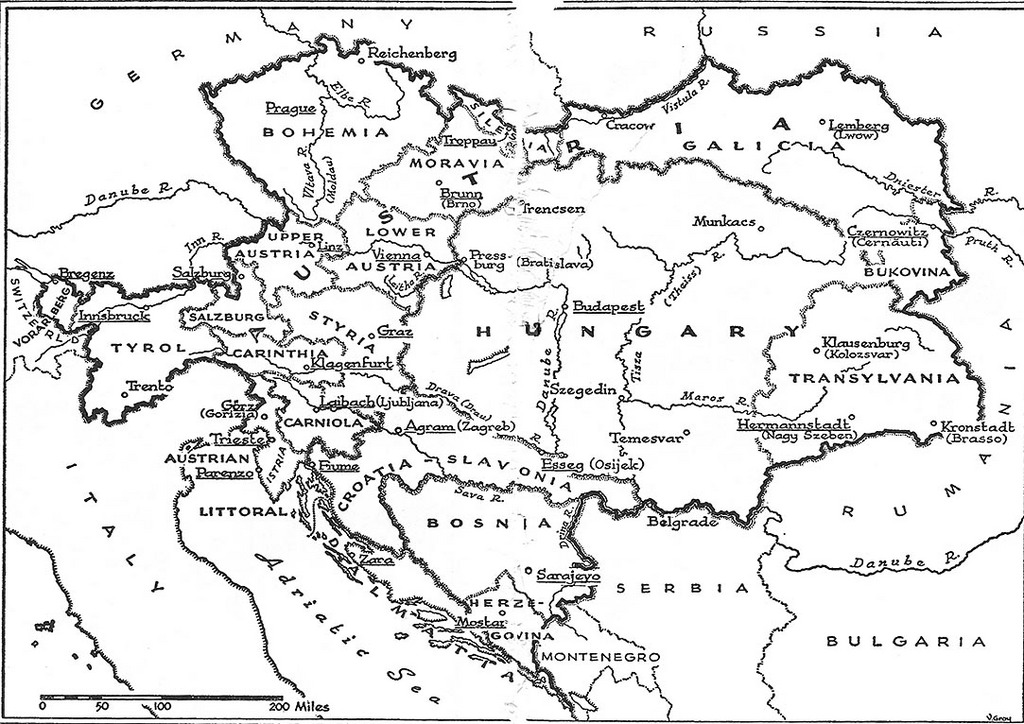

The Habsburg Empires lands and

The Revolutions of 1848

(N.B. Lombardy and Venetia in the north of the Italian peninsula were also under Habsburg sovereignty).

Map showing how the Habsburg Empire was peopled.

(N.B. Lombardy and Venetia in the north of the Italian peninsula were also under Habsburg sovereignty)

On 14 January 1848 the French authorities banned a "banquet", one of a series that had intermittently been held by 'liberal' interests after July 1847 in Paris, and subsequently widely across France, in protest at such things as limitations on the right of assembly and the narrow scope of the political franchise, with the result that the it was postponed by its organisers.

Although the banquet, now set for 22 February, was cancelled at the last minute there were some serious disturbances on the Paris streets on 22 and on 23 February which featured the building of some formidable barricades by groups of protesting citizens. The were instances of units of the civilian National Guard that had been deployed by the authorities refusing to act to contain the protest.

Faced with such unrest Louis Phillipe dismissed Guizot, his reactionary Prime Minister, who had been a particular focus of the protestors anger, on 23 February and himself, reluctantly, abdicated on 24 February.

After hearing of the developments in France, that traditional and critical source of European revolutionary impulses, Kossuth, as leader of an Hungarian opinion that had recently been impatient under the Habsburg political control, made a speech in support of a constitutionally defined separate governmental system for Hungary at a session of the Pressburg Diet of March 3.

… "From the charnel-house of the Viennese system a poison-laden atmosphere steals over us, which paralyses our nerves and bows us when we would soar.

The future of Hungary can never be secure while in the other provinces there exists a system of government in direct antagonism to every constitutional principle.

