Darwin had been

considering the Emergence of Species for a considerable time, he consequently urged Darwin to

make efforts to complete his work on related subjects to establish academic priority for his own ideas.

Darwin did read Wallace's paper but later commented about Wallace's work - "it seems all creation with him."

Wallace theorised on the basis of his findings and was influenced in this theorising by Thomas Malthus' Essay on Population. The outcome of Wallace's ruminations was that he went on to propound a theory of the evolutionary origin of species by natural selection.

It was while waiting at Ternate in order to get ready for my next journey, and to decide where I should go, that the idea already referred to

occurred to me. It has been shown how, for the preceding eight or nine years, the great problem of the origin of the species had been continually

pondered over, and how my varied observations and study had been made use of to lay the foundation for its full discussion and elucidation.

My paper written at Sarawak rendered it certain to my mind that the change had taken place by natural succession and descent - one species

becoming changed either slowly or rapidly into another. But the exact process of the change and the causes which led to it were absolutely

unknown and appeared almost inconceivable. The great difficulty was to understand how, if one species was gradually changed into another,

there continued to be so many quite distinct species, so many which differed from their nearest allies by slight yet perfectly definite and

constant characters. One would expect that if it was a law of nature that species were continually changing so as to become in time new and

distinct species, the world would be full of an inextricable mixture of various slightly different forms, so that the well-defined and constant

species we see would not exist. Again, not only are species, as a rule, separated from each other by distinct external characters, but they

almost always differ also to some degree in their food, in the places they frequent, in their habits and instincts, all these characters are

quite as definite and constant as are the external characters. The problem then was, not only how and why do species change, but how and why

do they change into new and well-defined species, distinguished from each other in so many ways; why and how do they become so exactly adapted

to distinct modes of life; and why do all the intermediate grades die out (as geology shows they have died out) and leave only clearly defined and well-marked species, genera, and higher groups of animals.

Now, the new idea or principle which Darwin had arrived at twenty years before, and which occurred to me at this time, answers all these questions and solves all these difficulties, and it is because it does so, and also because it is in itself self-evident and absolutely certain, that it has been accepted by the whole scientific world as affording a true solution of the great problem of the origin of the species.

At the time in question I was suffering from a sharp attack of intermittent fever, and every day during the cold and succeeding hot fits had to lie down for several hours, during which time I had nothing to do but to think over any subjects then particularly interesting me. One day something brought to my recollection Malthus's "Principles of Population", which I had read about twelve years before. I thought of his clear exposition of "the positive checks to increase" - disease, accidents, war, and famine - which keep down the population of savage races to so much lower an average than that of more civilized peoples. It then occurred to me that these causes or their equivalents are continually acting in the case of animals also; and as animals usually breed much more rapidly than does mankind, the destruction every year from these causes must be enormous in order to keep down the numbers of each species, since they evidently do not increase regularly from year to year, as otherwise the world would long ago have been densely crowded with those that breed most quickly. Vaguely thinking over the enormous and constant destruction which this implied, it occurred to me to ask the question, Why do some die and some live? And the answer was clearly, that on the whole the best fitted live. From the effects of disease the most healthy escaped; from enemies, the strongest, the swiftest, or the most cunning; from famine, the best hunters or those with the best digestion; and so on. Then it suddenly flashed upon me that this self-acting process would necessarily improve the race, because in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain - that is, the fittest would survive. Then at once I seemed to see the whole effect of this, that when changes of land and sea, or of climate, or of food-supply, or of enemies occurred - and we know that such changes have always been taking place - and considering the amount of individual variation that my experience as a collector had shown me to exist, then it followed that all the changes necessary for the adaptation of the species to the changing conditions would be brought about; and as great changes in the environment are always slow, there would be ample time for the change to be effected by the survival of the best fitted in every generation. In this way every part of an animal's organization could be modified exactly as required, and in the very process of this modification the unmodified would die out, and thus the definite characters and the clear isolation of each new species would be explained. The more I thought over it the more I became convinced that I had at length found the long-sought-for law of nature that solved the problem of the origin of the species. For the next hour I thought over the deficiencies in the theories of Lamarck and of the author of the "Vestiges," and I saw that my new theory supplemented these views and obviated every important difficulty. I waited anxiously for the termination of my fit so that I might at once make notes for a paper on the subject. The same evening I did this pretty fully, and on the two succeeding evenings wrote it out carefully in order to send it to Darwin by the next post, which would leave in a day or two.

I wrote a letter to him in which I said I hoped the idea would be as new to him as it was to me, and that it would supply the missing factor to explain the origin of the species. I asked him if he thought it sufficiently important to show it to Sir Charles Lyell, who had thought so highly of my former paper.

from Alfred Russel Wallace : My Life, pp. 360-363.

