C. P. Snow - Rede Lecture, 1959

The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution

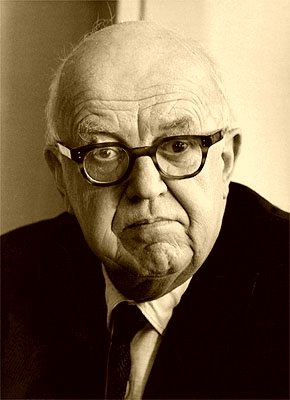

On 7th May 1959, the physicist and author C. P. Snow

( Charles Percy Snow 1905-1980 ), then fifty-three years old and a former research chemist and more recently

a top civil servant and best-selling novelist, delivered

the annual Rede Lecture in the Senate House of the University of Cambridge.

On 7th May 1959, the physicist and author C. P. Snow

( Charles Percy Snow 1905-1980 ), then fifty-three years old and a former research chemist and more recently

a top civil servant and best-selling novelist, delivered

the annual Rede Lecture in the Senate House of the University of Cambridge.Its title - "The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution" - referred to a gulf of mutual incomprehension and a mutual lack of sympathy and appreciation that Snow identified as having grown up between "literary intellectuals" on the one hand and "natural scientists" on the other.

Snow's lecture, which set out to show that this gulf between two cultures was not merely an obstacle to scientific progress but even represented a threat to the survival of western civilisation, elaborated themes he had already mentioned in the influential political magazine, New Statesman, three years earlier.

Snow suggested that western societies typically had ruling classes composed principally of humanities graduates who were effectively ill-equipped to appreciate what science had to offer. Snow identified three key menaces arising from the existence of nuclear weapons, over-population, and the gap between rich and poor nations as pressing instances of where "literary intellectuals" who in Snow's view were "natural luddites" failed to see that solutions might come from "natural scientists" who, again in Snow's view, held "the future in their bones".

In his - The Two Cultures - Snow observed that:-

"If scientists have the future in their bones, then the traditional culture responds by wishing the future did not exist".

Snow suggested there was an urgent need for the spreading of scientific innovation to poorer countries. Snow tried to make the case that the once powerful Venetian Republic, for all its accomplishment, wealth and influence nevertheless dwindled into relative obscurity dues to failures to adapt.

He compared Britain with Venice in its decadence:

"Like us, [the Venetians] had once been fabulously lucky. They had become rich, as we did, by accident…

They knew, just as clearly as we know, that the current of history had begun to flow against them. Many

of them gave their minds to working out ways to keep going. It would have meant breaking the pattern

into which they had crystallised. They were fond of the pattern, just as we are fond of ours. They never

found the will to break it."

"For the sake of the intellectual life, for the sake of this country's special danger, for the sake of the western society living precariously rich among the poor, for the sake of the poor who needn't be poor if there is intelligence in the world, it is obligatory for us and the Americans and the whole West to look at our education with fresh eyes."

"For the sake of the intellectual life, for the sake of this country's special danger, for the sake of the western society living precariously rich among the poor, for the sake of the poor who needn't be poor if there is intelligence in the world, it is obligatory for us and the Americans and the whole West to look at our education with fresh eyes."

C. P. Snow subsequently published an expanded version of his Rede Lecture The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution.

"The intellectual life of the whole of western society is increasingly being split into

two polar groups...literary intellectuals at one pole - at the other scientists, and as the most representative,

the physical scientists. Between the two a gulf of incomprehension."

"A good many times I have been present at gatherings of people who, by the standards of the traditional culture, are thought highly educated and who have with considerable gusto been expressing their incredulity at the illiteracy of scientists. Once or twice I have been provoked and have asked the company how many of them could describe the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The response was cold: it was also negative. Yet I was asking something which is about the scientific equivalent of: Have you read a work of Shakespeare's? "

"A good many times I have been present at gatherings of people who, by the standards of the traditional culture, are thought highly educated and who have with considerable gusto been expressing their incredulity at the illiteracy of scientists. Once or twice I have been provoked and have asked the company how many of them could describe the Second Law of Thermodynamics. The response was cold: it was also negative. Yet I was asking something which is about the scientific equivalent of: Have you read a work of Shakespeare's? "

In his lecture Snow said:

"So the great edifice of modern physics goes up, and the majority

of the cleverest people in the western world have about as much insight into it

as their Neolithic ancestors would have had ... As though the scientific edifice

of the physical world was not, in its intellectual depth, complexity and

articulation, the most beautiful and wonderful collective work of the mind of

man.