Our task it is to found a happier future on the brotherhood of all the Austrian races, and to substitute for the union enforced by bayonets and police the enduring bond of a

free constitution". …

Kossuth professed a personal loyalty to the Habsburgs and seemed to expect that the principal linkage with Austria would be that of a

personal union through the monarchy of Kings of Hungary who were simultaneously Emperors of Austria.

There was also unrest in Vienna which culminated, on 13 March, already designated as the date for the discussion of reform petitions in the Lower Austrian diet (the legislative chamber where the non-Hungarian lands of the empire held political debates), in public turmoils where several thousand university students paraded through the streets of Vienna in support of far-reaching liberalising reforms.

These students were joined by many similarly dis-satisfied citizens.

After the leaders of the students had proceeded into a government building to present their petition some of their number suspected that they had placed themselves in a situation where they could be captured by the authorities. After shouting out of windows to their friends outside they were rescued, with some damage to property, from the building.

Archduke Albrecht, a member of the imperial family, who held an high military rank, subsequently ordered the crowd to disperse, and when they did not do so, further ordered a company of soldiers to actually fire the weapons into the crowd - a number of injuries and a few fatalities occured.

Viennese citizens were alienated by this heavy handed action. The Emperor ordered a withdrawal of soldiers to certain strong points within the city. Responsibilty for the maintainance of order implicitly now fell on the Viennese Citizen Guard. It transpired, however, that the Citizen Guard tended to side with those seeking reform rather than with the authorities. By the end of the day members of the Citizen Guard had opened the doors of the Civic Arsenal and numerous weapons fell into the hands of disaffected students and citizens.

Such a series of events led to Prince Metternich, the Austrian statesmen who had done so much since the humbling of Napoleon to organise the Princes of Europe in opposition to the spirit of Revolution that had been stirring since 1789, losing the confidence of the Imperial Family and deciding to go into exile.

Although the Citizen Guard, and other citizens, attempted to impose public order there was a period where windows were broken, stores were plundered, houses were torched and factories were wrecked.

On the following day the protesting citizens demanded the the government concede the formation of a numerous National Guard composed of citzens, the abolition of censorship and the freedom of the press, the publication of the state budget, the formation of an accountable body of state ministers and the awardance of a Constitution.

The government subsequently assented to the formation of a voluneer National Guard, with a distinct Academic Legion, in the full knowledge that, in doing so, it was likely yield up Vienna to the control of forces that were likely to be composed of persons supportive of substantial reforms.

By mid-march government concessions included recognitions of freedom of speech and of the press, an acceptance that a new Diet would be convened with greater participation by the middle classes and that a Constitution would be framed - inevitably giving rise to expectations of the placing of limits on governmental power and of the offering of rights to the citizen.

A general amnesty was proclaimed to all those recent charged, or in prison because of former convictions, in relation to political offences.

The government attempted to compose a new ministry filled with notables who might be thought, by the wider populace, to have some sympathy with reform.

Habsburg ministers' attention was claimed, during these weeks, by a serious rising in northern parts of the Italian peninsula against Habsburg political control that had resulted in the Habsburg Empire's forces based there relinquishing control of a number of important cities and withdrawing to certain formidable fortresses and by developments in the German lands where the functioning of the former German Confederation, (in which the Habsburg Empire had had a notable influence), was being called into question by liberal elements favouring the emergence of some form of unified German-national state in the place of the many dynastic states and free cities of which the German Confederation was composed.

On 15 March a delegation of members of the Hungarian Diet, one hundred and fifty strong, had appeared in Vienna and had sought the awardance of a Constitution to the Empire and of a separate and independent ministry for the Kingdom of Hungary. Other Hungarian requests for but the freedom of the Press, trial by jury, equality of religion, and a system of national education were also voiced.

The principle of constitutional governance had already been conceded in the Viennese context and, after some further debate, an independent ministry for Hungary, together with the other requests, were also conceded.

In mid-March the lower gentry won out over the great landed magnates and the higher clergy and it was decided that the Hungarian Diet was to become a parliament elected under a wider, but still limited, recognition of suffrage. As March continued, and into April, there was a rush of laws passed by the Hungarian Diet in support of the administration there being free of Austrian control.

Hungary, Transylvania, and Croatia, styled as "the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen" were deemed a single state by this Hungarian Diet (without full consultation with local political opinion in Transylvania or Croatia).