Now, the new idea or principle which Darwin had arrived at twenty years before, and which occurred to me at this time, answers all these questions and solves all these difficulties, and it is because it does so, and also because it is in itself self-evident and absolutely certain, that it has been accepted by the whole scientific world as affording a true solution of the great problem of the origin of the species.

At the time in question I was suffering from a sharp attack of intermittent fever, and every day during the cold and succeeding hot fits had to lie down for several hours, during which time I had nothing to do but to think over any subjects then particularly interesting me. One day something brought to my recollection Malthus's "Principles of Population", which I had read about twelve years before. I thought of his clear exposition of "the positive checks to increase" - disease, accidents, war, and famine - which keep down the population of savage races to so much lower an average than that of more civilized peoples. It then occurred to me that these causes or their equivalents are continually acting in the case of animals also; and as animals usually breed much more rapidly than does mankind, the destruction every year from these causes must be enormous in order to keep down the numbers of each species, since they evidently do not increase regularly from year to year, as otherwise the world would long ago have been densely crowded with those that breed most quickly. Vaguely thinking over the enormous and constant destruction which this implied, it occurred to me to ask the question, Why do some die and some live? And the answer was clearly, that on the whole the best fitted live. From the effects of disease the most healthy escaped; from enemies, the strongest, the swiftest, or the most cunning; from famine, the best hunters or those with the best digestion; and so on. Then it suddenly flashed upon me that this self-acting process would necessarily improve the race, because in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain - that is, the fittest would survive. Then at once I seemed to see the whole effect of this, that when changes of land and sea, or of climate, or of food-supply, or of enemies occurred - and we know that such changes have always been taking place - and considering the amount of individual variation that my experience as a collector had shown me to exist, then it followed that all the changes necessary for the adaptation of the species to the changing conditions would be brought about; and as great changes in the environment are always slow, there would be ample time for the change to be effected by the survival of the best fitted in every generation. In this way every part of an animal's organization could be modified exactly as required, and in the very process of this modification the unmodified would die out, and thus the definite characters and the clear isolation of each new species would be explained. The more I thought over it the more I became convinced that I had at length found the long-sought-for law of nature that solved the problem of the origin of the species. For the next hour I thought over the deficiencies in the theories of Lamarck and of the author of the "Vestiges," and I saw that my new theory supplemented these views and obviated every important difficulty. I waited anxiously for the termination of my fit so that I might at once make notes for a paper on the subject. The same evening I did this pretty fully, and on the two succeeding evenings wrote it out carefully in order to send it to Darwin by the next post, which would leave in a day or two.

I wrote a letter to him in which I said I hoped the idea would be as new to him as it was to me, and that it would supply the missing factor to explain the origin of the species. I asked him if he thought it sufficiently important to show it to Sir Charles Lyell, who had thought so highly of my former paper.

It was this memoir about his own evolutionary theorising sent by Wallace to the influential expert naturalist Charles Darwin in 1858, seeking Darwin's aid in bringing its contents - if Darwin considered that Wallace's theorising was of sufficient merit - to the attention of the yet more influential Sir Charles Lyell, that prompted Darwin to make public his own theorisings about the evolution of species.

Alfred Russel Wallace had, prior to this time, been in intermittent intellectual contact with Charles Darwin - and had also supplied biological specimens to Darwin. He now decided to try interest Darwin, and through him Sir Charles Lyell, in what he thought to be the important insights, of which he expressed the hope that "the idea would be as new", that had occured to him in relation to the development of new species.

Darwin's own theorisings on evolution had largely taken their final form some fifteen years previously but he had been most hesitant about making them public largely because he thought they would prove extremely controversial; not least by inherently calling into question Biblical accounts of creation in an society that, at that time, still generally accepted Christian teachings!!!

Darwin had even prepared a 230 page abstact sketch of his theory in 1844 - but this had lain in storage under a stairway in Darwin's home in a securely sealed packet, labelled 'only to be opened in the event of my death'. Darwin had also prepared a letter asking his wife to arrange publication, with the aid of some of his scientific friends, after his death. He had also sought to make sufficient funds available for that purpose!

Darwin promply sent the manuscript he had received from Alfred Russel Wallace to Sir Charles Lyell; with his own covering letter of 18th June 1858 that included the following sentences:-

I never saw a more striking coincidence. if Wallace had my manuscript sketch written out in 1842 he could not have

made a better short abstract! Even his terms now stand as Heads of my Chapters.

Please return me the manuscript which he does not say he wishes me to publish; but I shall of course at once write & offer to send to any Journal. So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed. Though my Book, if it will ever have any value, will not be deteriorated; as all the labour consists in the application of the theory.

I hope you will approve of Wallace's sketch, that I may tell him what you say.