Yet most non-scientists have no conception of that edifice at all. Even if they want to, they can't. It is rather as though, over an immense range of intellectual experience, a whole group was tone deaf. Except that this tone-deafness doesn't come by nature, but by training, or rather the absence of training."

Yet most non-scientists have no conception of that edifice at all. Even if they want to, they can't. It is rather as though, over an immense range of intellectual experience, a whole group was tone deaf. Except that this tone-deafness doesn't come by nature, but by training, or rather the absence of training."

Initial reactions to the lecture were overwhelmingly favourable. But the real storm came three years later, in 1962, when the literary critic F. R. Leavis, a reader of English at Cambridge, ferociously attacked Snow's thesis in another high profile Cambridge lecture, the Richmond lecture, taking as his theme Two Cultures? The Significance of C. P. Snow.

Leavis described Snow as "intellectually as undistinguished as it is possible to be", adding that his lecture "exhibits an utter lack of intellectual distinction and an embarrassing vulgarity of style".

The Rede lecture, complained Leavis, showed no evidence of any scientific training or rigorous scientific habits. Nor, moreover, did Snow know anything about history. Leavis's lecture provoked an outcry.

In 1963 Snow revisited the controversy in The Two Cultures: A Second Look. Here he restated his position. Advanced western society, he said, has lost even the pretence of a common culture. Education is the means to salvation:

"Education, mainly in primary and secondary schools, but also in colleges and

universities. There is no excuse for letting another generation be as vastly

ignorant, or as devoid of understanding and sympathy, as we are ourselves."

Two - possible - recent examples

of C. P. Snow's ~ Two cultures

We each exist for but a short time, and in that time explore but a small part of the

whole universe. But humans are a curious species. We wonder, we seek answers. Living in this

vast world that is by turns kind and cruel, and gazing at the immense heavens above, people have

always asked a multitude of questions: How can we understand the world in which we find

ourselves? How does the universe behave? What is the nature of reality? Where did all this come

from? Did the universe need a creator? Most of us do not spend most of our time worrying about

these questions, but almost all of us worry about them some of the time.

Traditionally these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. Philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge. The purpose of this book is to give the answers that are suggested by recent discoveries and theoretical advances. They lead us to a new picture of the universe and our place in it that is very different from the traditional one, and different even from the picture we might have painted just a decade or two ago. …

From Stephen Hawking's - "The Grand Design" (2011)

Traditionally these are questions for philosophy, but philosophy is dead. Philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics. Scientists have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge. The purpose of this book is to give the answers that are suggested by recent discoveries and theoretical advances. They lead us to a new picture of the universe and our place in it that is very different from the traditional one, and different even from the picture we might have painted just a decade or two ago. …

From Stephen Hawking's - "The Grand Design" (2011)

Charles Darwin is my greatest scientific hero. Philosophers are fond of saying that all philosophy is a series of footnotes to Plato. I sincerely hope that is not

the case, because it doesn't say much for philosophy. A far better case could be made that all of modern biology is a series of footnotes to Darwin. And that would

be a genuine compliment to the science of biology. Every biologist treads in Darwin's footsteps and, in all humility, none of us could do better than to follow his example.

From Richard Dawkins' - "An Appetite for Wonder" (2013)

From Richard Dawkins' - "An Appetite for Wonder" (2013)

An earlier Richard Dawkins quote has some considerable relevance in relation to Snow's view of The Two Cultures:-

It has become almost a cliché to remark that nobody boasts of ignorance of

literature, but it is socially acceptable to boast ignorance of science and proudly claim incompetence in mathematics.