Hungarian units were to separate themselves out from the pre-existing military system of the Habsburg Empire. Budapest was to be recognised as the capital of an independent Kingdom of Hungary which would frame its own budgetary and foreign policies and which was to remain associated with the other Habsburg lands only through the fact that the King of Hungary was also the Habsburg / Austrian Emperor. A titular Habsburg viceroy was envisaged as holding a role within the Hungarian constitution whilst an Hungarian minister would perform an ambassadorial role in Vienna.

The Habsburg Austrian Emperor, appearing in person at the Pressburg Diet, formally accepted these changes on 11 April.

By late March the number of newspapers circulating in Vienna had increased from three to some one hundred and many of these printed abusive attacks on notable members of Austrian society. A law for the regulation of the press of early April was openly defied by many radical elements in Vienna.

Viennese students began to show open sympathy with an overt adoption of German Nationality as opposed to an Austrian / Habsburg patriotism. The black-red-gold banner of German liberal nationalism was seen to fly, (as a result of the actions of some students), over a Viennese cathedral. The Emperor even accepted such a banner from a delegation of students and ordered it to be displayed from a window of his palace. It subsequently became commonplace for the roof-tops of private houses, and the clothing of private citizens, in Vienna, to display such emblems as symbol not only of aspirations to German unity, but also of hopes for freedom and progress.

In early April the Austrian Emperor promised in a Charter of Bohemia that there should be responsible separate political estates (assemblies) for Bohemia and for Moravia and that there would be substantial concessions to the Czech language. Czech aspiration further sought that Bohemia and Moravia with Silesia should be regarded as a single administrative unit - "the Lands of the Crown of St. Wenceslaus" - but this was not fully conceded.

A relatively liberal consitution was conceded in late April to German Austria plus Bohemia, Moravia, and Galicia promising a number of civil liberties and a two-chamber parliament where the lower house would be indirectly elected by tax-paying citizens. This satisfied many liberals in the affected parts of the Habsburg Empire but proved to be insufficient to more radical opinion - not least to the pro-reform students who continued with serious protest until, in mid May, universal manhood suffrage to a single chamber parliament was conceded.

On 25 April 1848 the Habsburg Austrian Emperor had authorised a "Pillersdorf" constitution, drawn up by Minister of the Interior Franz von Pillersdorf, applicable to Austria which envisaged its continuance as a centralised state under a politically powerful ruler. This was at odds with opinion then being popularly expressed by liberal elements.

Constitutional Developments 1

The constitution was of the "early constitutional" type, ignoring the concept of people's sovereignty. The rights held by the "sacred and inviolable" emperor held included the right

to initiate law, to sanction laws and summon the Constituent Imperial Diet (Reichstag), which was to be composed of two houses, the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies.

The Senate was to be composed of princes of the Imperial House after the age of 24, life members appointed by the emperor, and 150 members elected by large landowners.

The 383 members of the Chamber of Deputies were to be elected by the people. Both chambers were given equal rights, with bills requiring the consent of both chambers and the

sanction of the emperor, who thus retained the absolute power of veto. The immunity of members of the chambers was incorporated, like the (legal) responsibilities of the ministers.

The constitution also contained a Bill of Rights, which, however, left several delicate problems unresolved. This so-called Pillersdorf Constitution did not apply to Hungary,

which had obtained its own constitution on 11 April.

(Descriptive text taken from an official - Austrian Parliamentary - web site)

(Descriptive text taken from an official - Austrian Parliamentary - web site)

This constitution was partially intended by the Habsburg Austrian government of April, 1848, to place obstacles against the pan-Germanism it saw as potentially being embraced by many liberal Germans in Austria.

The April 25 Constitution contained a vague phrase concerning the nationality issue:-

"All the peoples of the Monarchy are guaranteed the inviolability of their nationality and language."

One of the results of further disturbances in Vienna in mid-May, (which

prompted the Emperor, and his family, to clandestinely depart from the scene whist apparently having being engaged in a routine carriage drive

departing from the summer palace, - itself located some 6 miles or 9 kilometers from the city, -

leaving behind the turbulence of Vienna for the relative security of Innsbruck),

was that the incoming political assembly (Reichstag) would have a role in the drafting of a new constitution. New electoral rules

widened the franchise and a single parlimentary chamber was authorised.