Several days later Darwin again wrote to Sir Charles Lyell:-

Please return me the manuscript which he does not say he wishes me to publish; but I shall of course at once write & offer to send to any Journal. So all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed. Though my Book, if it will ever have any value, will not be deteriorated; as all the labour consists in the application of the theory.

I hope you will approve of Wallace's sketch, that I may tell him what you say.

As I had not intended to publish my sketch, can I do so honourably, because Wallace has sent me an outline of

his doctrine? I would far rather burn my whole book than that he or any other man should think that I

behaved in a paltry spirit. Do you not think that that his having sent me this

sketch ties my hands? I do not in least believe that that he originated his views from anything

which I wrote to him.

In the event, Darwin, in consultation with Sir

Charles Lyell and Sir Joseph Hooker, agreed that there should be

a public joint presentation of his own and Wallace's potentially

dramatically controversial views.

Neither Wallace nor Charles Darwin were present at the historic meeting of the Linnaean Society in July 1858 when papers attributable to each were brought to the attention of the wider scientific public.

(In the form of the thirty or so persons who were gathered together on that date in Burlington House, London).

Alfred Russel Wallace was several weeks letter-delivery time away in the Moluccas and efforts were made by Darwin, Lyell and Hooker to keep him informed of developments in London in relation to his sending of his manuscript to Charles Darwin.

On October 6, 1858, Wallace wrote in a fairly magnanimous spirit to Hooker:-

My dear Sir,

I beg leave to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of July last, sent me by Mr. Darwin, & informing me of the steps you had taken with reference to a paper I had communicated to that gentleman. Allow me in the first place sincerely to thank yourself & Sir Charles Lyell for your kind offices on this occasion, & to assure you of the gratification afforded me both by the course you have pursued, & the favourable opinions of my essay which you have so kindly expressed. I cannot but consider myself a favoured party in this matter, because it has hitherto been too much the practice in cases of this sort to impute all the merit to the first discoverer of a new fact or new theory, & little or none to any other party who may, quite independently, have arrived at the same result a few years or a few hours later.

I also look upon it as a most fortunate circumstance that I had a short time ago commenced a correspondence with Mr. Darwin on the subject of "Varieties," since it has led to the earlier publication of a portion of his researches & has secured to him a claim of priority which an independent publication either by myself or some other party might have injuriously effected; - for it is evident that the time has now arrived when these and similar views will be promulgated & must be fairly discussed.

It would have caused me much pain & regret had Mr. Darwin's excess of generosity led him to make public my paper unaccompanied by his own much earlier & I doubt not much more complete views on the same subject, & I must again thank you for the course you have adopted, which while strictly just to both parties, is so favourable to myself.

Following on from Wallace's initial approach Darwin, besides

preparing a paper that was read to the Linnean Society, made

efforts to draw his notes together into a work intended for

publication. That work was prepared over a few months as, in Darwin's view, 'an abstract' of his extensive existing writings and notes. The result of these labors was published under the title

The Origin of Species in 1859.

I beg leave to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of July last, sent me by Mr. Darwin, & informing me of the steps you had taken with reference to a paper I had communicated to that gentleman. Allow me in the first place sincerely to thank yourself & Sir Charles Lyell for your kind offices on this occasion, & to assure you of the gratification afforded me both by the course you have pursued, & the favourable opinions of my essay which you have so kindly expressed. I cannot but consider myself a favoured party in this matter, because it has hitherto been too much the practice in cases of this sort to impute all the merit to the first discoverer of a new fact or new theory, & little or none to any other party who may, quite independently, have arrived at the same result a few years or a few hours later.

I also look upon it as a most fortunate circumstance that I had a short time ago commenced a correspondence with Mr. Darwin on the subject of "Varieties," since it has led to the earlier publication of a portion of his researches & has secured to him a claim of priority which an independent publication either by myself or some other party might have injuriously effected; - for it is evident that the time has now arrived when these and similar views will be promulgated & must be fairly discussed.

It would have caused me much pain & regret had Mr. Darwin's excess of generosity led him to make public my paper unaccompanied by his own much earlier & I doubt not much more complete views on the same subject, & I must again thank you for the course you have adopted, which while strictly just to both parties, is so favourable to myself.