From Richard Dawkins' - The Richard Dimbleby Lecture: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder (1996)

From Richard Dawkins' - The Richard Dimbleby Lecture: Science, Delusion and the Appetite for Wonder (1996)

Ralph Waldo Emerson

RALPH WALDO EMERSON (1803-1882) was, in his time, the leading voice of intellectual culture in the United States. He remains widely influential to this day through his essays, lectures, poems, and philosophical writings.

In the later eighteen-twenties Ralph Waldo Emerson read, and was very significantly influenced by, a work by a French philosopher named Victor Cousin.

A key section of Cousin's work reads as follows:

"What is the business of history? What is the stuff of which it is made? Who is the personage of history? Man : evidently man and human nature.

There are many different elements in history. What are they? Evidently again, the elements of human nature. History is therefore the development of humanity,

and of humanity only; for nothing else but humanity develops itself, for nothing else than humanity is free. …

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

… Moreover, when we have all the elements, I mean all the essential elements, their mutual relations do, as it were, discover themselves. We draw from the nature of these different elements, if not all their possible relations, at least their general and fundamental relations."

Introduction to the History of Philosophy (1829)

Even before he had first read Cousin, (in 1829), Emerson had expressed views in his private Journals which suggest that he accepted that Human Nature, and Human Beings, tend to display three identifiable aspects and orientations:

Imagine hope to be removed from the human breast & see how Society will sink, how the strong bands of order & improvement will be relaxed & what a deathlike stillness would take the place of the restless energies that now move the world. The scholar will extinguish his midnight lamp, the merchant will furl his white sails & bid them seek the deep no more. The anxious patriot who stood out for his country to the last & devised in the last beleagured citadel, profound schemes for its deliverance and aggrandizement, will sheathe his sword and blot his fame. Remove hope, & the world becomes a blank and rottenness.

(Journal entry made between October and December, 1823)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

In all districts of all lands, in all the classes of communities thousands of minds are intently occupied, the merchant in his compting house, the mechanist over his plans, the statesman at his map, his treaty, & his tariff, the scholar in the skilful history & eloquence of antiquity, each stung to the quick with the desire of exalting himself to a hasty & yet unfound height above the level of his peers. Each is absorbed in the prospect of good accruing to himself but each is no less contributing to the utmost of his ability to fix & adorn human civilization. (Journal entry of December, 1824)

Our neighbours are occupied with employments of infinite diversity. Some are intent on commercial speculations; some engage warmly in political contention; some are found all day long at their books … (This dates from January - February, 1828)

The quotes from emerson are reminiscent of a line from another "leading voice of intellectual culture" - William Shakespeare.

There's neither honesty, manhood, nor good fellowship in thee.

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

William Shakespeare: Henry IV (Pt 1), Act I, Scene II

"The first glance at History convinces us that the actions of men proceed from their needs, their passions, their characters and talents; and impresses us with the belief that such needs, passions and interests are the sole spring of actions."

Georg Hegel, 1770-1831, German philosopher, The Philosophy of History (1837)

Plato, Socrates and Shakespeare endorse a 'Tripartite Soul' view of Human Nature. Platos' Republic

Understanding the Past and Present. Why is the World the way it is today?

Understanding the Past and Present. Why is the World the way it is today?

Human Being seems

to be rather "Tripartite"

It is widely known that Plato, pupil of and close friend to Socrates, accepted that Human

Beings have a " Tripartite Soul " where the individual Human Psyche is noticeably composed of three aspects -

Wisdom-Rationality, Spirited-Will and Appetite-Desire.

What is less widely appreciated is that such major World Faiths as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism see "Spirituality" as being relative to "Desire" and to "Wrath".

Could such Materialistic?, Spiritual? and Social-group? related tendencies as those "Tripartite" ones just mentioned all tend to be aspects of that 'Knot of Roots' which Emerson suggests that ~ "Man Is"

Human Societies often seem

to be rather "Tripartite"

Although there have been, and are, "Doctrinaire" forms of society organised "According to an Ideology" (e.g. Marxism), in other cases we can probably state that Human Beings are "Social Beings" and it seems actually possible that individual Human-innate "bundles of relations and knots of roots" tend to give "spontaneous" direction to the development, and continuance, of "Humanly Natural?" Societies!!!