Constitutional Developments 2

Although the Pillersdorf Constitution was initially celebrated as a victory, public and publicised opinion soon criticised its enforced nature -

i.e. the fact that it had been decreed by

the emperor - increasing sharply …

…there was fierce opposition to the Pillersdorf Constitution, especially from the liberal middle classes, workers and students. This was due to the fact that the constitution was unilaterally imposed by the emperor, the aristocratic upper house was to be on an equal footing with the democratic lower house, and finally the majority of workers would have been excluded from elections …

… Following the uprising of 15 May (the so-called "Storm-Petition"), an amendment to the constitution adopted the following day expressly entrusted the Reichstag with the elaboration of a new constitution. However, the Reichstag had yet to be elected, and now consisted of only one chamber, the Senate having been dispensed with.

(Descriptive text taken from official - Austrian Parliamentary - web pages)

…there was fierce opposition to the Pillersdorf Constitution, especially from the liberal middle classes, workers and students. This was due to the fact that the constitution was unilaterally imposed by the emperor, the aristocratic upper house was to be on an equal footing with the democratic lower house, and finally the majority of workers would have been excluded from elections …

… Following the uprising of 15 May (the so-called "Storm-Petition"), an amendment to the constitution adopted the following day expressly entrusted the Reichstag with the elaboration of a new constitution. However, the Reichstag had yet to be elected, and now consisted of only one chamber, the Senate having been dispensed with.

(Descriptive text taken from official - Austrian Parliamentary - web pages)

After the departure of the imperial family their was some return to normalcy in Vienna as if the shock of such an unprecedented development caused persons of conservative and of moderate liberal opinion to question the validity of the current situation and the direction events had seemed to be taking. Soon afterwards a manifesto was published, stating that the violence and anarchy of the capital had compelled the Emperor to transfer his residence to Innsbruck; that he remained true, however, to the promises made in March and to their legitimate consequences; and that proof must be given of the return of the Viennese to their old sentiments of loyalty before he could again appear among them. Conservative opinion openly called for the Emperor's return. Radicals, more often than not, saw it as a step towards the establishment of a republican form of governance.

A critical development in the Austrian parts of the Habsburg Empire, in the form of a declared intention, issued by the government, to ensure the abolition of forced labour and of some other manorial obligations that had been imposed on the peasantry, took place in the late spring of 1848. These measures, (actually passed into law some months later - in September), were to become operative in 1849 - except in Galicia where there had been a serious rising two years previously and where these measures were to be of immediate effect. The provincial estates were charged with passing the enabling legislation in the interim.

As the news of this liberalisation spread the broad mass of the population in what was after all overwhelmingly rural areas of Austrian Empire were greatly pleased by the Emperor's promise to ensure the removal of what had been seen as burdensome obligations. Although there was to be compensation paid to the landowners by the government, and although the peasants did not immediately appreciate that taxes might impact upon them to help pay such compensation, these measures helped to maintain social peace in these rural Habsburg over several critical months.

The landowners were somewhat re-assured by the promises of compensation and had also, in any event, become themselves dis-illusioned with many aspects of the manorial system having found it increasingly limited as their estates had often tried moved away from a subsistence manorial system and towards commercial production for the market over recent decades.

From Innsbruck the emperor did not seek to immediately withdraw from his forced concessions in relation to the projected Assembly but some revulsion of feeling in conservative circles in Vienna allowed his ministers to move to attempt to dissolve perhaps the main wellspring of Viennese radicalism - the hitherto highly vocal and politically influential Academic Legion. It also happened that the University was due to close down for the long summer vacation.

The radicalised students declined to accept this disbandment, they were supported in this by the National Guard and by tens of thousands of Viennese workers. Some soldiers discharged their fire-arms at protesing citizens - in resulting turmoils that saw formidable barricades being raised in many parts of the city and composed of pavements, street furniture, trees, railings, mattresses etc.