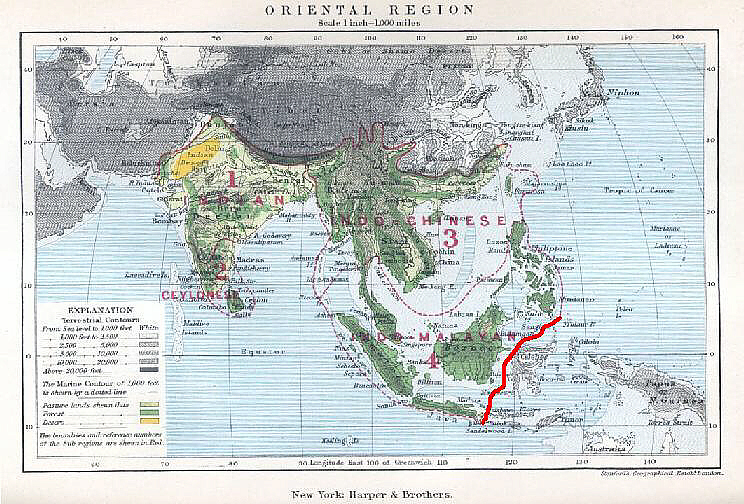

Wallace contributed greatly to the scientific foundations of zoogeography, including his proposal, based on his observations in the Malay Archipelago, for the acceptance of a marked distinction between the range offauna present in Australia and that range of fauna present in Asia.

"In this archipelago there are two distinct faunas rigidly circumscribed which differ as much as

do those of Africa and South America and more than those of Europe and North America; yet there is

nothing on the map or on the face of the islands to mark their limits. The boundary line passes between

islands closer together than others belonging to the same group. I believe the western part to be a

separated portion of continental Asia while the eastern part is a fragmentary prolongation of a former

west Pacific continent. In mammalia and birds, the distinction is marked by genera, families, and even

orders confined to one region; insects by a number of genera and little groups of peculiar species, the

families of insects having generally a very wide or universal distribution."

(From an 1858 letter from Wallace to Henry Walter Bates published in James Marchant's 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences).

(From an 1858 letter from Wallace to Henry Walter Bates published in James Marchant's 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace: Letters and Reminiscences).

In his paper "On the Zoological Geography of the Malay Archipelago" presented at a meeting of the Linnean Society in November, 1859, Wallace considered two regions similar in climatic and habitat conditions that nevertheless featured two distict complements of fauna and went so far as to suggest that:-

"Facts such as these can only be explained by a bold acceptance of vast changes in the surface of the Earth".

Some eight years later a prominent scientist named Thomas Henry Huxley coined the term " Wallace's Line "

in relation to this faunal boundary and the term has endured.

Wallace's Line is located between the Islands of Borneo and Sulawesi (Celebes) in the Malay Archipelago.

Alfred Russel Wallace' works include Malay Archipelago (1869), Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection (1870), The Geographical Distribution of Animals (1876), and Man's Place in the Universe (1903).

In 1958, (although the Linnean Society had moved away from its location of 1858, when the joint paper by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace had been presented), a memorial plaque was placed on a wall of the meeting room in the Linnean Society building.

Alfred Russel Wallace's portrait can today be found hanging alongside one of Charles Darwin in the meeting room of the Linnean Society in London. The portrait of Darwin is displayed just above this centenary plaque whilst that of Alfred Russel Wallace is displayed just above another plaque dedicated to Alfred Russel Wallace, Naturalist, Scientist, Explorer etc; and co-discoverer of Evolution by Natural Selection :-

Memorials to Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin are also to be found in close proximity within Westminster Abbey, London. This historic abbey being the venue for many high profile state occasions and also serving as something of a Pantheon for Britain's most famous Scientists, Poets, Politicians and Social Reformers.

Darwin was buried there having been given a state funeral in 1882.

This honour was not expected by Darwin's family and came about after the President of the (scientific) Royal Society in London approached the relevant church authorities saying "it would be acceptable to a very large number of our fellow-countrymen of all classes and opinions that our illustrious countryman, Mr Darwin, should be buried in Westminster Abbey".

In the event the church authorities agreed accepting that, although Darwin's works had been taken up by many to openly challenge faith, this had not been done with the consent or support of the quiet living, agnostic yet open-minded, Charles Darwin himself.

Alfred Russel Wallace was one of the pall bearers of his coffin. The other pall bearers included two dukes, the American ambassador, and Sir Joseph Hooker.

Wallace himself died in November, 1913, and in November 1915 a sculpted relief of his profile was mounted on a wall, beside a similar relief of Darwin, quite close to Darwin's actual burial place within the abbey.

The answer to this question seems to raise deep, but interesting, issues associated with Human Existence and even with the Faith versus Reason Debate itself.

It is widely known that Plato, pupil of and close friend to Socrates, accepted that Human Beings have a " Tripartite Soul " where the individual Human Psyche is composed of three aspects - Wisdom-Rationality, Spirited-Will and Appetite-Desire.

What is less widely appreciated is that such major World Faiths as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism see "Spirituality" as being relative to "Desire" and to "Wrath".

"bundles of relations and knots of roots"

tend to contribute towards giving rise to the "World" of Human Societies!!!

Although this may well depend on such things as:-

How "socio-politically doctrinaire" an individual society might be.

(Societies committed to Marxist ideology, for example, may not be particularly "Tripartite").