At this point the government again yielded to the demands of the students and their allies amongst the citizens. A socio-political climate appeared in Vienna where the government accepted that it should attempt to provide employment, where landlords found themselves expected to reduce their rents and where workers sought enhanced wages together with shorter working hours. The government was faced with a fall-off in tax revenues as normal trade contracted and resorted to the mortgaging of several key assets in efforts to raise monies to fund employment schemes.

On June 26, Archduke Johann came to Vienna as the representative of the emperor but could not hope to stay to accomplish his mission because of his recent appointment to the position of "Reichsverweser" ("temporary regent") to the Frankfurt assembly. On July 8 he authorised the formation of a largely democratically-minded ministry and formally opened the Imperial Diet resulting from the agreed processes of election.

The 383 deputies, who first met on July 22, represented all of the Habsburg domains except Italy (where Lombardy and Venetia were in open rebellion) and Hungary (which had its own independent Diet). An estimated 60 percent of the deputies were classified as "bourgeois" and 25 percent "peasants," though many of these were reasonably well off. About half of the deputies (190 of 383) were Slavs of one variety or another. Despite the important role of the Viennese crowd in events leading up to the election of the Reichstag, Viennese radicals were conspicuously absent. The student-dominated Academic Legion nominated only five deputies, not all of whom proved demonstrably left wing.

In his opening speech on behalf of Emperor Ferdinand on July 22, Archduke John generously referred to the Vienna Reichstag as a constituent assembly. However, the sovereignty of the body was never agreed upon by all its members (to say nothing of the court), and its exact writ proved a subject of great controversy, particularly among national groups. Before long, distinctions between "left" and "right" soon proved secondary to national ones. Not surprisingly, all but the Germans sat according to nationality in the Reichstag.

On July 24, deputy Hans Kudlich, a law student of relatively prosperous Silesian peasant origins, put forward a proposal to abolish all feudal obligations, to which the peasantry were subject, without compensation. This proved far too radical for most of his colleagues, however, and the Reichstag spent the remainder of the summer debating no fewer than seventy-three amendments, most dealing with compensation. The formula finally agreed to at the beginning of September provided that landlords were to receive compensation for economic feudal rights - such as a stipulated share of the crop and, most importantly, the hated unpaid labor or Robot - at two-thirds of their nominal value. Half of the compensation was to be paid by peasants themselves, and the other half by the province wherein were located the lands in question. If anything, these arrangements actually improved the economic situation of the landlords. But the abolition of legal feudalism fulfilled peasants' essential demand in the revolution. Hence forth they became a stabilizing or even counterrevolutionary force, both in the Reichstag and outside it.

From the late spring when the Papacy, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and Tuscany, had signalled a retreat from support for the "Italian" challenge to Austrian authority other dramatic counterrevolutionary developments included the taking of Prague by an Austrian general Windischgratz in early June and the assertion of political control in Paris by political moderates at the expense of political radicals.

Austria also furthur regained its hold on its former sovereignty in Italy when an eighty-one year old General named Radetzky orchestrated a campaigh which defeated the Sardinia-Piedmontese troops at Custozza (July 25) and recovered Lombardy.

The Habsburg authority could perhaps take some, limited, comfort also from the fact that when representatives of several key Slavic minorities had convened in Prague in June at a so-called "Pan-Slav Congress" they had issued concluding resolutions calling for the continuance-in-being of the Habsburg Empire - (as a protective umbrella under which these Slavic peoples might hope for a degree of autonomous development)!

In late July Ministers and Deputies of the incoming "Constituent" assembly in Vienna uniting in demanding the return of the Emperor to the capital.

Eventually, in early August, the Emperor and his family, satisfied that responsible elements were once again in charge in Vienna, were prevailed upon to consent to return to Vienna and were greeted by the bulk of the population with evident welcome - the radicalised students, however, maintained a stance of opposition.

Developments within the would-be Kingdom of Hungary in these weeks included an increasing resistance being evidenced by Croats and Serbs to inclusion within an Hungarian Kingdom. The rules of suffrage envisaged for the kingdom favoured landholders, who were usually Magyar Hungarians rather than otherwise - it also became clear that Magyar Hungary was intent on promoting the Magyar Hungarian tongue as the future language of state with little concession to other languages historically spoken in the widespread lands potentially operating under the proposed system of governance to be based in Budapest.

As early as late March, 1848, important figures in the Austrian court, motivated by hopes of keeping the Austrian Empire intact, began to somewhat encourage the Croats and others in their emergent opposition to the moves towards substantial Hungarian independence then being made by Kossuth and others. Before many weeks had passed the Serbs and Rumanians similarly received support from elements within the Habsburg court as they sought to defy their own inclusion into the proposed Kingdom of Hungary (whilst professing their own loyalty to the continuance of the Habsburg Empire).

By now, however, events in Hungary rather than developments in Austria determined the course of events. The Hungarian attempt at the establishment of a largely separate statehood had run into serious trouble with several peoples, (Croats, Serbs, Slovaks, Rumanians and others), domiciled within the proposed Kingdom of Hungary each of which saw themselves as being a potentially culturally dis-regarded minority open to relentless assimilation by a domineering Hungarian state. The most obvious of these challenges being posed by the Croats led by a General Jellachic. Kossuth asked the help of first the court and then the newly elected Reichstag in curbing Croatian ambitions, but he met with refusal.

Something of a breach between the radical party and the National Guard occurred in late August after the workers actively resisted a modest reform of the work schemes with associated disturbances costing the lives of several National Guards and several tens of workers. The student radicals notably failed to go to the aid of their former worker allies and the radical press subsequently criticised the National Guards as having become instruments of reaction.

On 6 October 1848, as the troops of the Austrian Empire were preparing to leave Vienna to suppress the Hungarian Revolution, a crowd including numerous Viennese workers, university students and mutinous troops sympathetic to the Hungarian cause tried to prevent them leaving. The situation escalated into violent street battles and Count Latour, the Austrian Minister of War, was lynched by the crowd. The commander of the Vienna garrison, Count Auersperg, was obliged to evacuate the city, but he entrenched himself in a strong position outside it.

On 7 October, Emperor Ferdinand I fled with his court to Olmütz under the protection of general Windischgratz.

Two weeks later, the Austrian Parliament was moved to Kremsier.

General Windischgratz, supported by Jellachic, started an artillery bombardment of Vienna on October 26, and forces under his command took Vienna's Inner City by storm on October 31. Casualties in Vienna numbered about 2,000. Most of the concessions gained during the March Revolution were revoked.

The harsh political climate that emerged after the murder of Count Latour demonstrated the growing marginalization of the Vienna Reichstag. The bombardment and occupation of Vienna by Windischgraetz at the end of October effectively ended the urban revolutionary movement that had nourished the Reichstag since its inception.

The Imperial Diet convened in Kremsier continued in holding debates on the elaboration of a constitution during winter of 1848 / 49.

Emperor Francis Joseph I, acceded to the throne after his uncle Ferdinand I's abdication on December 2.

Neither General Windischgratz actions in Prague in June or those of General Radetzky in Lombardy in July had been fully authorised by the Habsburg authority.

The self-mobilization of the army on behalf of the dynasty meant that the power vacuum in the imperial court was ending even before Ferdinand abdicated in favor of Francis Joseph in December. For some months, it had been increasingly evident that de facto sovereignty in the monarchy lay in the crown, its ministers, and the army--and not necessarily in that order.

The decision to arrange the abdication of the relatively incapable Ferdinand I, who's aura of authority could, perhaps, been held to have been tarnished by his concessions was arrived at with the support, or the consent, of other Habsburg family members, the ministry and the army.

The Hungarian Diet, on learning of the transfer of the crown from Ferdinand to Francis Joseph, had refused to acknowledge this act as valid, on the ground that it had taken place without the consent of the Legislature, and that Francis Joseph had not been crowned King of Hungary. Ferdinand was treated as still the reigning sovereign, and the war now became, according to the Hungarian view, more than ever a war in defence of established right, inasmuch as the assailants of Hungary were not only violators of a settled constitution but agents of a usurping prince.

Such Constitutional negotiations and revisions as the Imperial Diet convened in Kremsier was giving serious attention to were almost concluded when, on March 7, 1849 the Imperial Diet was dissolved and the ill-fated Kremsier constitution cast aside by Count Stadion.

The Habsburg authority imposed a new, centralist constitution, based on the monarchic principle. The dissolution of the Imperial Diet did not give rise to any major revolutionary actions.

On the 19th of April the Hungarian Diet declared that the House of Hapsburg had forfeited its throne, and proclaimed Hungary an independent State.

Soon after the outbreak of the March Revolution the Tsar had desired to send his troops both into Prussia and into Austria as the restorers of monarchical authority. His help was declined on behalf of the King of Prussia; in Austria the project had been discussed at successive moments of danger and an arrangement had been devised whereby the Tsar's forces might enter the Habsburg Empires lands as indirect combatants - their task being to garrison certain positions still held by the Austrians, and so to set free the Emperor's troops for service in the field.

On the declaration of Hungarian independence, however, it became necessary for Francis Joseph to accept his protector's help without qualification or disguise.

An army of eighty thousand Russians marched across Galicia to assist the Austrians in grappling with an enemy before whom, when single-handed, they had succumbed. Other Russian divisions, while Austria massed its troops on the Upper Danube, entered Transylvania from the south and east, and the Magyars in the summer of 1849 found themselves compelled to defend their country against forces three times more numerous than their own.

The revolution in the Habsburg Empires lands finally ended with the capitulation in Hungary in August 1849 and Venice in September 1849.

- The European Revolutions of 1848 begin

- A broad outline of the background to the onset of the turmoils and a consideration of some of the early events in

Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Budapest and Prague.

- The French Revolution of 1848

- A particular focus on France - as the influential Austrian minister Prince Metternich, who sought to encourage the re-establishment of "Order" in the wake of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic turmoil of 1789-1815, said:-"When France sneezes Europe catches a cold".

- The "Italian" Revolution of 1848

- A "liberal" Papacy after 1846 helps allow the embers of an "Italian" national aspiration to rekindle across the Italian Peninsula.

- The Revolution of 1848 in the German Lands and central Europe

- "Germany" (prior to 1848 having been a confederation of thirty-nine individually sovereign Empires, Kingdoms, Electorates, Grand Duchies, Duchies, Principalities and Free Cities), had a movement for a single parliament in 1848 and many central European would-be "nations" attempted to promote a distinct existence for their "nationality".

- Widespread social chaos allows the re-assertion of Dynastic / Governmental Authority

- Some instances of social and political extremism allow previously pro-reform liberal elements to join conservative elements in supporting

the return of traditional authority. Such nationalities living within the Habsburg Empire as the Czechs, Croats, Slovaks, Serbs and Romanians,

find it more credible to look to the Emperor,

rather than to the democratised assemblies recently established in Vienna and in Budapest as a result of populist agitation, for the future protection

of their nationality.

The Austrian Emperor and many Kings and Dukes regain political powers. Louis Napoleon, (who later became the Emperor Napoleon III), elected as President in France offering social stability at home but ultimately follows policies productive of dramatic change in the wider European structure of states and their sovereignty.

Other Popular European History pages

at Age-of-the-Sage

The preparation of these pages was influenced to some degree by a particular "Philosophy

of History" as suggested by this quote from the famous Essay "History" by Ralph Waldo Emerson:-

There is one mind common to all individual men...

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Its genius is illustrated by the entire series of days. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. Without hurry, without rest, the human spirit goes forth from the beginning to embody every faculty, every thought, every emotion, which belongs to it in appropriate events. But the thought is always prior to the fact; all the facts of history pre-exist in the mind as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant, and the limits of nature give power to but one at a time. A man is the whole encyclopaedia of facts. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of his manifold spirit to the manifold world.

Of the works of this mind history is the record. Its genius is illustrated by the entire series of days. Man is explicable by nothing less than all his history. Without hurry, without rest, the human spirit goes forth from the beginning to embody every faculty, every thought, every emotion, which belongs to it in appropriate events. But the thought is always prior to the fact; all the facts of history pre-exist in the mind as laws. Each law in turn is made by circumstances predominant, and the limits of nature give power to but one at a time. A man is the whole encyclopaedia of facts. The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn, and Egypt, Greece, Rome, Gaul, Britain, America, lie folded already in the first man. Epoch after epoch, camp, kingdom, empire, republic, democracy, are merely the application of his manifold spirit to the manifold world.